Censorship in Malta

Sunday 15th March 2009

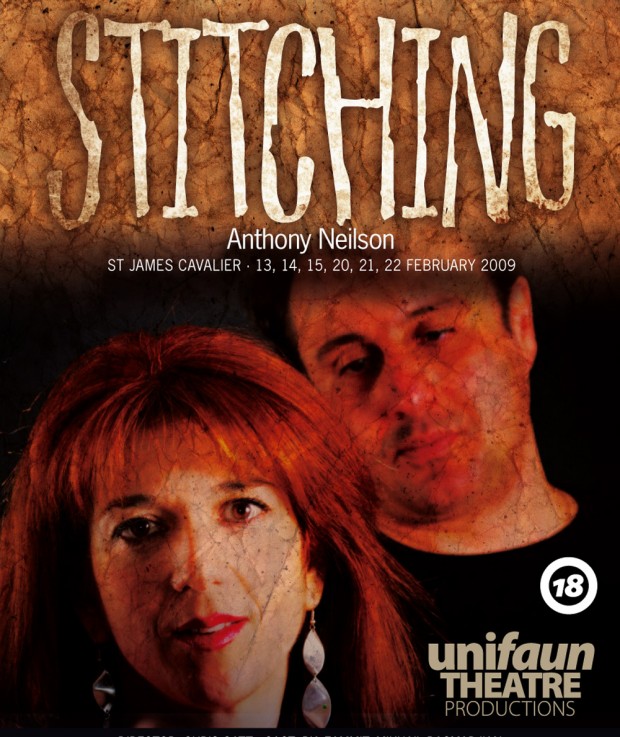

Pirate Dog has never been to Malta, but as he likes basking in the sun, I’ve always dreamed of taking him there. However, news from the island in the Med has not been good. Unifaun Theatre Company’s production of Anthony Neilson’s play Stitching has been banned (as in stopped by state power) for having dangerous references to sex in it, and because the state says it’s blasphemous. Yes, incredible, isn’t it? Amazing as this is for a European country, what’s even more distressing is the morally blinkered, artistically ignorant and flabbergastingly stupid attitude of the Maltese Minister of Education and Culture, the repressive Dolores Cristina, and local bigwigs such as Father Peter Serracino Inglott, a particularly oily member of the benighted clergy. As ever, the shepherds of culture turn out to be its most fervent abusers. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a piece, for the Sunday Times of Malta, defending the theatre and attacking the censors. Guess what? It was censored! Nice one guys. That was a really good move, and sure to shut me up! Woof, woof. The fact that Malta still has theatrical censorship is not only politically reactionary and culturally backward, but has already attracted criticism from the Council of Europe. And surely the ban on the play is a breach of fundamental rights and freedoms as outlined in the European Convention on Human Rights. Isn’t it? I can only join those who hope that Unifaun theatre’s planned legal action against the Maltese government succeeds, leading to a change in this utterly deplorable ruling.

For what it’s worth, my spiked piece reads:

It’s not often that arts news from Malta causes a stir in Britain, but the banning of Stitching, a play by Scottish playwright Anthony Neilson, has been widely publicized. For me, a London-based theatre critic and academic whose specialisation is contemporary theatre, this ban feels like a throwback to the 1950s, when the censor, the Royal smut-hound, tried to inhibit all our best playwrights.

It is true that Stitching, which was first staged in Edinburgh in 2002, is controversial and difficult: it is a play about adult themes for adult audiences. In it, a young couple struggle to overcome the stresses and strains of being in a sexual relationship. This involves questions of fidelity, past violence and the decision to have a child.

But as well as being a beautifully written play, with direct and expressive dialogues, Stitching is a thrilling experiment in theatre form. The scenes often flash forwards and backwards, and some of them are enactments of the couple’s sexual fantasies. Most revealing of all, the dialogues are brilliantly realized psychological double-binds, intricately written and excruciatingly familiar.

Like the other British playwrights that came to prominence in the 1990s, and whose work I describe in my bestselling book, In-Yer-Face Theatre (Faber, 2001), Neilson is a writer who has the courage to explore the dark side of humanity, and the imagination to create vivid stage pictures of joy as well as distress. Without doubt, Stitching is one of the best British plays of the past decade.

Having seen the play, which surely gives me an advantage over the Education and Culture Minister Dolores Cristina, I can confirm that it is a provocative and thought-provoking account of a real relationship, looking at what is best as well as worst in human beings. Her fixation on one or two lines in 50-page script is both highly selective and depressingly philistine. So the Culture Minister lacks culture, and who will educate the Education Minister?

Neilson gives his characters strong lines because they are a couple who are uninhibited about discussing how and why their love affair went wrong. Both are searching for an emotional truth that constantly eludes them; both are trying to rediscover their early sensations of love for one another. Both are frank because their feelings are still raw. The alternative is mute resentment – would that really be preferable?

True, this play is occasionally shocking but it never shocks for no reason. Every line is justified by the context of the couple’s conflicts, every confrontation pushes the story onwards. There is tenderness as well as brutality here: it is genuinely artful as well as being persuasive.

I have to say that I’m puzzled by Fr Peter Serracino Inglott’s comments. Since he hasn’t seen the play, surely he is no position to judge whether it “it relies almost exclusively on verbal exchange for its effect”. I have seen it and can assure him that it also requires the “theatrically innovatory language” which he saw as a “redeeming feature” of Blasted. In the original production, to cite just one instance, scene six was performed as a wordless grapple to the music of Iggy Pop.

Fr Peter seems unwilling to imagine how the shock delivered by a stage play might awaken a moral response, or, more profoundly, the sense of fear and pity typically engendered by tragedy. Being slippery, he quotes Aristotle, but misrepresents his gist. Isn’t it tragedy’s ability to shake our emotions precisely what Aristotle was describing? To say that the Greek philosopher was talking essentially about “enjoyment” is like saying that the Sermon on the Mount is light entertainment. (I assume I don’t have to explain the latter reference to this dolt.)

Finally, it is highly ironic that Fr Peter claims that breaking taboos is “a futile smashing-down of open doors” when the door that would enable the inhabitants of Malta to actually see the play and make up their own minds has been so effectively slammed shut by their own Culture Minister.

Both these local bigwigs are making a big mistake. The most effective way to reach a just conclusion about a play is to show it to an audience. If Cristina or Fr Peter had real faith in their ideas, they would not be afraid to allow this; since they clearly wish to ban the play, they have no faith in their own opinions. If so, why should anyone else believe them? Come on guys, trust the people.

© Aleks Sierz

1 Comment

on Wednesday 30th June 2010 at 9:41 am