Bedroom Farce, Duke of York’s Theatre

Wednesday 31st March 2010

Alan Ayckbourn is a phenomenon. He’s popular theatre’s secret weapon, and is so often performed around Britain that, in some years, more people have seen his plays than those of William Shakespeare. The chronicler of suburban middle-class woes, he is currently enjoying a bit of a late-life revival as several of his works are being restaged in London, and beyond. Bedroom Farce, originally produced in 1976, is currently nicely tucked into a large West End theatre — but is it any good?

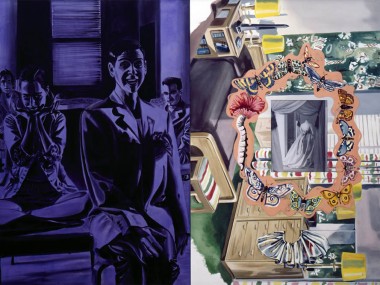

As ever, the set up is both clever and theatrical. In three different bedrooms, designed by Simon Higlett, four couples confront their relationships during one very long night. The three bedrooms belong to an old couple, a newly smitten couple and a couple who have been together a bit too long. Their names are Ernest and Delia, Malcolm and Kate, and Nick and Jan. Linking these six people is the couple from hell: Trevor and Susannah. Ernest and Delia are Trevor’s parents, Jan is a former girlfriend of his, and Malcolm and Kate are their friends.

As portraits of British marriage in the 1970s, the conventional wisdom is that these four examples are predictably grim. After all, Ernest and Delia prefer to tuck into pilchards on toast rather than have sex; Malcolm is apt to prefer DIY to sex; and Jan is so wickedly scornful of her husband that she snogs Trevor at a party. But, in Ayckbournworld, balance is all: despite this evidence of mutual loathing, these three couples are reasonably well adjusted — we laugh at them partly in self-recognition.

Trevor and Susannah are harder to take, but equally typical. These are two people who are always proclaiming their angst, and their problems, not just from the rooftops, but also in capital letters all over the sky. Selfishness rules. Most people have met a Trevor and a Susannah, and most will surely recognize the mixed reactions that the other three pairs have to them. Once again, we laugh at the awfulness while well aware that we are not all that different. Are we?

The middle-classes, Ayckbourn seems to be implying, are living in these emotional and sexual tangles because it is quintessentially British to prefer pilchards on toast to sex, and embarrassed evasions to talking openly about real feelings. In this, he has a point. And he also understands that the mission of populist theatre is that it should disturb slightly, but not really antagonize — and this is a good example of that genre.

But what about its quality? With the three bedrooms visible at all times on the stage, allowing the audience to compare the ghastly wallpaper and suburban decorations, Ayckbourn has to do a fair deal of shoehorning to make the characters arrive and depart — and this device does creak at times. More damagingly, all of his people seem to talk in the same plain language — his energies are thrown into the plotting so the characters are thin, and their language fundamentally uninteresting.

It’s playwriting alright, but it’s old writing. There’s no sense of risk in the creation of this onstage world, which is as familiar as an old slipper, and about as exciting. But it is, at the same time, undeniably funny. Like a good television sitcom, the exchanges are brisk and bright, and the darkness of this view of relationships hangs like a rather distant cloud over the horizon. You never really feel that anything is actually at stake.

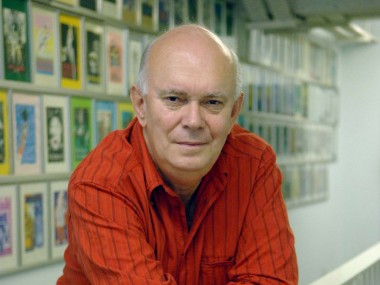

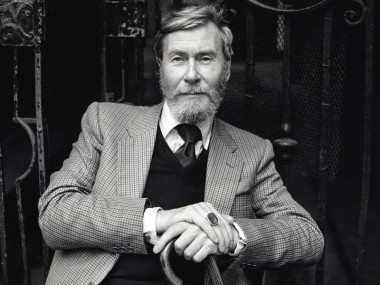

Veteran Peter Hall directs, and the best performances come from the actors playing the most extreme characters, namely Orlando Searle as Trevor and Rachel Pickup as Susannah. They are ably supported by Jenny Seagrove and David Horovitch as Delia and Ernest, Daniel Betts and Finty Williams as Malcolm and Kate, and Sara Crowe and Tony Gardner as Jan and Nick. Ayckbourn may be a phenomenon, but this evening in the theatre is as predictable as a night spent in front of the telly.

© Aleks Sierz