Faith Healer, Donmar Warehouse

Tuesday 28th June 2016

Oh dear. I could have sworn I had a book about Irish playwright Brian Friel somewhere. But I can’t find it. Or maybe I never bought it. Maybe I just thought I might have bought it. Maybe it’s a false memory. Better ask my wife. Now at least I’m in the zone, that place called ambiguity that is, aptly enough, one of the characteristics of Friel’s 1979 play, Faith Healer, which is being revived with a starry cast at this boutique venue. With its themes of miracle cures, bitter exile and fallible memory, this tale is as resonant as ever. Suddenly it feels like the ideal post-Brexit play.

Frank Hardy is an Irishman who travels around the remote villages of Scotland and Wales in a battered van, offering miracle cures to the chronically sick. As this faith healer realises, in the first of the play’s four monologues, he has “a unique and awesome gift” which occasionally actually works. But he is also beset by doubts: is he, after all, just a con man? Are his infrequent successes just chance — or is he the unknowing servant of a mysterious higher power?

Frank’s monologue is interrupted by two other monologues, one by Grace, his wife, and the other by the Cockney Teddy, his manager. As they tell the story it slowly emerges that the most significant events of the past few years have been domestic rather than religious: the deaths of Frank’s mother and his child. But, in this study in ambiguity, there is also uncertainty: have these deaths actually happened? Who knows? Then, at the play’s climax, Frank returns to Balleybeg in Donegal, a fictional place that Friel has explored in most of his work. Here Frank’s gift for healing finally betrays him, and this homecoming returns to the spiritual, with the sacrifice of the scapegoat.

The strength of the play is that each of the monologues tells a different story. In his own eyes, Frank is troubled and noble; in his wife’s version, he is much more down to earth and fallible; and Teddy’s account is even more revealing. Which of these should we believe — all, or none of them? Friel implicitly argues that memory is uncertain, that words — which can soothe through incantation and ritual — cannot be trusted to convey the truth, and, finally, that home is as destructive as exile. Faith Healer is also a strong metaphor for theatre: Frank is an actor, a performer who relies on the uncertainties of inspiration, and Friel understands that his gift as a playwright is just as temporary, mysterious and treacherous as Frank’s for healing. The play is deeply mysterious and mysteriously deep.

At its centre are the complex relationships between the two men and one woman. The various shades of love and hate, attraction and resentment, present a tremendous challenge to any director and their actors. Lyndsey Turner’s production has a stillness that invites a theatrical miracle, and a design by Es Devlin that evokes both the endless rain that plagues touring performers and the lonely domesticity of the main characters, at least one of whom is addressing us from beyond the grave.

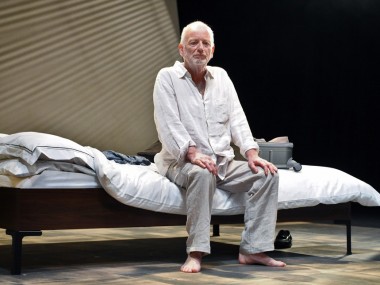

Stephen Dillane lends Frank a quiet charisma, with his easy charm barely disguising his self-doubt. His characteristic gestures are the hand in the jacket and the confident smirk of the maverick showman. Gina McKee has an attractive openness and subdued brightness that contrasts with Dillane’s darkness, but her stiff shoulders powerfully suggest the suppression of pain. As Teddy, Ron Cook exudes the impresario’s confidence, and is of course as great a performer as his client. But his ready repartee barely conceals his desperation, which he can only control with drink. This revival is verbally hypnotic, emotionally intense and compellingly ambiguous: it is also haunting and leaves an indelible impression. Plays rarely tell us so directly what it feels like to be human — this one does. And then some.

© Aleks Sierz