Lingua Franca, Finborough Theatre

Thursday 15th July 2010

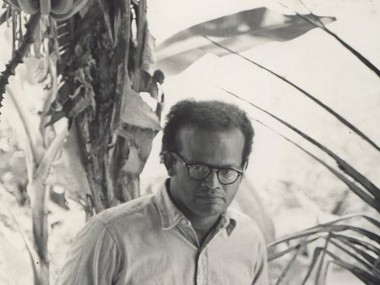

While films frequently spawn sequels and prequels, theatre — with the spectacular exception of the Bard’s history plays — tends to go for one-offs. In Peter Nichols’s new play, which opened at the tiny Finborough fringe theatre tonight, the main character is called Steven Flowers — and yes, those of you who are paying attention have by now correctly guessed that is a follow-up to Privates on Parade, Nichols’s hit play of 1977 (last revived at the Donmar in 2001). But as well as being a follow-up, how does this new play stand up on its own?

Inspired, like Privates on Parade, by Nichols’s own experiences, the story shows what happens to Steven as he comes back to Europe from doing his National Service in South-East Asia, and pitches up in Florence in 1955. His passport to the city of Renaissance masterpieces, which he has read about in EM Forster’s A Room with a View, is his employment by Lingua Franca, the local language school. And through his experiences of teaching the English lingo, he meets a handful of sharply drawn characters.

After getting a pep-talk from Gennaro, who runs the school, Steven engages with his fellow teachers: Irena, a Russian ex-pat who has seen the revolution at close hand, Jestin, an older Englishman who has never learnt Italian (or any other foreign language) but has a strong sense of idealism and grace, plus the younger women, English Peggy, Australian Madge and German Heidi. Especially Heidi, with whom he has a passionate affair.

This would not be a problem for Steven were it not for the fact that his fellow English teacher Peggy has set her cap at him (some of the humour of the play comes from these kind of colloquial phrases). Being rather repressed in the repressive 1950s, the highly strung Peggy simply can’t see that Steven has no interest in her, and is blissfully unaware that he is busy at his digs, having noisy sex with Heidi, and the plot slowly ambles to its inevitable, and rather tragic, climax. Peggy is simply not going to take rejection lying down.

Along the way to this explosive climax we get a comic account of foreign-language teaching in 1950s Italy, a good-natured and satirical view of national stereotypes — bigoted Germans, faithless Italians, vulgar Australians and dodgy Englishmen — and some coming-of-age philosophy. Interspersed with these scenes set in the staff room, there are lots of short vignettes of the characters teaching their classes, or their one-to-one pupils, and the best of these has Steven teaching English by using rugby songs and vaudeville turns. In these moments, a rather sluggish evening suddenly comes alive.

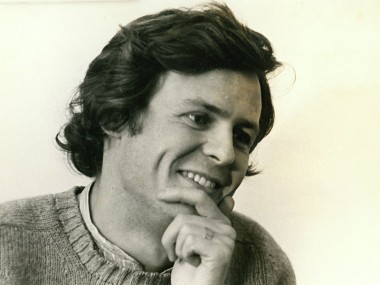

Part of the Finborough’s 30th-anniversary celebrations, the play is directed by Michael Gieleta, who has assembled an excellent cast, led by the personable Chris New as Steven. Although I had my doubts about his impersonation of playwright Joe Orton, in last year’s Prick Up Your Ears, his account of Steven as a mix of new-boy shyness and selfish determination is much more convincing. Likewise, Natalie Walter gives Heidi a glow that contrasts nicely with her anti-Semitism, while Rula Lenska adds gravitas to the Russian Irene.

Similarly, Charlotte Randle captures Peggy’s unstable edginess, Abigail McKern embodies Madge’s earthy humour and Enzo Cilenti lends Gennaro a suitably flash veneer. Theatre buffs will note that Ian Gelder, the quiet wisdom of whose Jestin acts as foil to the vividness of the other characters, created the role of Steven Flowers in the original production of Privates on Parade. So what you see on stage is a veteran actor watching a younger one playing an older version of the character he originally played some 30 years ago. Phew!

So while Nichols’s view of 1950s Italy is not entirely convincing, his account of the clash between the different nationalities in the postwar period, dominated by American culture, is both entertaining and symbolic. And while his portrait of Steven is a bit psychologically thin, his picture of Jestin adds a depth to what is mainly a comic romp. But diverting as this evening is, those with a thirst for Nichols’s anecdotes of his life would do better to turn to his autobiography, the beautifully titled Feeling You’re Behind.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk