About Making Noise Quietly

Tuesday 1st May 2012

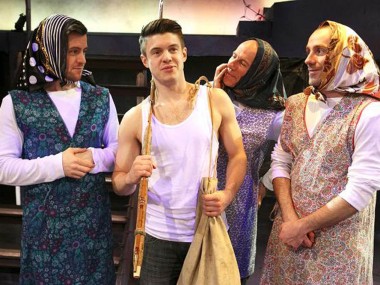

British theatre culture is blessed with an abundance of playwrights. It is the writer’s unique, singular and individual vision that is served by directors, actors and designers. But that does not mean that all playwrights are treated equally. Some languish quietly in obscurity, while others bask in the warming glare of fashion. A good example of the former is Robert Holman, who has been writing since the 1970s but whose work is relatively unknown, mainly because he has a much milder sensibility than that of the louder and brasher brat pack playwrights often favoured in our culture. His Making Noise Quietly, first staged in 1986 and which I saw a week ago at the Donmar Warehouse, is a neat trilogy of short pieces about the effects of war on ordinary people. In the first playlet, Being Friends, there is a chance encounter, which takes place in Kent in 1944, between a conscientious objector and a gay artist. The second, Lost, concerns a naval officer who visits the mother of another naval officer and discovers that no one has told her that her son has been killed in the Falklands war. The third, and by far most profound, piece is called Making Noise Quietly. In it, a British squaddie traveling in the Black Forest in 1986, with his eight-year-old stepson, comes across a local woman who turns out to be a concentration camp survivor. As the squaddie tries to face up to the terrible effects of war on his temper, and on his ability to communicate with his stepson, the old Jewish woman gives them both a simple lesson in humanity. As directed by Peter Gill, this is a beautifully delicate evening, with humane performances from the whole cast. Matthew Tennyson is the campy artist and Jordan Dawes the conscientious objector in Being Friends, while Susan Brown is excellent as the mother in Lost. Best of all, Ben Batt is the soldier and Sara Kestelman the woman in the wonderful final piece. Although none of these short plays tell us anything we didn’t know about the psychological destructiveness of war, and the ability of people to behave in an inhuman way, they amply demonstrate these ideas in a convincing and concrete manner. In the first and the final pieces Holman also offers glimmers of hope that people can change and that pain can be healed.

© Aleks Sierz