Sucker Punch, Royal Court

Monday 21st June 2010

Sport is central to black identity. But, oddly enough, there are few plays about the subject. This might be due to the limited imaginations of British playwrights, the difficulties of staging sporting events in theatres or the perception that sport is a different cultural sphere from theatre. Whatever the reason, here, finally, is a sizzling play about black men and boxing.

Roy Williams’s Sucker Punch presents a deft contrast between a good boy (Leon) and a bad boy (Troy), two young black men who grow up around an old boxing gym run by Charlie, a white trainer who is also a bit of a loser. His daughter, Becky, provides the love interest, although one of the points of the play is that women are marginalized in this male world. While Leon slowly becomes a successful boxer, Troy gets into trouble, thus creating a conflict which turns up issues of black pride and personal identity: you are what you do. At one point, Troy leaves to go to the USA. Meanwhile, Leon becomes a champ and is surprised to find out that his former mate has become an American boxing star. Inevitably, they must meet in the ring.

The questions that Williams raises are typically difficult: he always relishes the chance to say the unsayable about race politics, and this play is no exception. So is Leon a genuine sporting success or an Uncle Tom who sucks up to the whites? Is Troy a self-made man or just a money-making machine for his all-powerful manager? Has either, or both, betrayed their black heritage?

The acute contrast between strong American winners and weak British losers is further complicated by the attitudes of Leon and Troy to Charlie, who is a father figure to both. Leon’s real father is a no-hoper, a man constantly borrowing money for drink from his son. Yet even he is allowed his moments of true insight. Likewise, Becky is perceptive in her appraisal of the two sportsmen. The sexual politics of the play inevitably result in a female casualty, but this theme is secondary to the main thrust, which is an illuminating study of ambition, motivation and the will to succeed.

How does the colour of your skin help fuel the passion and commitment that success in sport demands? Williams gives several answers in a play that is short, but full of complexity. Played out against a social canvas that offers a sketch of the race politics of the 1980s, the story of Leon and Troy yields a forceful account how British black identity has evolved during an era of police harassment and urban riots. With the character of the white boxer, Tommy, Williams makes the racist ideas of the past vividly alive. But the play is also about much more: it’s about loyalty and male friendship.

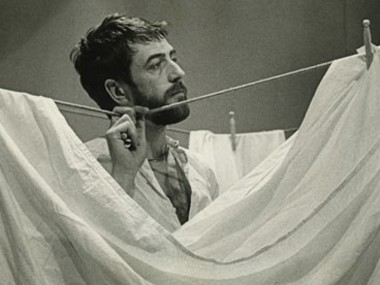

Staging boxing matches might be a problem so Williams sidesteps the issue by conjuring up these events through the verbal poetry of Leon, who talks us through most of the matches on designer Miriam Buether’s set, which sees this venue remodeled into a sports club, dominated by a central boxing ring. In Sacha Wares’s exciting production which, with help from choreographer Leon Baugh and boxing trainer Errol Christie, features some thrilling music and sound effects, only the climactic fight is an actual boxing match, and even this is stylized and symbolic. A uniformly strong cast — led by Daniel Kaluuya and Anthony Welsh as Leon and Troy, with Nigel Lindsay as Charlie — make this a punchy (sorry) account of both sport and the making of black identity in today’s Britain.

© Aleks Sierz