The Witness, Royal Court

Monday 11th June 2012

A powerful trend in contemporary theatre is the family play. But the families usually depicted tend to be of the standard two-point-five variety, while other more complex forms — families as they actually are — tend to be ignored. So initially the good thing about Vivienne Franzmann’s new play is that it focuses on a family where the child is adopted. More controversially, it is about a white man who adopts a black girl from Africa.

The story takes place in today’s Hampstead, but has roots in the past. Joseph is a news photographer whose images of war and atrocity are world famous. Since the death of his wife, he lives alone and takes snaps of local weddings. Now, his adopted daughter Alex is home after her first year at Cambridge University. She was rescued by him when he was covering the Rwandan genocide, and is curious about her past: as a baby, she was pictured in one of his iconic, prize-winning photos. At first, the old white Dad and his young black daughter share a powerful bond. They bicker and laugh; they share the grief of loss; it looks like a great relationship. But when she hears that a major retrospective of his work is on the cards, her curiosity about the African wars leads her to explore her past, and to gradually discover a dreadful secret. Central to this revelation is Simon, the witness of the play’s title. Who is he, and what does he know?

On one level, this is a powerful play about individual identity. Alex is a young woman who has worked hard as a teenager and now can enjoy her life at uni, yet her self-confidence is barely skin deep. Although she loves her Dad, she gradually realises that she doesn’t really know who she is. At the same time, this is a story about images, whether of atrocity or of celebrities, and how they dominate our view of the world. It is a tale filled with references to pop culture, the star and the image.

But how does it feel, Franzmann asks, to be the person behind an evocative or shocking photograph? For while pictures record a single moment, a person’s life is made up of many moments, and what we think we know about the past can sometimes be completely reversed. In The Witness, there is also a clash between the experience of the Hampstead English and that of the Rwandan survivors. As in Drew Pautz’s Love the Sinner, both Alex and Simon take on the mantel of the accusing African.

One of the joys of the play is the character of Joseph, a ragged, unrestrained and out-of-control man who is on the verge of losing everything. But, despite evoking this character, Franzmann’s playwriting lacks character and her storytelling, while perfectly efficient, is occasionally clichéd and often predictable. Soon after the initial exposition, the story slackens and Joseph’s exposure and decline sadly refuse to defy our expectations.

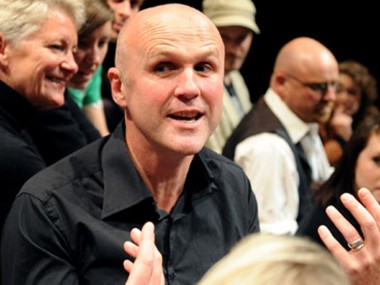

Simon Godwin’s well-paced production unfolds on Lizzie Clachan’s immersive set, which — perhaps unnecessarily — turns the whole of the Royal Court’s small Theatre Upstairs into Joseph’s Hampstead home, a place of chaise longues, comfy armchairs and Turkish carpets. Here, Danny Webb’s passionate and grizzled Joseph contrasts nicely with Pippa Bennett-Warner’s perky but vulnerable Alex, while David Ajala’s Simon is dignified and sincere. Despite good performances, and a story which occasionally vividly reminds us of half-forgotten genocides, and is on the right side in its advocacy of integrity and truth, this play is never quite dramatic enough to repay our interest.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk