New Nigerians, Arcola Theatre

Monday 3rd September 2018

With Prime Minister Theresa May visiting Nigeria last week, trying to stump up some post-Brexit trade deals in Africa as well as taking the opportunity of teaching the world to dance, it is a fitting moment to watch Oladipo Agboluaje’s New Nigerians, which was first staged at this Off-West End venue in February 2017, and now returns — and I’m happy to say that it’s as fresh as ever. A vigorously written, warmly performed and lively satire about Nigerian politics, it opens with a radical politician, Greatness Ogholi, practising a conference speech to the newly formed People’s Revolutionary Party in which he announces his candidature for the presidency in the upcoming general election and outlines his vision for his nation and its people.

And what a vision it is: his theme is revolutionary change. To save Nigeria from rampant corruption and endemic economic crisis, he vows to take on the existing political establishment, whose main parties are parodies of their Western models, neoliberal in policy and servile to the global corporations which exploit the country’s resources. Instead of their strategy to divide and rule the nation by emphasizing its fractures, by region, by religion, by tribe and by class, he proposes a united front against poverty and in favour of local self-determination. It’s a socialist programme for a turbo-charged capitalist age. Breaking down the fourth wall, Greatness asks the audience to chant his slogan “One Nigeria, one family”, and solicits our feedback: we should watch him carefully to see if he compromises his integrity. Somehow we are sure that he will.

Problems soon arrive in the shape of Chinasa Obi, Greatness’s running mate, and a woman who hasn’t quite managed to kick the habit of smoking weed on all occasions. But as well as being comically addled, she also brings a cold dose of reality. Party recruitment is not going well: people are not signing up to Greatness’s vision. In one region, the People’s Revolutionary Party is nicknamed The Clueless Party. But, argues Agboluaje, unpopularity has never stopped a populist, and Greatness is extremely ambitious: he meets Danladi Musa, a businessman and rival who once even threatened his life, and tries to thrash out a deal to get his backing. But the inevitable compromises provoke audience murmurings.

Greatness also has a meeting, in a swanky hotel restaurant, with another man of the people, Comrade Edobar, a trade union boss. But, once again, compromise is the name of the game (more audience murmurs). Edobar is not an idealistic leader of labour, but a practical man who calls off strikes when he thinks things are going badly, and prefers to reach backroom deals rather than win through direct action. And as he’s aged so his principles have weakened. The two men also have some baggage: Edobar knew Greatness’s father, who has recently died and whose body still awaits burial. In this powerful metaphor of a dead father who remains unburied, Agboluaje articulates the personal costs of Greatness’s radical ambitions.

This theme is underlined when Greatness meets Grace, his wife from whom he is separated, to discuss the schooling of their daughter. Once again, his personal life is on hold: instead of being a real family man, he is shown as an egoist who neglects his private life while mouthing slogans about making Nigeria into one big family. Pure hypocrisy. Grace, who is a high-flying executive and a Christian, also provides a cool contrast to the heady politics of revolutionary slogans. She is well-adjusted and practical while Chinasa is stoned and febrile, the latter more an impediment than a helpmeet. Gradually, amid the lashings of humour and audience participation (be ready to clap), we realize that Greatness has little chance of living up to his name.

As a satire on Nigeria’s current ruling class, which prefers to travel abroad to London to get treatment even for comparatively minor ailments — such as an ear infection — than to trust a Lagos state hospital, Agboluaje’s play hits its targets fairly and squarely. Amid the humour, which is full of local references that only those familiar with Nigeria can instantly understand, some more general points are being made. When Greatness buckles under the reality of having to make political deals, one thinks of those Jeremy Corbyn supporters who will have to reconcile political idealism with practical politics, or stay — like Greatness — out in the cold. As usual, the charge of hypocrisy is always lurking in the wings.

An even deeper idea is being aired amid the chuckles: in the second decade of the new millennium, is the concept of revolutionary change inherently risable? Although populist movements are making waves all over the world, from Trump in the United States to European right-wing parties, none of them seems intent on either social justice or economic development. Profit is more important than civic ethics, blaming the weakest members of society seems to get more votes than standing up for them. In this context, the vision of a People’s Revolutionary Party seems nostalgic at best, and cruelly ridiculous at worst. Although, like Corbyn’s Labour, it might work as a protest movement, it hasn’t a hope of governing. And without being in power, what change can it achieve? This might be the bitter sting in Agboluaje’s comedy capers.

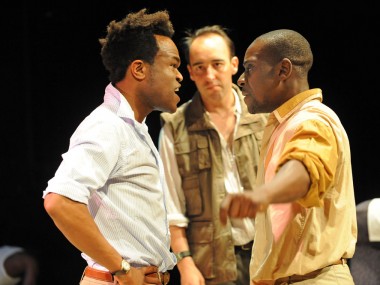

Rosamunde Hutt’s energetic production, on Jemima Robinson’s bright if rudimentary set, features an impassioned performance by Patrice Naiambana, who is both charming in his direct address to the audience and full of pent-up feeling as Greatness. Although he is a figure of fun, you can’t help but empathize with him. He is well matched by Tunde Euba, who doubles as Danladi and Edobar, and Marcy Dolapo Oni, who is very amusing as both the stoned Chinasa and the rather serious-minded Grace, as well as doing a nice turn as a waitress. The clowning is great fun, and this is the first show in which I ended up with cast member in my lap! While a play can never really change politics for the better, Agboluaje’s New Nigerians does give us the chance to laugh at corrupt politicians and to enjoy seeing our own human frailties being so joyfully satirized.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times