Battlefield, Young Vic

Friday 5th February 2016

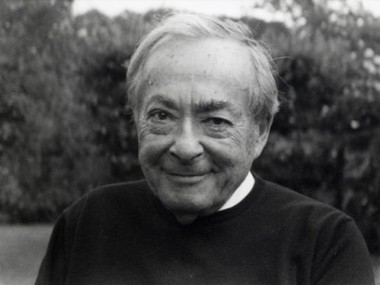

Legendary director Peter Brook makes theatre that teaches audiences to be human. Now 90 years old, he brings his latest project to London from Paris, where he has been based at the Bouffes du Nord since quitting the UK more than 40 years ago. Called Battlefield, it is a 65-minute distillation of part of his 1985 11-hour epic, The Mahabharata, and revisits the ancient Sanskrit myth of the Kurukshetra War, and the struggle between the two warring families of the Kauravas and the Pandavas.

Co-created with his long-term collaborators Jean-Claude Carrière and Marie-Hélène Estienne, Battlefield is set in the aftermath of the great battle — which according to the myth lasts 18 days, and has left millions of bodies lying on the ground — so the evening begins with a vivid description of this carnage. As one of the survivors says, “Victory is a defeat.” The victor of the monumental slaughter, Yudishtira, the new Pandava king, is left with the question of how to make sense of the senselessness of war.

As Yudishtira (Jared McNeill) seeks out the old blind king, Dritarashtra (Sean O’Callaghan), he also takes council from the queen Kunti (Carole Karemera) and a handful of other sages (Ery Nzaramba). What makes this complicated ancient family saga accessible is the parables and stories told as these tormented kings search for the way and the light. I particularly liked the wry humour of the fable of the worm crossing the road, and the story of the snake who attempts to wriggle out of responsibility for biting a child to death.

On a bare platform stage, beautifully lit by Philippe Vialatte, the sun-baked ochres and orange tints glow while the four-strong cast are dressed in black, with red and orange scarves. A mild feeling of summer heat radiates from the set, while Toshi Tsuchitori’s drumming — at one point sublime — punctuates the story. All the actors move with an impressively controlled stillness of being, confident and smooth as if in the grip of a kind of perfection that you rarely see in London. They speak with a gently majestic rolling delivery that gives this tale a Shakespearean dimension, and the text has the simple limpid quality of ancient parable or fable. Here the stage is a place of melody, aural, visual and textual.

Amid the stillness, there are some memorable moments, as when a bunched cloth is turned into a baby, which floats Moses-like on the river (in this case the Ganges rather than the Nile), or when a snake is tied up and releases itself, or when a woman utters the most piercing cries you have ever heard. At the same time, it’s hard to be unaware that we are being taught a lesson in religious philosophy, that behind the beauty stands Brook, and he is telling us, with his typically cool perfectionism, that to be human means to relinquish all earthly goods, and concerns, to strip ourselves bare in front of the eternity of spirit.

But although the contemporary resonances of a show about the aftermath of bloody war are immediately apparent, the message of acceptance and resignation is a bit hard to stomach. Are we really supposed to accept, to take one instant example, that the plight of Syrian refugees is just another example of the wheel of fortune and to relinquish any agony that we, or they, might feel? Yet without such contemporary echoes Battlefield is just an exercise in Orientalism, a way in which a comfortably middle-class audience appreciates the ancient wisdom of India and pats itself on its back, saying, how interesting, how broadminded we are, how exotic. And then do nothing. Is this really the best way to be human?

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk