The Caretaker, Old Vic

Monday 11th April 2016

The new age of austerity demands entertainment. And I mean demands. The age of austerity doesn’t just creep into the room, cosy up to you, and then whisper a mild request into your ear. Oh no: the age of austerity crashes through the door, overturns a table and then jumps onto a chair. From this height, it wags its bloated finger in your face and lays down the law: thou shalt have comedy. And the main casualties of this new edict are the old modernist masters: Beckett, Genet and Pinter. And latest in a line of muggings is The Caretaker.

First staged in 1960, the play is one of Harold Pinter’s three comedies of menace, works which mix naturalism with moments of acute absurdity, everyday life with strong symbolism, until an air of unease and distress begins to radiate off the stage. In the past, such work was often cursed with an excess of seriousness, and could sometimes be condemned to limp ponderously across the boards. Today, it is more likely to be infected with an abundance of gaiety, with waves of laughter flattening out the pieces’ complexity.

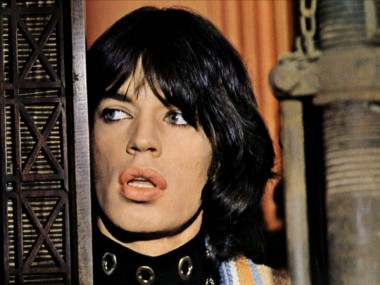

So how does Matthew Warchus’s revival shape up? Early signs, I must confess, are not good. But then this is a production aimed not at greyhairs, but at youngsters. As the set trundles down the stage, the eerie gothic music suggests a Tim Burton movie, or maybe even Goosebumps. Then Aston, a troubled young man played by Daniel Mays (fresh from a cameo in the BBC’s Line of Duty), arrives along with Davies, an angry tramp with wild hair played by an almost unrecognisable Timothy Spall (Peter Pettigrew in Harry Potter). After witnessing a scuffle in a café, Aston has offered the homeless Davies a bed. But this kind act annoys his brother Mick, an aggressive bully played by George MacKay (Private Peaceful).

The spiky interactions between the three men, and the power games they all play, create an evening of tense and frustrating encounters. This time I was struck by how relevant the story remains: three needy men, all of whom have been psychologically damaged. Davies has the rat-like cunning of the trained survivor, but he has clearly been the victim of some kind of mental collapse (his circular thinking, his lies and his repetitions show just how disturbed he is). And his paranoid fears, and his obsession with his papers, have a wider resonance in a Europe currently being criss-crossed by migrants.

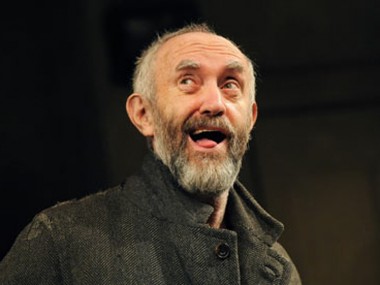

But Aston and Mick are scarcely any healthier. Aston, as he tells us in an elaborate set piece (sitting on his bed with the lighting fading in the background until he is the only lit part of the stage), has had electro-convulsive therapy and his fantasies of being able to build a garden shed far outstretch his actual abilities. His brother Mick, with his bullying and senseless aggression, likewise comes from the same family which has scarred both of them. This is a drama in which damaged psyches jostle each other around the space. At first, Spall’s Davies mumbles, and his words are almost incomprehensible; when you tune in, the music of his speech becomes stronger, although I never sensed the danger at the heart of the character. Mays’s Aston is more serious, and his limping, needy persona comes across clearly, movingly. By contrast with his slowness, MacKay’s Mick is more manic, and his speedy rendition of some of the longer speeches results in a sound salad, in which the words once again get lost. You get the feeling, but not the content.

As designed by Rob Howell, the decayed one-room set is full of junk, not in the picturesque tradition of Steptoe & Son, but rather just the detritus of useless consumption: broken appliances, dirty furniture and squalid decorations. Warchus’s production has some good moments: when Spall’s Davies slips on a velvet smoking jacket he turns immediately into a pipe-toting man of the world, a suggestion that within the tramp lurks a canny chameleon ready to adapt to any situation. I was much less keen on the spacey cinematic music, and the elaborate scene changes, while the inclusion of two intervals, which results in a running time of three hours, felt excessive and self-indulgent. Playing Pinter mainly for eccentricity and laughs is occasionally fun, but what gets lost is the essential Pinteresque quality of the writing. And that just makes me sad.

© Aleks Sierz