The Normal Heart, National Theatre

Friday 1st October 2021

Hypocrisy. Is this the right word? I don’t mean the play, but the audience. Of course, in the middle of the current COVID 19 crisis, there’s bound to be a certain amount of discomfort when watching Larry Kramer’s 1985 modern activist classic about the AIDS epidemic, since both cost many thousands of lives, but it feels really odd to me to be in the middle of a National Theatre audience where only half are wearing their masks. So while everyone cheers this story about how selfishness has to be challenged in order to preserve public health, only half are acting unselfishly to keep us all safe. In this case, hypocrisy seems a rather mild word.

This is a shame, because feelings like this are a distraction from the show, which fully retains its campaigning power and finds a new resonance in today’s Britain. Set in 1980s New York, The Normal Heart (whose title refers to a line from WH Auden’s “September 1, 1939”) is an autobiographical play about how a group of gay activists challenged the city authorities, the central government and the medical profession with their desperate pleas about taking the AIDS epidemic seriously. The central protagonist, modeled on Kramer himself, is Ned Weeks (Ben Daniels), whose anger at how the mainstream media ignores the disease motivates him to start an activist organisation to spread the word and save lives.

Spanning the time between July 1981 and May 1984, Kramer’s play dramatises Weeks’s fight, which soon exposes tensions within the gay community. Weeks, a Jewish writer, has a “big mouth” and favours using shock tactics, such as personal attacks, to carry his message home, while others, such as their organisation’s president Bruce Niles or fellow activists Tommy and Mickey, prefer a less confrontational and more ameliorative approach. Added to this Kramer beautifully outlines Weeks’s private life: his love affair with New York Times writer Felix Turner and his psychologically tangled relationship with his brother Ben, a successful lawyer more interested in building a million-dollar house than in telling truth to power.

Kramer is careful to evoke the deep homophobia of the early 1980s, a time when coming out could result in your being sacked from your job in a corporate bank or the health department. So while Weeks’s verbal assaults on compromise and timidity are written with passionate intensity, Kramer acknowledges that others within the gay community also have a point. In fact, while Weeks fails to persuade New York’s mayor to take action, the others belatedly succeed. Nevertheless, the story is told from Kramer’s point of view and its main thrust is that of committed militant drama. Some of the best scenes are his interviews with Dr Emma Brookner, a clinician who clearly outlines one of the central issues of this issue-based play: personal responsibility.

Brookner’s argument is the unwelcome truth that the only way to combat this new disease is to stop having sex. Before the creation of anti-viral treatments, and the widespread practice of safe sex, the gay community was certainly vulnerable to infection in bathhouses and other palaces of pleasure. But, of course, for a community that had endured centuries of prejudice, the joy of sexual liberation was a central core of self-identity. So Brookner and Weeks’s message does not go down well — indeed, they are accused of scare-mongering and of pushing gays back into the closet. Yet the need to question notions of individual freedom in a public health crisis, to balance personal pleasure against the public good, has never been more relevant. Isn’t this why I feel that people who don’t wear masks in public are so selfish?

Although Kramer’s militant drama is light on subjectivity, and his writing style is impersonal, with a preference for debate over imaginative metaphor, there is a clarity and pace in this story, with its good guys, bad guys and in-between guys, that lifts the play above the usual run of docu-dramas. Like Russell T Davies’s Channel Four series It’s a Sin, the stories of disease and death, with mothers reunited with sons on their deathbeds, have an undiminished power and potency. These moments bring back the full horror of those terrible times. And some lines — such as “We are living a war while they are living in peace time” — perfectly illustrate the indifference of the mainstream world to the gay community, and remind us that this disease still has the ability to return and ravage lives.

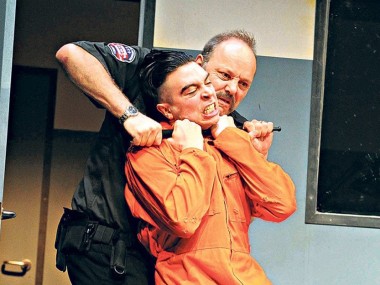

Dominic Cooke’s in-the-round production, on Vicki Mortimer’s grey utility set, begins with the lighting of a commemorative flame, and a snatch of disco-queen Donna Summer’s inspiring “I Feel Love”. By sharp contrast, we are immediately plunged into Brookner’s waiting room and Cooke guides us through the story, stressing the humorous put-downs as well as exploring the deep emotions of the main characters. Daniels is triumphant as Weeks, giving full rein to sadness as well as anger, and he has a real rapport with Dino Fetscher’s excellent Felix. Liz Carr is passionately intelligent as Brookner, while Danny Lee Wynter and Luke Norris are perfect as the “Southern bitch” Tommy and the ever-so-cool Niles. I also liked Robert Bowman as Ben, whose scenes with Daniels are emotionally complex. On the night I saw this show, after the applause, gay activist Peter Tatchell stood up in the stalls to remind us that Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives also tried to ignore AIDS and that they attempted to criminalise the gay community through the notorious Section 28 — he got a round of applause too. Yes, this is not just a play, it’s an event.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk