Human Animals, Royal Court

Monday 23rd May 2016

As I sit down to write this, a crow is cawing outside my window while night falls; for an awkard moment I think it might be a raven, and this reminds me of Edgar Allan Poe. Is the black bird saying “Nevermore”? And why should that worry me? Well, I’ve just seen Stef Smith’s resonant and disturbing new play, Human Animals, and it’s made me particularly sensitive to all of the creatures with which we share our urban spaces. And of all the possibilities that this co-existence might spawn.

The play begins with some observations of small changes, nothing to get anxious about. One young couple, Jamie and Lisa, find a dead pigeon on their living room carpet; middle-aged John and his widowed neighbour Nancy discuss the flocking of some 90 birds in his garden. Then Nancy’s daughter Alex returns from a gap year and is told by her mother not to go out into the back garden — not until “environmental control” has made sure there aren’t any foxes in the shrubbery. And John meets a man, Si, in his local pub, who seems to have some secrets of his own.

Hush, is that a mouse in my kitchen? I go down and have a look, but can’t find anything. So anyway: this dystopic scenario, in which nature begins to spill over, in which animals start to swarm, is reminiscent not only of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, but also of Caryl Churchill’s Far Away, and more recently of her Escaped Alone. What distinguishes Smith’s version is her appealing mix of bizarre humour and acute discomfort. It’s genuinely creepy to think of birdlife out of control, of insects breeding all over the place, and big and small mammals nibbling at our limbs while we sleep. This vision of an ecological disaster is uncomfortably close to the bone.

Each character in the 75-minute play reacts differently to the ever-deepening emergency. As road blocks are put up, Si is angry because he can’t get across the city to visit his young daughter who lives with his estranged wife. John and Nancy put up with the new regulations which impose a curfew and ration goods with a stoic spirit vaguely reminiscent of the Blitz, while — after Jamie gives up his job in a call centre — Lisa goes to work for Si, and witnesses firsthand the strains of an organisation struggling to cope with a national catastrophe. Meanwhile, Alex joins some local protestors who are trying to protect a park from being cleansed of all wildlife by fire, and Jamie begins to actively protect as many animals as he can hide in his shed.

Smith’s writing includes choral sections… sorry, I have to break off because I think I just I heard a fox screaming in the back, but maybe it’s just a cat. Where was I? Oh yes, choral sections which widen out our horizons and give the play an epic scope and a poetic feel. The metaphors certainly have resonance: Human Animals reminds us that migrants are often characterised as swarming or pouring across Europe, while the use of key words like “incineration” suggest the Holocaust, and ethnic cleansing. Smith shows how gradually a national emergency can develop, and how ordinary people can accept extraordinary situations. And while she shows how fear of infection can be used to spread panic and obedience in a population, she is also emotionally attuned to the power of resistance.

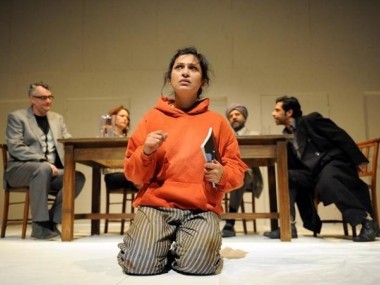

Hamish Pirie’s production is decidedly chilling, and enjoyably so. Camilla Clarke’s open and versatile set, with its huge windows that are splattered with blood as birds fly into them, features sick avians, shadowy figures in hazard suits and creepy insects in perspex boxes. Lights flash, strobes pulse and flames roar up. From above falls ash, and the action feels dangerous and immersive. But there is also a firm strand of humour that Pirie brings out well. We laugh in the face of disaster.

The speed of the storytelling and the fluidity of the production pose challenges for the actors, and not every exchange is as grounded and convincing as it could be. Still, there is good work from Lisa McGrillis and Ashley Zhangazha as Lisa and Jamie, Ian Gelder and Stella Gonet as John and Nancy, and Natalie Dew and Sargon Yelda as the slightly underwritten Alex and Si. Back in 1970, Robert Taber began his book The War of the Flea (an account of guerrilla warfare) with a quote from a harassed US officer: “We had to destroy the town in order to save it.” These evocative words could be the epigraph of this superbly written, wildly imaginative and thought-provoking play.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk