Pygmalion, Garrick Theatre

Friday 27th May 2011

Is the Pygmalion myth inherently sexist? In Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Pyg was a Cypriot sculptor who carved a beautiful figure of a woman out of ivory and then fell in love with it. Of course, she was perfection incarnated and when he kissed the statue, Venus turned it into a live woman. No need for any mail brides in Ancient Rome. But isn’t there something that sticks in your craw in this picture of the creative male and passive female? And can a starry production soften this irritation?

Certainly, George Bernard Shaw’s 1916 play, Pygmalion, has enough pompous masculinity in it to turn the strongest stomach. The tale is that of the upper-class Henry Higgins, a phonetics professor, his colleague Colonel Pickering, and their bet over whether they can transform the much younger Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney Covent Garden flower girl, into a lady within six months.

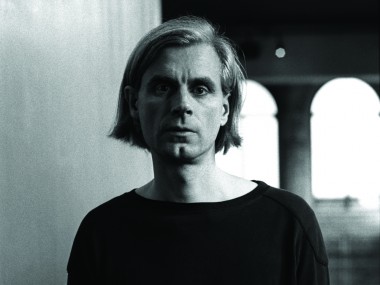

At first, the situation favours the snobby Higgins and allows him plenty of opportunities to belittle Eliza, with lashings of sarcasm and oodles of condescension. It’s not a pretty sight, and a bearded Rupert Everett in the staring role gives an acidic quality to every line. But, however watchable, this actor fails to convey the character’s fun-loving side.

Then, in the fine final scene, Eliza — having triumphantly become transformed — manages to turn the tables on him, asserting both her freedom and her individuality. In Strictly EastEnder Kara Tointon’s attractive and occasionally radiant performance she comes across as a woman who has found herself — despite rather than because of the manipulations of the older men around her.

Yet what is also clear in this thrillingly complex final scene is Shaw’s deep emotional ambivalence about his characters. You can really feel him struggling to reconcile his identification with the man (after all, like Higgins, Shaw is responsible for creating characters) and his awareness of the needs of the woman. At the same time, Shaw is also attempting to imagine and articulate a different idea of friendship between an older man and a younger woman. You could even say that this is the emotional core and intellectual nub of the play, and one which gives that final scene its compelling power.

There are also some other delights in this show, chief of which is the character of Mr Doolittle, Eliza’s father. A self-confessed member of the undeserving poor, this symbol of middle-class fears is a richly comic character whose every utterance is a joy. Although Shaw is turning a widespread fear of the underclass into a humorous turn, Doolittle gets some great lines, neatly rendered by Michael Feast.

Likewise, in this version, Eliza is given some lines which suggest that working-class people are somehow more authentic than the artificial upper-middle-classes, that they know more about life. Could this be one of the origins of the myth of working-class authenticity, which was later explored by 1950s playwrights such as Arnold Wesker? Designer-director Philip Prowse’s production is design-heavy, with a campy mix of glowing lights and soft pinks, plus some elegant furnishings. Operatic music blares from the stage. But most of the acting, in a cast which also boasts Diana Rigg as Higgins’s mother, is traditional and unexciting. If you are not already sound asleep by then, the last scene is the best. But before that, there’s a lot of sexist rubbish to be endured.

© Aleks Sierz