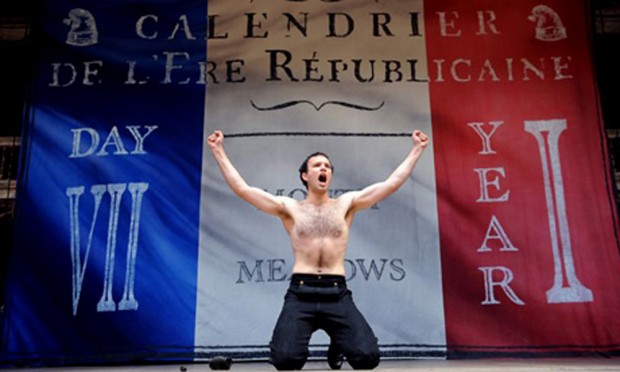

Liberty, Shakespeare’s Globe

Wednesday 3rd September 2008

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. The verdict of Charles Dickens on the French Revolution neatly sums up the two sides of this tumultuous period in history, when the battle-cry of “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” echoed from thousands of passionately idealistic throats, many of which eventually fell victim to the Reign of Terror they themselves had helped to create. Liberty, a new play by Glyn Maxwell, is a stage adaptation of Anatole France’s 1912 novel Les Dieux ont soif (The Gods Are Thirsty).

Set in Year One of the revolution (1793 to you and me), it tells the story of a young artist, Evariste Gamelin, a youthful idealist who becomes a People’s Magistrate, and an increasingly radical supporter of the Incorruptible Maximillian Robespierre. Because of this, he falls out with his best friend, Philippe Demay, who is also Gamelin’s rival for the sexual favours of Elodie, a young embroiderer. Another woman, the actress Rose, is added for balance, and an older couple, Maurice, an aristocrat turned puppeteer, and Louise, the well-connected fixer, round out the picture.

The conflict is familiar: all the excitement of a youthful time when everything was made anew (including the calendar, whose renamed months hang at the back of the Globe’s suitably spartan staging) clashes with the scepticism of worldy experience. As the reality dawns of a terrorised population, with thugs in charge, so the best spirits either become fanatics (Gamelin) or cynics (Philippe). Maxwell’s play reruns these classic arguments, with terror being excused by the political crisis, as France is threatened with invasion and conspiracy.

But the use of Danton’s Law, which justified emergency powers, once again appears as a form of corruption, with ideals being destroyed through an obsession with Virtue. Gamelin tries to be purer than pure; he tries to be the self-denying New Man of the Revolution — but only succeeds in being inhuman. Much of the cost is born by Elodie, his wife, whose flirtacious and vivacious spirit is first turned into a lifeless parroting of slogans, and then into a nervous breakdown as the Terror finally knocks on her door.

Anatole France’s humanistic point of view triumphs over the excesses of show trials and mass murders. Having eaten its children, the Revolution is survived by those who never really believed in it anyway. The slightly off-putting cynicism of this conclusion is not the play’s only message, and Maxwell highlights those moments when Gamelin does some good, and shows how his conscience is troubled when the desire to help change society runs up against the realities of arbitrary power. After all, is not cynicism as destructive a point of view as political fanaticism? Perhaps the most appealing middle way is embodied in Maurice, who constantly questions the clichés of the new order.

Liberty is an engaging enough piece that, in Guy Retallack’s solid production on Ti Green’s colourful sets, rehearses the debate about the limits of arbitrary power in a way that carries some uncomfortable resonances. You can’t help thinking that when governments use an atmosphere of fear, not to say terror, to curtail civil liberties, it’s ordinary citizens that are the main losers. Retallack’s cast, led by David Sturzaker as the monstrously virtuous Gamlein and Ellie Piercy as the pert then possessed Elodie, are in fine voice, with John Bett’s Maurice particularly impressive as the declamatory voice of reason. Although this could hardly be described as a revelatory evening, it is a good show about a subject — political change and arbitrary power — that somehow refuses to go away. Aren’t we also living in the best and worst of times?

© Aleks Sierz