Antigone, National Theatre

Wednesday 30th May 2012

Although some contemporary plays — notably Posh and 13 — have accurately taken the temperature of the times, what about the timeless classics? Does Sophocles’s Antigone (dated about 441BC) have anything to say to us today? How can it be of our time too? As the National Theatre wheels out this play, with a cast led by Christopher Eccleston and Jodie Whittaker, onto its main stage, such questions hang in the air like the smoke from an ancient funeral pyre.

The third of the Theban plays, Antigone is a perfect tragedy: everyone behaves in the right way, but with fatal results. It’s a true tragedy of irreconcilables. Creon, the ruler of Thebes, has decided that Polynices, who has died fighting his own brother in a civil war, has no right to be buried. Instead, his body must be left on the field of battle, a prey to scavenging dogs. On pain of death. This antagonises the dead man’s sisters, Antigone and Ismene. At the start of the play, they meet secretly. Antigone wants to bury her brother — it’s a sacred duty — but Ismene is afraid that Creon will put them to death if they do. Antigone decides to do the right thing anyway, thus bringing on her head the sentence of being entombed in a cave while still alive. Despite the warnings of the blind prophet Teiresias, Creon doesn’t relent, with disastrous consequences which also involve Haemon, Creon’s son and Antigone’s betrothed.

To get the full psychological and emotional impact of the situation, it helps to know that Antigone is also Creon’s niece, that Creon is Jocasta’s brother, and that Antigone, Ismene and Polynices are all the children of Oedipus. Yes, it’s a terrible tangle. What a family. But this is also a tale of moral duty, and — despite the title — more about Creon, who does the right thing and still gets stuffed, than about his niece.

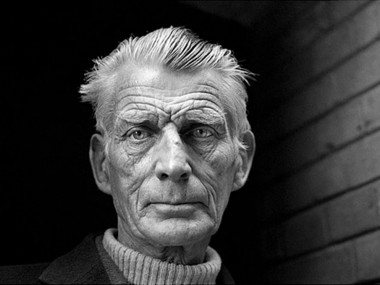

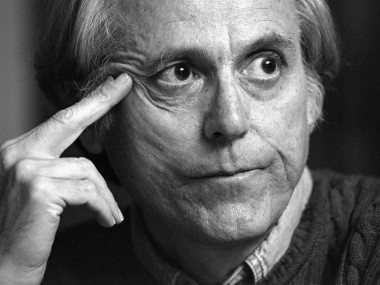

Polly Findlay’s version starts off like a political thriller. The setting suggests the former Eastern bloc, a surveillance state which acts with the force of psychological repression, as well as suggesting other evil regimes from all over the world. It’s a bunker, a war room or a dictator’s nuclear-proof hideaway. The powerful design, by Soutra Gilmour, is hard in its concrete brutalism, implying a nasty West Wing, a dark episode of 24. But although this production begins with an image that recalls the way that Obama and Clinton watched the killing of Bin Laden, the sense of the contemporary is hard to sustain. After all, this is a play about gods and fates. Christopher Eccleston understands this perfectly, dominating the stage by balancing the different public faces required of a politician, yet also convincing as a family man and an individual struggling with belief. He also cynically plays the terrorist card.

Much less satisfying is Jodie Whittaker’s Antigone. From the start her speeches feel oddly thin, lacking body, weak in words. When she tells her uncle to kill her, her gesture suggests a casual shrug rather than noble self-sacrifice. Yet, despite this, her preparation for execution is gruesomely moving. Both the main leads get solid support from Annabel Scholey (Ismene), Luke Newberry (Haemon) and Jamie Ballard as a gnarled and deformed Teiresias.

In this production the lines of the chorus are split among a host of individual actors, who become a pack of political advisors, security experts, report writers, spin doctors, military experts, secretaries and functionaries. This works really well, and the ensemble holds the play together while propelling the action forward. I was less impressed by Don Taylor’s translation, originally written for television, which awkwardly mixes the slangy and the stately. Why didn’t the National commission a fresher version? After all, this approach worked well for Richard Bean’s One Man, Two Guvnors.

So while Findlay’s production looks and feels great, with its pulsing music, haunting electrical storm and general atmosphere of fear, its contemporary flavour is diffused by including too many different historical associations, and never quite getting over the archaic qualities of the text. I really wish she’d gone the whole hog, and completely updated it. After all, Martin Crimp showed how this could be done effectively in his 2004 Cruel and Tender, a truly contemporary version of The Women of Trachis (also by Sophocles). As it is, Eccleston rules okay in most of Antigone’s scenes, Whittaker disappoints, but the play finally fails to say anything definite about the world today.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk