Tactical Questioning, Tricycle Theatre

Monday 6th June 2011

Verbatim theatre has been the flavour of political theatre for the past two decades, and no theatre has done more to promote this style of public witnessing than the Tricycle in Kilburn, north London. Its artistic director, Nicolas Kent, has created a special style of verbatim drama called tribunal theatre, where the results of long-running public inquiries or trials are edited into an evening’s viewing. His latest venture, Tactical Questioning: Scenes from the Baha Mousa Inquiry, which opened tonight, illustrates the pros and cons of this type of infotainment.

First the facts: at the Haitham hotel in Basra, southern Iraq, Baha Mousa — a 26-year-old receptionist — and nine others were arrested on 14 September 2003 by the British Army as suspected insurgents. About 36 hours later, Mousa was dead. A postmortem examination of his body showed that he had been asphyxiated, and there were signs of 93 injuries. Five years later, a public inquiry was held into his death and the treatment of the other detainees.

Tactical Questioning is a compressed account of part of that inquiry. Gerard Elias QC, counsel to the inquiry, asks a series of soldiers and their superior officers what happened to the Iraqi men who were arrested in 2003. The result is ghastly: they were held in squalid conditions, with no toilets; their clothing was torn off; they were hooded; then starved and dehydrated; then made to adopt stress positions for hours on end; they were denied sleep; they were yelled at, and they were repeatedly beaten up. Their injuries are stomach-turning.

Although these practices have been illegal in the British Army since they were abandoned in the early 1970s in the fight against the IRA, they were used extensively in Iraq. Worse than that, these forms of torture are given a sickening name: “Tactical Questioning”. The middle of the play is taken up by the testimony of Corporal Donald Payne, a repulsive bully who was accused by courts martial of inhumane treatment of prisoners and, unusually, found guilty. His words are evasive, unrepentant and his account of Mousa’s death almost unendurable.

But if Payne is vile, his superior officers are scarcely more impressive. Clearly, they knew about these dreadful practices, but did nothing. One of them uses the chilling words: “I followed orders.” Others — such as Major Michael Peebles — simply looked the other way. Nor are the politicians any better: Alan Ingram, the Armed Forces minister at the time, comes across as slimy, deliberately unhelpful and utterly unscrupulous. Only Lt Col Nicholas Mercer — the army legal adviser — seems to have had any real concerns, and at least he acted on them.

As with many other accounts of the Iraq War, watching all this is a bit depressing. You’d have to be very naive to be shocked at the actions of these young soldiers, who obviously lacked training and leadership. Like any army, they are a society in miniature: brutal working-class soldiers led by upper-class toffs. As ever, the lessons learnt from setting an amoral army loose on a civilian population were absorbed too slowly and too late.

But Tactical Questioning also has its limitations. It is edited by Guardian journalist Richard Norton-Taylor, who makes a big deal about its truth. In a blog, he explains that his play “contextualises” the official report, which is “expected very soon”. In other words, although this play is based on reality, it is pre-empting the actual report of the inquiry, by a former appeal court judge, Sir William Gage. And this is a high-risk strategy. The last time that the Tricycle did this, with Justifying War, its play about the Hutton Inquiry, the play’s conclusions were completely at odds with those of the inquiry report. Surely verbatim theatre should prefer truth to fiction…

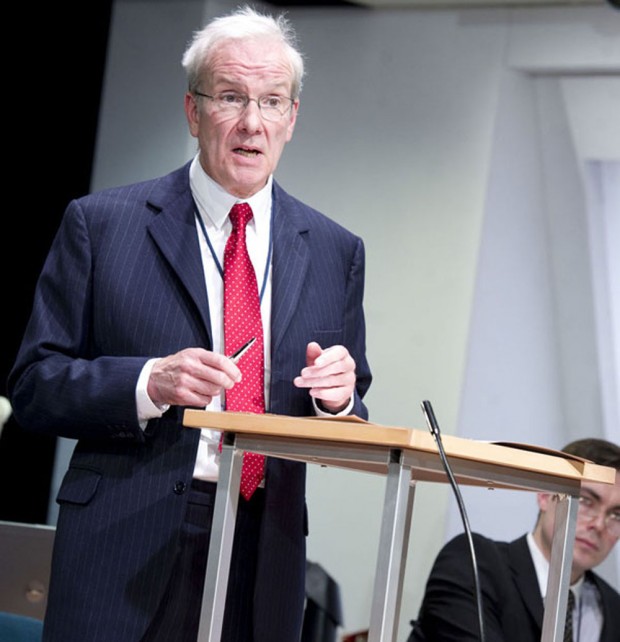

The other limitation of tribunal theatre is an aesthetic one. Visually, this is a play that is stuck in a courtroom peopled by men in suits and furnished with bog-standard office equipment: a desert of desks, computer screens, video links, box files, camera images and painfully ugly wooden fittings. Polly Sullivan’s realistic design reproduces this banality perfectly. More seriously, at the end of the evening we know much more about army brutality than about the chief victim, Mousa. There is no attempt to tell us who he was, or what he did in his short life. The production has a gaping hole at its centre.

Nicolas Kent directs with simplicity and clarity. His cast are excellent. Thomas Wheatley, a veteran of no less than seven other tribunal plays, is the cross-examining Elias, and his version of tactical questioning — polite, meticulous and relentless — absorbs a lot of our attention. As Payne, Dean Ashton is frighteningly believable, while David Michaels’s Mercer is as impressive as Simon Rouse’s Ingram is unpleasant. The acting is so real that when the actors swot away a stray fly, they do it in character. All in all, the sense of bearing witness to the unmasking of an injustice makes for a powerful, if uncomfortable, night at the theatre.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk