Shopping and F***ing, Lyric Hammersmith

Wednesday 12th October 2016

Playwright Mark Ravenhill’s 1996 Royal Court debut was not the decade’s most shocking piece of theatre, but its title was, and is, certainly the most annoying for producers and publicists. Under a Victorian law — the Indecent Advertisements Act 1889, amended by the Indecent Displays (Control) Act 1981 — the word “fuck” is banned from public display. Originally drafted to stamp out explicit adverts by prostitutes in shop windows, the law is still used to ban adverts for a piece of fiction. Apparently that word is just too shocking to be seen in the public realm. Hence the asterisk-fest of this play’s title; hence also the tube adverts where the second word is given as a blank box, an obvious invitation to theatrical graffiti scribblers. By contrast, in the safety of the theatre’s premises, the ushers can shamelessly wear screaming Shopping and Fucking T-shirts.

This 20th-anniversary revival — all glorious flash, videos and music — works hard to distract us from the fact that the play is an old-fashioned flat-share drama featuring a group of friends, all of whom have been named after members of the 1990s Cool Brit boy band Take That. So there’s the idealistic stoner Robbie, the junkie Mark and the ever-enterprising Lulu. The plot shows how, in a series of rapid scenes, their attempts at self-improvement come under threat. Mark books into a clinic to cure his addiction, but is thrown out. On the streets, he finds Gary, a teenage rentboy. Meanwhile, Lulu’s attempt to get a job involves stripping off for middle-aged Brian, who tests her by giving her a bag of Ecstasy to sell. Cue dance scenes. And then some telephone sex. The story climaxes when Mark brings the damaged and self-destructive Gary home to meet Lulu and Robbie.

But as well as being a slice of everyday life, Shopping and Fucking is also an urban fairy tale that, in this version at least, glows with its own youthful idealism, and matches every in-yer-face atrocity with a more mellow response. As well as being full of speeches about the big themes of globalisation, consumer capitalism and conflict resolution, it is an exquisite blank fiction. If this sample of Generation X is passionate about anything, it is storytelling: at one point, Robbie tells Gary about the death of grand narratives; at another, Lulu compares supermarket ready-meals with globalisation and Empire. Mark spouts psychobabble while Brian lectures the youngsters on the theme of “Money is civilisation”. At the same time, the atmosphere is soaked in sexual ambiguity, queerness and psychological damage.

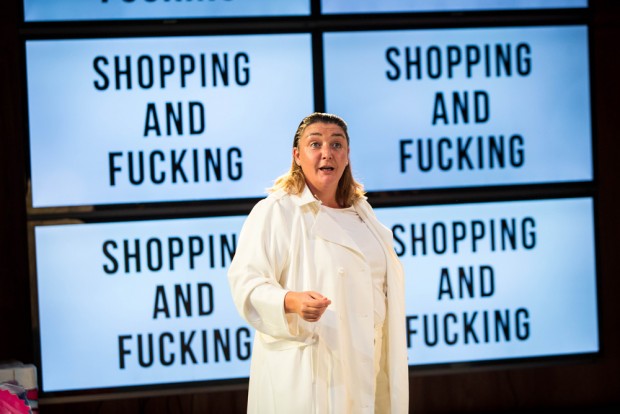

Sean Holmes’s revival immediately restores the gender balance by casting Ashley McGuire, who played Falstaff at the Donmar in 2014, as Brian, and Jon Bausor and Tal Rosner’s constantly morphing set is supplemented with video effects and pulsing techno music (curated by Nick Manning). The bright young cast — Alex Arnold (Robbie), Sam Spruell (Mark), David Moorst (Gary) and Sophie Wu (Lulu) — bring a vigorous openness to their roles, but the production style is cartoon comic book. Everyone is acting as if they’re on drugs: speedy movements, coke confidence, tripped out gestures, ecstasy dancing and spliffing comedowns. The colours are vivid, and the message is perhaps a bit too clear: each item of clothing and each piece of furniture has a price tag.

While the attractive videos help Holmes to achieve some rapid storytelling, the decision to put McGuire in a white suit only makes the character of Brian more clownesque than sinister. The constant use of slot machine and video-game imagery, the discovery of Gary in a cardboard delivery box and clumsy attempts at soliciting (ouch) audience participation — most grossly, the overtly ironic selling of badges and premium seats — is just too didactic for my taste. On the other hand, this show will totally delight anyone who wants a great big stonking fun evening, full of glitz and laughs. But if you, like the play’s characters, are looking for something more, some emotional connection, I fear you might be disappointed.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk