Broken Glass, Vaudeville Theatre

Monday 19th September 2011

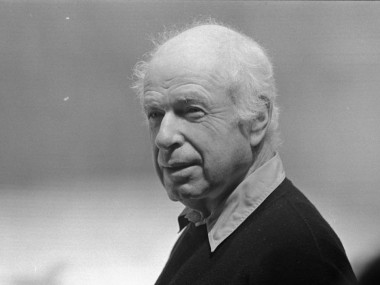

Arthur Miller is one of those geniuses whose plays are metaphor-rich even when their storytelling is slow. First staged in 1994, Broken Glass is surely his best late-period drama, and this revival, directed by Iqbal Khan, arrives in the West End after originally opening at the Tricycle Theatre last year. This time, the ever-watchable Tara Fitzgerald joins Antony Sher in the cast.

Set in Brooklyn in 1938, the play is like a case history from a cabinet in Sigmund Freud’s practice. A middle-aged woman, Sylvia Gellburg, suffers from a sudden and mysterious paralysis of her legs. She is confined to a wheelchair. Is her condition a result of her identification with the suffering of the Jews in Nazi Germany, and especially a reaction to the violence of Kristallnacht (referred to in the play’s title), or is it due to a growing fear of Philip, her husband, and his own self-loathing? Sylvia’s case is taken on by Dr Harry Hyman, a doctor who must have missed the ethics class during his training because soon he is openly attracted to his patient. He makes a sharp contrast to Philip. Whereas Philip tries to hide his Jewishness, Harry isn’t bothered; while Philip is impotent, Harry is a bit of a ladies man. In fact, so much so that his wife Margaret has to keep a keen eye on him.

Miller writes with heartfelt sincerity, and his picture of Jewish life in 1930s New York is fascinating. Each of the characters, and especially Philip and Sylvia, experience the twin pressures of anti-Semitism (real or imagined) and assimilation (successful or fantasy). Miller shows how the sense of a person’s identity can be affected by events many miles away, and how the 1930s were a time of emergency. He also indicates that we all inherit humanity’s problems as well as its joys. Yet here the road of regret leads to redemption.

There’s plenty of dramatic irony when the Philip character seeks to ingratiate himself with his boss, a WASP, and in the horrifying and climactic moment when he reveals his fear of anti-Semitism quite unnecessarily. In seeking to assimilate, he ignores the fact that few people deign to shake his hand. Such humiliations are then passed onto his wife. Only Harry’s sound good sense can effect a dramatic cure. It is a fiction after all.

Khan’s production has an ugly set by Mike Britton, all peeling sickly green walls and unattractive wooden furniture. But his actors shine — up to a point. Sher’s Philip is excellent, especially his grotesque contortions and the scene when he collapses is played with such intense grace that it vividly etches itself on the retina. By contrast, Fitzgerald’s Sylvia beautifully suggests the strength that the sick and vulnerable sometimes possess. As her doctor, Stanley Townsend is a towering bull of a man, oozing sexual power and arguing with passionate intensity. He is well matched by his wife, played with bubbly charm by Caroline Loncq. Given that these performances are so good, why didn’t the evening take off?

The first reason must be that all the actors struggled with their Brooklyn accents, and so much energy went into this that it took a good hour before the performances really settled down. The second reason is that Khan’s directing concentrates on creating perfectly balanced stage pictures, and these lack dynamism, giving an overall impression of inertness. A piece where an onstage cello player, Laura Moody, thrillingly conveys the frayed nerves and jangling emotions of the characters deserves a much more fluid production. Of course, Miller’s play is strong enough to survive, but — a bit like Philip’s condition — it’s an unnecessary struggle.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk, 19 September 2011