Dealing with Clair, Orange Tree Theatre

Tuesday 30th October 2018

On the morning when this stylish revival of Martin Crimp’s 1988 play opens, I wake up to the news that the police are following up a new lead in the Suzy Lamplugh case. She was a 25-year-old estate agent who disappeared on 28 July 1986, and was officially declared dead in 1994: she went missing after leaving the office to show a house to a mysterious client, Mr Kipper. Although Crimp did not base his play, which is mainly about the greed of people in the house-buying boom of the late 1980s, on this cold case, it does hover at the edge of the play, emitting a disturbing vibration. Oddly enough, the Lamplughs were a family that lived locally to this venue, which is not only reviving the play, but was also responsible for its original staging.

Dealing with Clair is set in the pleasant middle-class home of Mike and Liz, a young couple who have one baby daughter and a live-in nanny, the Italian Anna. As they decide to sell their house, they find themselves dealing with Clair, a young estate agent, who has a pragmatic view about gazumping and doesn’t object when they reject an initial good offer by an out-of-town couple in favour of a new cash buyer, James. Although James claims to be rich and to have a wife and family, it slowly becomes evident that he is not all that he seems. In fact, there is something distinctly creepy about his attitude to Clair in a story which is both about selfishness and irresponsibility in the housing market, and about male attitudes to women.

It begins as a satirical portrait of Mike and Liz’s comfortable and contented lifestyle. Whenever their baby cries, they call for Anna to look after her. And, like lots of middle-class folk, they want to behave ethically, but, gradually, they allow their avarice to get the better of their more moral instincts until a disturbing picture of a kind of “greed is good” capitalist society pervades the whole play, in which every character is pretty unattractive. Most disquieting is the latent violence that simmers close to the surface whenever the men speak. At more than one point, a man calls a woman a “girl”, and then apologies for belittling her, itself a form of mansplaining. And, even in the apology there’s a sense of menace. Occasionally there’s a verbal detonation: at one point Liz suggests that the drunken Mike wants “to rape Clair”.

For this revival, Crimp has slightly rewritten the text, adding a mobile phone here or raising a house price there, but much of it retains the original’s freshness and attack. Dialogues are rapid, angular and jagged, with repeated words emphasizing Mike and Liz’s feeble morals and James’s eccentric if chilly charm. Rarely has the word “turmeric” had such a ambiguous force. In his mouth, it does. The couple’s desire to behave “honourably” in the sale of their property is in stark contrast to the way they treat Anna, who is confined to a tiny windowless room in a house that has three other bedrooms. And James’s curiosity and perceptiveness, and his understanding of Clair’s essential loneliness and unhappiness, suggest a psychopathic personality, an invader of this suburban normality.

In a story about normal, if slightly sad, people, James stands out because of his intensity and his gift with words. He is unusual. Whenever he speaks, he seems ready to enthrall, to persuade and to seduce. It’s fine to listen to him, but keep your distance. Both magnetic and macabre, you instinctively recoil from his mannered charm, and instantly fear for the safety of anyone who gets too close to him. Although he has greater understanding that the rest of play’s characters, you also feel that he will not put this to good use. For a show that opens on the eve of Halloween, James is the night’s dark creature.

With its talk of solitude and the inscrutability of other people, there is an existential edge to the story, while Clair’s own tiny rail-side flat eerily prefigures the storyline of Paula Hawkins’s 2015 novel, The Girl on the Train, with its suggestive mix of excessive drinking, unhealthy curiosity and intrusive voyeurism. Likewise, here there is a constant edge of unease, as tongues loosened by drink bicker and snarl, and the dialogues are not only carefully articulate but also cruelly, if often subtly, savage. Sexual desire and a sinister will to dominate snake in and out of the story, unsettling our better natures even when the exchanges provoke a chilly laugh. This really is a masterpiece of contemporary new writing.

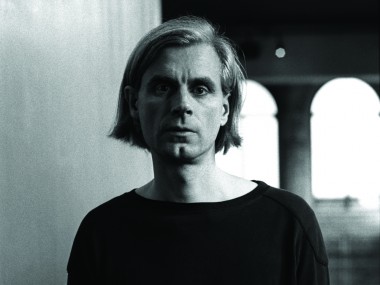

First seen 30 years ago, at the same venue which staged all of Crimp’s early plays, this revival is excellently directed with energy and imagination by Richard Twyman, artistic director of English Touring Theatre, the show’s co-producers. Designer Fly Davis’s set is a gauze-sided box, which puts all the characters into something like a fishbowl, where we can spy on their absurd posturings. Michael Gould is fascinating as James, exuding intensity and danger, as he encourages Lizzy Watts’s restrained Clair to abandon her self-control, while Tom Mothersdale is brilliant as Mike, a man well able to conceal his nastiness under a smile. Hara Yannas and Roseanna Frascona are both completely convincing as Liz and Anna. In the current housing crisis, and in the context of #MeToo, this is a play that is not only relevant, but also powerfully affecting.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times