Waiting for Godot, Theatre Royal Haymarket

Monday 23rd September 2024

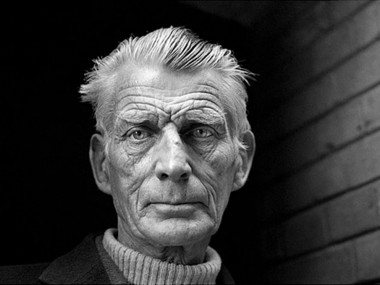

High modernism is us. Today. The incomprehensible is our reality. For the past two decades plays by Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter — which once upon a time bewildered their audiences and gave critics apoplexy — have become big West End hits. The avant-garde is now commercial. How so? By casting celebrity stars in the main roles, and emphasizing the humour. So the current revival of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot — which originally premiered in Paris in 1953 and then got a London production a couple of years later — features Ben Whishaw, a national treasure since he voiced Paddington in the film series, the third installment of which is due in November, as well as Lucian Msamati, familiar from Game of Thrones where he played Salladhor Saan.

The play, in which (according to Vivian Mercer, an early commentator in 1956) “nothing happens, twice” is disarmingly simple. Two homeless men, Vladimir (Whishaw) and Estragon (Msamati), are waiting for a meeting with Godot, who they don’t know and who never appears. Instead he sends a boy to tell them that he will come tomorrow. In the meantime, the pair are visited by Pozzo, a wealthy land owner, and his servant Lucky. As the names of the characters indicate, this story is universal, symbolic of our common humanity. In the second half, the scenario of Act One is replayed with several variations, most of which indicate that things can only get worse.

Into this deceptively simple circular structure Beckett pours the joy of physical clowning and darkly funny banter, the musings of the men about religion, their want of food, as well as a real sense of waiting being the essence of life. What are we waiting for?, you could ask, and everyone would have a different answer. This feeling of stasis, a rather serious conception of human existence, is balanced by the word play, the odd music hall routines, the prostate and fart jokes and the sheer intensity of Vladimir and Estragon’s relationship: they talk like a married couple (with nicknames Didi and Gogo). At various points they’re friends who help each other; at other times they talk about separation.

It is clear that director James Macdonald — who has a track record of staging modernist plays — favours a severe and meticulous approach to Beckett, unhurried and unstinting in its detail. Don’t expect any easy populism. On the other hand, he’s not particularly interested in the void or absence-as-presence. Instead he prefers stark naturalism. And a moderate amount of humour. What’s wonderful about his Vladimir and Estragon is that they behave like real people, not existential cyphers. Their clothes include a beanie, shabby anorak and tracksuit bottoms. You can see similar homeless people on the streets every night in London. Whishaw’s Didi is livelier than his companion, energetic and inventive as he suggests stuff to do to while away the hours, while Msamati’s Gogo is more moody. Casting a black man in this role gives his tales of being beaten up an extra layer of meaning.

The contrasting class backgrounds of Jonathan Slinger’s Pozzo and Tom Edden’s Lucky are also emphasized, with the posh Pozzo being choleric and domineering, until he loses his sight, and his servant having an expression of eternal suffering. Downtrodden. Once again, these are recognizable human beings who — like many of us — are behaving absurdly in a world that seems to have gone crazy. With the engagingly sympathetic Whishaw, who crosses his legs as he suffers bladder problems, and Msamati, doing a double act, which is by turns funny, contemplative and unsentimentally stoic, and the increasingly wild antics of Pozzo and Lucky, this feels like a fresh commentary on life today. The references to corpses piling up reminds us of current wars near and far.

Highpoints of Macdonald’s production include Lucky’s gibberish speech, which gets a round of applause, the pile up of the four characters as they collapse in Act Two, Vladimir and Estragon’s hectic hat-swapping routine, the abuse duel and an elastic belt that flies off stage. There are moments of silly “adieus” as the characters take their leave, and Whishaw sings the dog song in a perfectly hilarious way. He also indicates the audience when he says, “That bog.” At one point he is regarded as heavier than Msamati, when the reverse is obviously true. With excellently differentiated set piece speeches, such detail not only gives absurdism a human dimension, but also contributes to a high definition, superbly clear theatrical event. I have never seen this play so lucidly done.

Rae Smith’s set is a bleak chalky landscape, on which sharply drawn individuals struggle to survive after some global disaster, this “bitch of an earth” where the phrase “nothing to be done” tolls like a funeral bell. It’s the perfect setting for the four actors to demonstrate how a careful attention to detail can give the play’s episodes a variety and liveliness that I have missed in other productions. As the characters grapple with hunger and grasp after meaning, the big pessimistic themes of delusion, memory and mental collapse are beautifully contrasted with optimistic moments in which the characters come to each other’s aid. If Godot is certainly not God (a howler of a mistake), then he can stand for anything you fear, anything you expect, anything you wish for. I left the venue feeling this really is the best Godot I’ve ever seen.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk