Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Donmar Warehouse

Thursday 17th December 2015

The world of 18th-century European aristocrats is a place of fantasy. Think Jean-Honore Fragonard, think Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, think Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, author of the 1782 masterpiece, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, an epistolary novel whose pages conjure up the smell of burnt incense and snuffed candles, and evoke rich frocks and rumpled sheets, bon mots and double entendres. It pulses with the spirit of libertine desire and the nasty joys of forceful seduction, betrayal and revenge. And Christopher Hampton’s 1985 adaptation is more faithful to the original than its characters are to their various lovers.

However sophisticated, the lives of Choderlos de Laclos’s personages teeter not only on the brink of disillusion and dissolution, but also of history. While they disport themselves, the French Revolution, and Madame Guillotine, is fast approaching. This is reflected in Tom Scutt’s superb set, where at first the rich and elaborate furnishings are covered with dust sheets, while candles are lit and glittering crystal chandeliers are pulled up to the ceiling. But behind the elaborate decoration you can see the slats and crumbling plaster of the rooms in which the drama takes place. Yes, a whole society is on a precipice.

But the story’s main protagonists are unaware of the world beyond their salons and boudoirs. Experienced lovers La Marquise de Merteuil (Janet McTeer) and Le Vicomte de Valmont (Dominic West) are old amours whose main delight now is the corruption of innocents, and revenge against their bêtes noires. She challenges him to seduce the convent-educated, virginal and naive 15-year-old Cécile. But although Valmont rises to this task, his own preference is for Madame de Tourvel, the religious-minded, prudish and loyal wife of a provincial magistrate. Although these seductions are successful, they result in many tears, and both Merteuil and Valmont rekindle not only their attraction to each other, but also receive an unexpected coup from Cupid’s arrow.

Hampton’s adaptation captures the cool grace of the original, and the cynical and calculated conversation of the very rich and very idle. Its charm lies in its acidic mix of joy in intrigue and deception, along with an erotic thrill in the postponement of desire. For these gens décadent the extremes of pleasure depend on the effect they have on other people, usually more narrow-minded or more moralistic than themselves. Amid all the frolics, the larger themes of power, trust and betrayal come at you déshabillé, while memorable phrases fall from the lips of all involved.

Just as the bodies of the aristocrats are hidden from view by elaborate costume, so the messier sides of desire — the sweats, emissions and stains of sex — are concealed beneath beautifully honed and witty phrases. But this secret place of physical contact twitches like a subtext beneath all the verbal exchanges. In this sex war, power — the ability to make other people do your bidding — is more arousing than flesh. And revenge is a demonstration of pouvoir.

At the same time, there is an undertow of sadness, of loss, as the libertines realise that, despite all of their experiences and adventures, they feel mainly an emotional aridity, a despair. Years pass, and they are no happier. And the women are at a distinct disadvantage. “Women are obliged to be more skilful than men,” comments Merteuil about the sexual double standard. The more vulnerable they are, the crueller their fate. While Hampton’s version spares us the final humiliation of Merteuil, it also reminds us that the seduction of innocents is partly a sexist fantasy.

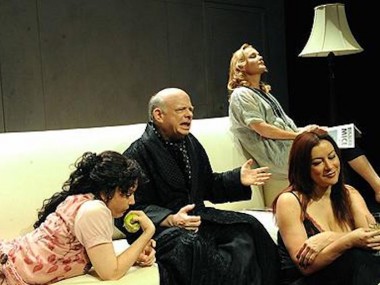

Josie Rourke’s visually enchanting production holds up for our inspection a good selection of cunning vixens competing with clever bad boys. But sadly not all of the acting is as good as the cast list suggests. West’s Valmont is unconvincing, and he turns in an erratic performance that reminds you that although he has a strong stage presence, he simply lacks charisma. McTeer’s poised and serpent-like Merteuil, with her glaring and pained eyes, is much better, and so are the other women: Elaine Cassidy’s fragile Tourvel (whose breakdown is shocking) and Morfydd Clark’s naive Cécile. In a production that is colourblind, Una Stubbs and Adjoa Andoh play the older generation while Jennifer Saayeng and Edward Holcroft are the other youngsters. In the end, it is the strength of the story, and Hampton’s writing, that propels the evening forward, despite some lacklustre acting from West.

© Aleks Sierz