The Glow, Royal Court

Friday 28th January 2022

Bizarre. Breathtaking. Beautiful. I leave the Royal Court theatre with these Bs, as well as others such as bewitching and beguiling, buzzing in my mind. Alistair McDowall, whose previous leftfield plays include Pomona (2014) and X (2016), has created a mind-bending and time-hopping epic story which mixes Victorian gothic spiritualism with sci-fi wonderment, and is both dazzling in its imagination and dizzying in its theatricality. Without a doubt, this is the best piece of new writing on the London stage today.

It’s 1863. In the stygian gloom of a windowless asylum cell, a nameless young Woman is visited by Mrs Evelyn Lyall, a spiritualist who rescues abandoned souls not for philanthropic reasons, but in order to use them for her seances. To be vessels for the spirits of the dead to manifest themselves in true Victorian gothic style. As this 40-minute act unfolds, Mrs Lyall, unwillingly assisted by her son Mason, performs her spiritualist experiments on the person she has named Sadie. With surprising and brain-twisting results.

After the interval, it’s the year 1348. The same Woman is being taken by Haster, a hairy medieval knight, perhaps a kind of Fisher King, on an Arthurian quest, but things don’t go to plan. Then it’s World War Two. Now it’s 1993, and the Woman — who was named Brooke by Haster — finds sanctuary in the home of Ellen, a retired nurse. Then it’s 1979 and Brooke meets Evan, a young independent scholar who is obsessed with myth and folklore, especially the evidence for the existence of a symbolic female spirit, who glows and can be either witch or demon.

As the play time shifts from one historical era to another, and back again, with wild leaps into the lower paleolithic age, Roman times, 343AD, and timeless space, the Woman becomes a metaphor for loss and loneliness, a symbol of the spiritual homelessness and uprootedness of humanity, a mythical wanderer who can terrify or inspire. Her pain is humanity’s pain; her anguish our anguish; her love — humankind. By the end of the evening, as she gives voice to a poetic and apocalyptic vision of creation and destruction, the effect is strangely moving and the emotions are fully engaged.

The figure of the Woman alone, a female waiting for untold eternities is explained by McDowall in a spoof ‘Afterward’, written by an academic historian, which links the book that his Evan character is reading, The Woman in Time by Dorothy Waites, with both Arthurian legend and enthusiasts for the idea of witch cults in medieval Europe. Although both Waites and this academic are fictions created by McDowall, they are one key to his imagination. The play thrillingly brings together real-life Victorian sexual explorers such as Arthur Munby, spiritualists genuine and fake, and the ideas of American gothic writers such as HP Lovecraft and memories of the creature from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Maybe shades of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant. It’s rich in meaning and metaphor.

One image is that of the Woman cast deep into unlit dungeons, a prisoner in the profoundest solitude. This suggests our fear of abandonment, death and the void. It also acts as a powerful metaphor for the age-old suspicion of female power — what cannot be controlled must be cast into the dark. Other elemental imagery includes the water motif, both in the name Brooke and in the evocation of streams and lakes. And, of course, the Woman, like Jesus, is also a figure that carries the light of the world. The glow. Somewhere, deftly knitted into the language, are Tennyson’s Idylls of the King.

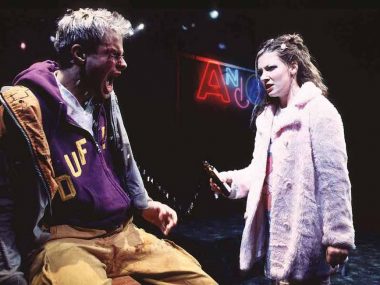

The Woman’s adventures across time are injected with enthralling life by Vicky Featherstone, in her exciting and wonderfully nimble production. A welcome challenge to the naturalism of most mainstream theatre, this extravaganza is gloriously theatrical, using haze, strobes, projections and sets that morph before our eyes. A cast of four — Fisayo Akinade, Rakie Ayola, Tadhg Murphy and Ria Zmitrowicz — play all the parts, with Zmitrowicz’s Woman both suffering painful horrors and being warmly humorous. Above all, she makes McDowall’s myth relatable. As Mrs Lyall, Ayola is strong and cruel, but as Ellen caring and compassionate, while Akinade’s resentful, angry Mason contrasts with his eccentric Evan. Murphy’s Haster is well rooted in feeling.

The acting is brilliantly supported by Merle Hensel’s versatile set, Tal Rosner’s video and Nick Powell’s sound. Some of the stage effects are amazing, others delightful. The wow-factor is high. For me at least. Not everyone will love this blend of myth, folklore and gothic fantasy, and there are occasional moments of awkwardness, but the final monologue conjures up a truly visionary picture of poor humanity lost in the wastes of space. The Glow certainly radiates an unforgettable feeling of spooky beauty, invoking a place where you can almost hear the hooves of the riders of the apocalypse. It’s haunting.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk