Farewell to the Theatre, Hampstead Theatre

Wednesday 7th March 2012

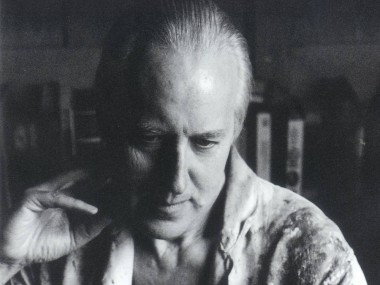

Harley Granville Barker is hardly a household name, but he was a huge influence on British theatre today. During the Edwardian era, he promoted new writing at the Royal Court; he wrote plays such as The Voysey Inheritance, Waste and The Madras House, which have been successfully revived; he invented the modern idea of the director; he advocated permanent companies of actors; and he campaigned for a national theatre. Not a bad legacy. Now he is the subject of a new play, which opened tonight, by American penman Richard Nelson.

Born in 1877, Granville Barker enjoyed great success as a playwright, actor and manager before suffering a mid-life crisis during the first world war. At that time, he asked his first wife, the actress and producer Lillah McCarthy, for a divorce and deepened his relationship with Helen Huntingdon, an American novelist who eventually inherited a huge amount of money. Nelson’s play is set in Massachusetts in April 1916, where a world-weary, impoverished and 39-year-old Harley is sitting out the war and scouting for work. Not only has Harley quit the London stage, but he is still smarting from the disappointment of the failure of his plans for a national theatre, which were dropped when war was declared. Holed up in a boarding house, he waits to hear from his wife about the divorce and wonders whether he should abandon theatre for good. This is also the year in which he writes his own Farewell to the Theatre.

Yet, as Nelson’s play shows, Granville Barker is surrounded by all things theatrical. There is an English actor, Beatrice Hale, who is the niece of the actor Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson, and is having an affair with a young American student, Charles Massinger. They are staying with ex-pats Dorothy, who manages the boarding house and whose brother Henry is a professor at a local college. Other Brits include George, Henry and Dorothy’s cousin, and Frank Spraight, the great Dickens recitalist, who is also visiting.

As in the mature work of Chekhov, some of these people are marking time, while others — especially the American Charles — are advancing their careers. It emerges that Henry, the brother of the boarding house manager, is locked in a horrible and humiliating offstage grapple with Weston, a professor who specialises in Shakespeare. So Henry’s production of Twelfth Night, in which Charles plays a minor part and Harley attends as a distinguished guest, becomes a ferocious battleground.

While Harley waits to hear from his wife, his friend Frank — in the evening’s most moving subplot — is also waiting for news from his wife, who is dangerously ill. This character beautifully embodies the emotional restraint of the Edwardian male. Meanwhile, Harley and Beatrice share their matrimonial unhappiness in a relationship that is intriguing and touching, but never gets enough air to breathe. Likewise, Harley’s disillusionment is lightly outlined, and the play’s brevity means that the audience has a lot of dots to join up.

Harley’s depression and frustration are clear: his most often used line is “I don’t know what I want.” But by keeping the character of Helen, his new lover, offstage, Nelson removes the chance of seeing his emotional life in action. Instead of that, we get glimpses of the essential generosity and fairness of the man in his dealings with the other characters, and with their illusions about what the theatrical life entails. While we hear a bit about Harley’s ideas about the necessity of simplicity in directing, and there is inevitably a speech about the importance of theatre to life, the main impression is that the vicious rivalries of the academic world, which Harley is tempted to join as a way of earning a living as a lecturer, are more of an issue than the world of footlights and make-up. Sadly, too much of the play’s action happens offstage, too many of the relationships are obscure and the play is too short to really resonate with the present.

Roger Michell’s controlled and empathetic production unfolds on Hildegard Bechtler’s gloomy set, and is mainly played in the failing light of a depressing night. What rescues the evening are the excellent performances, with Ben Chaplin as the fastidious and occasionally reptilian Harley and Tara Fitzgerald as the highly strung and nervy Beatrice. Jason Watkins is a fine Frank and Jemma Redgrave is an attractive and truth-speaking Dorothy. William French makes his professional debut as Charles. Although the production values exemplify Harley’s vision of ensemble playing and truth to life, Nelson’s play lacks the dramatic punch needed to make us really care.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk