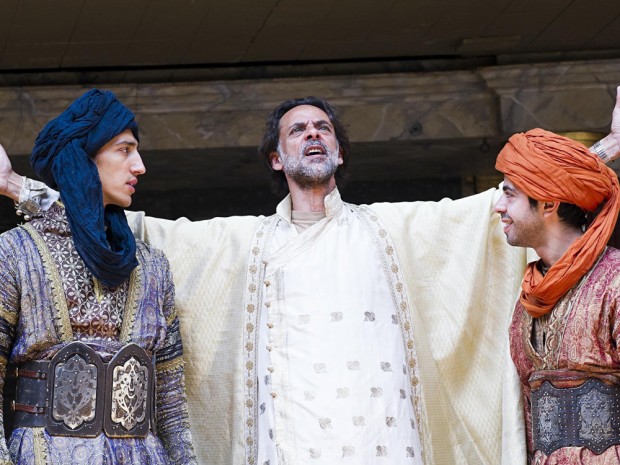

Holy Warriors, Shakespeare’s Globe

Wednesday 23rd July 2014

While it is something of a cliché to be reminded that forgetting the past is a sure way of repeating it, the problems of the Middle East are so acute that this common thought might be worth taking seriously. In Holy Warriors, playwright David Eldridge’s new look at the struggle for Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Middle Ages to the present day, the scope is ambitious and the subject matter as timely as can be. But is the play any good?

Subtitled “a fantasia on the Third Crusade and the history of violent struggle in the Holy Lands”, the play is an epic that sweeps all before it. Here is Saladin, mighty leader of the Muslims; there is Richard the Lionheart, saviour of Christendom. As the Crusades get under way in the late 12th century, it soon emerges that while Saladin holds Jerusalem, the holy city for both Christians and Muslims, Richard is unable to win it back.

In the second half, this medieval struggle between two religious cultures broadens out and covers century after century in a breathtaking extravaganza that includes Napoleon, Lawrence of Arabia, King Faisal, divers pashas, assorted Zionists, some Palestinians and Egyptians, plus the usual pack of meddling Western politicians, from the 1920s up to George W Bush and our very own Tony Blair. And some other characters that I can’t even remember. Basically, a full menu.

So, yes, it’s definitely a big meal of fantasia. We watch brief snapshots of terrible enslavements, colossal cruelties, awful privations, dreadful slaughters. And that’s only half of it. At the centre of the momentous conflict are two men: Saladin, sophisticated, strategic and sympathetic; and Richard, fearsome, frivolous and fanatical. In the background, there are various Muslim sons and assorted she-wolf royals.

When Richard finally dies and goes to purgatory, Eldridge follows and asks him the killer question: if you were to live again would you make the same choices? He then re-runs history — with the medieval characters now in contemporary combat fatigues — to see what lessons we might all learn from history. Disappointingly, these turn out to be a bit bathetic, and you leave the theatre not very much the wiser. At least, that was my experience.

Eldridge writes with great ambition and epic sweep — and the play has songs, dances and striking visual moments — and knows how to evoke modern resonances by using the names of the historic Middle East. At times, his vision of history is almost intoxicating in its splendours and heroic events. But the downside for me is a cartoonish element that runs through the show, and the fact that much is promised but little actually revealed.

Eldridge’s characterisation of the main players is never deep enough to be empathetic and moving, and his historical interpretations are never compelling enough to grab your attention. Although James Dacre’s production is lively and colourful, neither the songs nor the dancing are attractive enough to banish the thought that this view of the past is a kind of Monty Python playground, jokey and good-hearted. Holy Warriors never really stretches you.

Its cast does good work, however, with pleasing performances from Alexander Siddig as Saladin and John Hopkins as Richard; Geraldine Alexander is great as Eleanor of Aquitane and Sirine Saba impresses as Berengaria of Navarre. Yes, I know these people are a bit obscure: if nothing else, the play should send us all back to our history books. But despite the power of the idea that Jerusalem is a symbol of Middle Eastern politics, I regret to say that for me this play is not as good as it might have been.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk