Closer, Donmar Warehouse

Monday 23rd February 2015

Political sleaze, arguments over Europe and fears for the NHS — sometimes it feels as if it’s the 1990s all over again. And, right on cue, theatre has been staging a whole shelfload of revivals of work from that decade: Kevin Elyot’s My Night with Reg, Conor McPherson’s The Weir and Jonathan Harvey’s Beautiful Thing. Not to mention a West End outing for Jez Butterworth’s Mojo. The Donmar Warehouse, under the spirited leadership of Josie Rourke, has led this trend, and its latest offering is Closer, Patrick Marber’s brilliant 1997 sexual tragi-comedy, revived now with Rufus Sewell in the cast.

Set in London, and partly a Valentine to the hidden nooks and crannies of the metropolis, the play tells the story of two couples – Dan and Alice, and Larry and Anna – who meet, fall in love, cheat, split up and then fall in love all over again with each other’s partners. The story starts in a hospital, where obituaries journalist Dan has brought Alice, a streetwise waif and sometime stripper, after she’s been knocked down by a cab. They fall for each other. Eighteen months later, Dan has written a novel based on Alice’s life and is having his photograph taken by Anna. He falls for her. But then so does Larry, a doctor from the first scene of the play. The permutations then play out over the course of the evening.

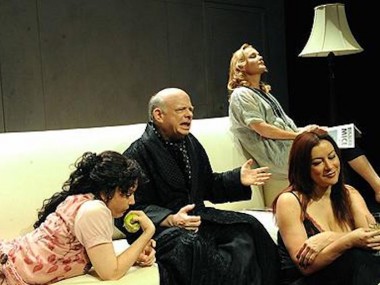

At first, I thought that David Leveaux’s revival was miscast. Compared to the first production, Rufus Sewell’s Larry is too subtle to be convincing as the caveman that the role demands; Rachel Redford’s Alice is more comfortable being vulnerable than being enraged; while Nancy Carroll’s Anna lacks sensuality and Oliver Chris’s Dan is not reserved enough. Somehow the chemistry felt all wrong. But, thank goodness, things warmed up in the second half and the set pieces – in the strip club, in Larry’s office and the “mercy fuck” scene – do catch fire.

Closer is elegantly structured, with its four characters never appearing all together on stage, and most scenes being two-way dialogues – one a hilarious sex chat on the internet – while the play has a formal balance which encourages comparisons with Noël Coward’s Private Lives. Marber’s writing retains its freshness and there are many memorable lines: Alice’s “Everyone loves a big fat lie” or Larry’s “I love your scar, I love everything about you that hurts” or Anna’s “You’re a man, you’d come if the tooth fairy winked at you”. (This last one always gets more laughs from women than from men – I wonder why?)

This is punchy writing which, given its author’s experience in penning scripts for television comedies such as Alan Partridge, is always in a hurry to get to the punchline. Every emotional exchange ends with a verbal bang. Very seductive, but also rather irritating. So although the dialogue is snappy, funny, explicit and occasionally moving, what you miss is a sense of compassion, the quality of pity. Yes, this is a young man’s play, with both the faults as well as the qualities that that implies.

Still, Marber’s account of the tensions of love is compelling and asks the right questions: why do men carry more emotional baggage than women? And why are women always ready – at any cost – to rescue them? And why do they all lie to each other, only to confess afterwards? At the same time, Marber shows how telling the truth can sometimes can be just as hurtful as telling a lie. Other issues, such as personal and sexual identity, come at you with their shirts undone. There is enough guilt, hurt and self-loathing here to last you a lifetime.

With its title borrowed from Joy Division’s second album, Closer is a hip event, and Leveaux’s production can boast a neon-soaked design by Bunny Christie and good music from Fergus O’Hare. Although the acting is uneven, Sewell is most convincing when he is most raffish and Carroll lights up in her exchanges with him. At their best, Chris is a boyish Dan and Redford a fragile, needy Alice. If the play no longer carries the crackling electric charge of the new, it still remains a powerful anatomy of the sex war.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk