Cougar, Orange Tree Theatre

Tuesday 5th February 2019

Okay, let’s start with a definition: “Cougar: an older woman who actively seeks the casual, often sexual, companionship of younger men, by implication a female ‘sexual predator’” (derogatory slang, Wiktionary). Although this label is unflattering (the unspoken assumption being: how dare older women have designs on younger men?), Rose Lewenstein inverts some of these preconceptions in her short and slender new play, which has been staged by this venue in a co-production with English Touring Theatre. But although it’s main theme is the relationship between an older woman and a younger man, the playwright also creates a chaotic background to the story in which the world is pictured as a threatening place, with the twin monsters of global warming and consumer capitalism licking their lips as humanity hurtles towards an apocalyptic end.

The love story shows the relationship between Leila, a high-powered environmental consultant who travels around the world persuading corporations to adopt more sustainable policies, and John, a Liverpudlian who does bar work. She is in her mid-40s; he in his mid-20s. She enjoys a hugely successful career; he is at a loose end. They meet at the end of one drunken evening, some climate change event, when John intervenes during a row between Leila and a senior male colleague. After a few more drinks, he ends up in her hotel room, and the play — whose dazzlingly form is some 80 rapid scenes spread over a mere 75 minutes — takes place in a succession of hotel rooms, which all look the same, but are located all over the globe.

This is because Leila and John have made an arrangement. As she jet-sets around the world, from one conference to another, giving keynote speeches, he tags along, sharing her room, sharing her bed. She pays for everything; he does nothing. She won’t tell him about her home life; she doesn’t ask about his background, or his family. When they return from each trip they go their separate ways. It’s a deal: she buys his company and his body. A situation which neatly inverts the old idea of the powerful male who has a kept woman, and shows that inequalities of power are just as miserable when the strongest partner is female. But there is something appealingly refreshing in seeing the role reversal, the tables turned.

If this relationship was simply presented in a linear way it would soon get tedious. Leila’s job involves giving more or less the same speech at more or less the same conferences in different world cities, from the States to Russia, from South Africa to Brazil and India, and a dozen European locations. At first blown away by the exciting richness of this lifestyle, John soon finds that time hangs heavy on the hands of a toy boy. He resolves to learn a foreign language; or maybe take photographs of the exotic locations he finds himself in. Anything, really, to pass the hours. But the unequal commitment of these rather fragile personalities soon puts a strain on their relationship. After all, falling in love was definitely not part of the deal.

To her credit, Lewenstein makes this situation more interesting by the way she structures the play, which takes the idea of fragmentation to the extreme. Some of the scenes are barely a minute long, they jump around in time, and the rapid shifts in locations (while the hotels rooms stay the same) have a cumulatively dizzying effect. The episodic nature of the events suggest half-remembered memories, tiresome repetition and even emotional fracture. As the planet heats up, and the relationship between Leila and John comes under strain, the story gains a strange intensity, a kind of descent into the underworld. Added to the obvious political contradiction between saving the planet and clocking up thousands of air miles, the imagery of play, from the rapacity of the cougar to a climactic vision of a carnivorous world in which we cannibalise each other, comes vividly to life.

It’s a picture of super-exploitation in which the rich literally end up by feeding off the poor, while the world descends into a jungle of chaos. Although Leila represents female power — the seducer, the buyer of clothes and the earner of a massive salary — its final effect is no different from male power. Different corporate suit; same misery. And although she tells John that she has sex with other people, this predatory behaviour changes little in the sex war. By the end of the play the overwhelming emotion is that of disgust. Disgust with money; disgust with the world. Time to smash up the hotel room. While a trashed room evokes memories of Sarah Kane’s Blasted and Polly Stenham’s Hotel, and the set up recalls that of Last Tango in Paris, the strongest theatre influences are surely Caryl Churchill, whose radical experiments in form are clearly an inspiration, and Martin Crimp, who specializes in creating scenarios which put couples under pressure. Coincidentally, the power play shown here has affinities with Crimp’s latest, When We have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other.

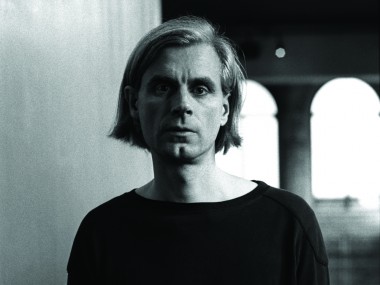

Chelsea Walker’s sharp and hectic production gives the story a real zing, and Rosanna Vize’s set, with its bed and glass panels suggests the anonymity of five-star accommodation everywhere. Part of the excitement of the play is that of watching an extramarital affair; another part is feeling that the world is burning up in front of you. Both actors are excellent: Charlotte Randle exudes a cool authority whose privileges are sexual as well as financial, but she also suggests an emotional blankness which mirrors the blankness of her globe-trotting world. Mike Noble, at first awkward and easily impressed by luxury, gradually becomes more angry, more frustrated and more desperate. With such good work, this sketchy two-hander becomes suggestive enough to book a long stay in your mind.

© Aleks Sierz