Truth’s a Dog Must to Kennel, Battersea Arts Centre

Tuesday 28th February 2023

Has theatre’s time passed? In Tim Crouch’s latest 70-minute show, Truth’s a Dog Must to Kennel, first staged at the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh last year and now at Battersea Arts Centre (BAC) in south London, the nature of live performance is interrogated by this innovative and imaginative theatre-maker, with a little help from a virtual reality headset and William Shakespeare. Taking its title from one of the Fool’s comments in King Lear, this intriguing and entertaining event looks at how the metaphorical dog of truth has been whipped, while the hounds of post-truth deception are given too many treats.

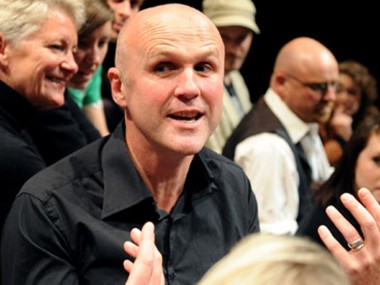

We are in the Council Chamber of BAC: it’s a big wood-panelled space with an atmosphere that evokes the old world, and this is a relaxed performance so the house lights are on, and the audience has a calm and friendly vibe. Alone on a bare stage, Crouch — who is both author and actor — uses the VR headset to describe seeing a virtual audience, pointing out ushers who are there only in a digital world, and characterising individual spectators as corporate donors, or as sitting in “this area, Delotte”. He is charming, often outright comical. At the same time he tells us that, by contrast to the huge sums paid for tickets by these people, the usher’s hourly rate is £9.75. Yes, theatre is a class thing.

The difference between this virtual audience and the real one is delightfully comic, and puts us in a good mood for the darker phases of the show, which is a great mixture of stand up, lecture and Brechtian demonstration. Crouch introduces us to a virtual production of King Lear, coming in at Act III. He’s playing the Fool, bemoans his character’s lack of good jokes and decides, in a moment of passion, to run away, to quit the production, which of course, carries on without him. This is theatre so it’s a fiction about another fiction, but his description of the play’s setting enables us, the audience, to imagine in our mind’s eye — rather like when we are reading or listening to an audio book — the scene he is describing.

By conjuring up a Shakespeare play Crouch prepares us for a sharp contrast: if theatre used to be central to our cultural experience, what is it today? His answer, an outright provocation, is that the art form is dead. “This is a funeral, isn’t it? Be honest.” Then: “No, not a funeral, this is a morgue.” Making theatre is, according to his most startling and bleakly humorous image, “like keeping our dead mum in the freezer to claim her pension”. His characterisation of theatre-making as necrophilia reminds me of a Kenneth Tynan piece from 1954 in which he attacked mainstream shows for their class-riddled complacency and called for a new theatre of anger, finishing with a battle cry: “As a critic, I had rather be a war correspondent than a necrologist.”

Crouch’s argument is that theatre as a collective experience has no place in a world increasingly free of values, a place where the individual, and the individual ego rules: “The bloated self-entitlement. The loutism. The greed.” Just like the world of King Lear, with its absurdism and its civil war. But the joke is that Crouch disproves his own theory by his practice: alone on stage he proves that theatre can work today, that it has something to say, that it can still both amuse and provoke. Using the notion that the ear is even more important than the eye, he tells an anecdote about a gross episode of a reality TV show in which family do unspeakable things to each other on stage.

The brilliant thing about this section of the show is that Crouch only uses words such as “you-know” and “you-know-what” to describe gross sexual and other bodily functions. In the minds of the audience (from audire, “to hear”) this immediately translates into images of filth, sex, sexual violence and incest — we create our individual versions, or visions, from his suggestive language. But it’s just in our individual heads. This becomes our virtual reality, and then, to give this process a historical twist, Crouch reminds us of the Dover scene of King Lear when Gloucester’s son Edgar uses words to persuade his blinded father that he is on the edge of a cliff. Intending to die, the old man jumps, but just lands in the mud.

Truth’s a Dog Must to Kennel is a play that comes from anger and despair. Crouch sees the pandemic times as an era characterized by the grim loss of life, the wrecking of families, the abuse of power, the digital encroachment of live theatre, and the decimation of the art form. His show ends with a sharp contrast between death in fiction and death in real life. But although he is visibly appalled by the lack of moral leadership in our country, the triumph of money over truth, and the continued dehumanisation of the poor, he is also able to be playful and funny — as well as passionately engaged. He is a great performer to watch.

As usual, Crouch reminds us that all representation in theatre is constructed and he enjoys showing how this is done. If he is concerned that the art form is increasingly becoming the plaything of rich elites, those who can afford high ticket prices, he expresses that it a quintessentially theatrical way, and in venues which keep prices affordable. Co-directed by Karl James and Andy Smith, helped by Pippa Murphy’s immersive sound design, all of whom are Crouch’s regular collaborators, this show both criticizes the art form, while simultaneously reinventing it. It feels like a really essential piece of contemporary culture.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk