Little Eagles, Hampstead Theatre

Thursday 21st April 2011

Space is a great subject for theatre. I’m not sure why, but it might be something to do with the contrast between the irreducible groundedness of live performance and the imaginary flights of fancy that the audience yearns to take. Whatever the reason, memorable past explorations of this subject, from the Soviet side of the space race, include Robert Lepage’s The Far Side of the Moon and David Greig’s The Cosmonaut’s Last Message to the Woman He Once Loved in the Former Soviet Union. Now Rona Munro, whose new play opened tonight, once again boldly goes deep into the history behind the first man in space.

That was Yuri Gagarin, of course, whose first orbit of the Earth happened 50 years ago. But Munro is less interested in him than in Sergei Pavlovich Korolyov, the master engineer who oversaw the Soviet Union’s early space race successes, and whose largely unknown story is a revelation. Her play is a huge historical epic that sweeps across the steppes of Russia, starting in the Kolyma gulag in 1938, where Korolyov — denounced during a Stalinist purge — has been sent as an enemy of the people. But Stalin needs engineers, and Comrade Korolyov is soon in a research facility, working on intercontinental ballistic missiles.

For reasons that are never explained, his dream is space exploration. So when Khrushchev and Brezhnev come to power after Uncle Joe’s demise, Korolyov — along with his pilots, the “little eagles” of the play’s title — gets his chance. Then, in rapid succession, Russia launches Sputnik, sends dogs into space, and in 1961 Yuri Gagarin is the first man to orbit the Earth, beating the capitalist Americans hands down. Other triumphs follow, but can the Soviets get a man on the Moon before the Americans? (No prizes for answering that one.)

Munro tells the story as a docudrama, whose historical scenes are punctuated by three contrapuntal strands: Korolyov’s relationship with a female doctor who saves his life in the gulag and reappears as a personification of his conscience; his relationship with an old man, who dies in the gulag and then haunts him as a ghost throughout his life; and finally his family life, with his wife and daughter (a very underdeveloped theme). These three strands help lift the play out of the mud of docudrama, giving it valuable injections of life every 20 minutes or so.

Because of its rather dispersed nature, Little Eagles never really focuses sharply enough on Soviet politics, except to suggest that Korolyov’s achievements took place in the context of a bitter struggle between the military and the scientists. While the generals were chiefly concerned with the arms race, the boffins were more interested in exploring the boundaries of human endurance and the possibilities of space adventure. Although the play implicitly supports the “great man” theory of history, at least, for a change, we get the Soviet point of view.

Like some of their rockets, this play is an odd construction. It is not so much a sleek, shining missile as a rather genetically challenged Russian bear of a piece, partly created through metaphors, partly from historical research, and partly from a panorama of a lost society. It is full of divagations, moments of unsettling emotion, odd encounters, unnecessary detail. Yes, it’s a mess, a three-hour-long trek in whose more tedious moments you just long for the dramaturg’s sharp scissors.

But, all right, there are some good scenes. When Khrushchev and Brezhnev first appear, the pace intensifies. When the cosmonauts wait for an inspection they compete to see who can keep their hand on a hot samovar for longest. And some speeches are verbal wonders: a guinea pig test pilot gives an amazing account of the limits of endurance; the first cosmonaut to walk in space describes the blue ball of the Earth. Some of the ariel movement is vaguely thrilling. But these highpoints are rare.

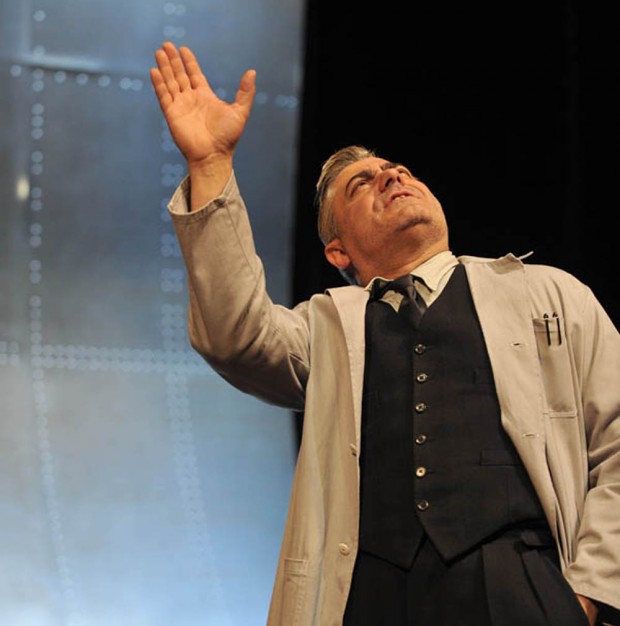

Roxana Silbert’s RSC production, designed by Ti Green, uses the same actors as the company’s Roundhouse season of King Lear, As You Like It and Antony and Cleopatra earlier this year, and sparks fitfully but never really takes off. The Russian ambiance is generally unconvincing, the accents of the peasants are risible, and some of the gulag acting is silly. Yet all is forgiven when Darrell D’Silva begins to warm to the role of Korolyov, embracing the passions of this genius with wholehearted conviction. Likewise, there is good work from Brian Doherty as the bluff and vulgar Khrushchev, Greg Hicks as a menacing general and the ghost, Noma Dumezweni as the doctor and Dyfan Dwyfor as Gagarin. But even they cannot save this maddening, curious, sometimes inspiring, often informative and yet deeply frustrating play.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk