Stevie, Hampstead Theatre

Wednesday 25th March 2015

Some poets turn out to be one-hit wonders. Who today remembers any other poem by Stevie Smith that doesn’t end with the line “Not waving but drowning”? And what’s the point of writing a biographical play about a writer who kept herself to herself and whose life seems thoroughly uneventful? Hugh Whitemore, in his 1977 piece, which was originally put on in the West End with Glenda Jackson in the title role, avoids these questions with a swerve. Here is Stevie, he says, take her or leave her.

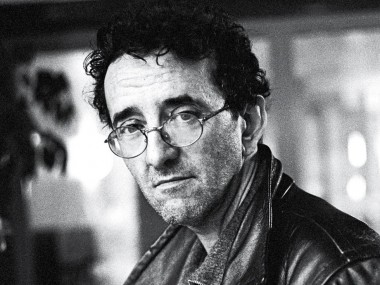

Of course, by casting Zoë Wanamaker as the poet in this solid revival, Hampstead Theatre is offering its faithful audiences the opportunity to see this star live. But the play is quite demanding. Whitemore has made a career out of biographical plays that are basically interlocking monologues. You know the kind of thing: tell, don’t show. If you close your eyes you could be listening to the radio. So don’t expect much onstage action.

Elegantly organised in two parts, with Act One taking place in the 1950s and Act Two in the 1960s, the action — such as it is — takes place in the sitting room of Stevie’s home in Palmers Green in north London. Born in 1902, Stevie — the nickname was the result of a childhood jibe — lives with her “lion aunt” in suburbia, and commutes to central London, where she works as a secretary at Newnes Publishing Company for 20 years from 1923. Although she is very affectionate with her aunt, other emotional closeness is not for her; after she has sex with Freddie, her fiancé, she breaks off her engagement to him: “I don’t feel up to being a good wife.”

The main theme of her life is death. Her mother died when she was a teenager, and she considered suicide several times before attempting it in 1953, which results in her early retirement. In her comparative seclusion, she develops her poetic gift, gets published and then finds herself drawn into the bohemian literary scene of the capital. Although she keeps saying that she is exhausted, especially by the demands of social life, she constantly finds images and words to describe her unique and quirky take on the world.

Whitemore’s play is subtly constructed, but also pretty old hat. Although Wanamaker is joined on stage by Lynda Baron as her aunt, and Chris Larkin as Man, who plays a handful of the men in her life, the evening is fatally static. This kind of literary theatre is pretty deadly, although Wanamaker — as you’d expect — is constantly watchable, being humorous and precise, her often plaintive voice often being jaunty as well as suddenly depressed. Her keynote is a kind of desolate gaity, which is both appealing and a bit sad.

Stevie died of a brain tumour in 1971 which, with a truly ghastly irony, deprived her of words. Christopher Morahan’s workmanlike revival is easy to watch, easy to sympathise with, and easy to fall asleep in. But that is the fault of the play. Simon Higlett’s set is beautifully meticulous, but what you remember is Wanamker’s careful recreation of this deeply eccentric person who is both playful and cutting. But it’s hard to forget the lack of drama, and the lack of action is a definite flaw. It is an evening of lacks.

© Aleks Sierz