For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy, Royal Court

Wednesday 13th April 2022

What does it feel like to be British and black? Ryan Calais Cameron has recently emerged as the go-to guy for answers to this question. In February, the Soho theatre revived Queens of Sheba, his 2018 play, an adaptation of Jessica L Hagen’s debut about black women and misogynoir; now the Royal Court is staging For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy, which was first put on at the New Diorama Theatre last year. Cameron conceived the play in 2013 in response to the killing of Trayvon Martin, with the title echoing American playwright and poet Ntozake Shange’s seminal For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf of 1975. Like Shange’s play, Cameron’s is a choreopoem, a mixture of monologue, dialogue, dance moves and music.

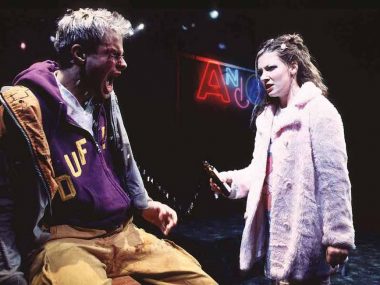

After a frankly rather portentous and pretentious opening, which features a slo-mo ballet and some awkward declaratory writing, the show settles down nicely. It starts with a couple of acutely sad stories about racist playground bullying, before talking about other shared experiences. Gradually, six characters emerge. All of them are symbolically named after aspects of blackness: the gemstone Jet, the mineral Onyx, volcanic Obsidian, the black-furred Sable, then Pitch and Midnight. They come from a variety of backgrounds and, as indicated by the line of plastic chairs arranged on stage, they are meeting in a therapy session (a framing device which is lightly suggested).

As they open up, various conflicts emerge. Sable is angry because he keeps getting stopped and harassed by the cops, but Pitch thinks that keeping street crime down is necessary. Onyx argues that black kids who go to university are “whitewashed” and become traitors to their heritage, while Obsidian counters that education is the only way out of poverty (he also hates the way black people use the N-word). Midnight thinks that learning about black history is disempowering because it reminds people of slavery, but Obsidian sings the praises of reading and finding out about the powerful African empires of the past. In one heartfelt exchange Jet and Onyx compare their experiences of fathers whose hardness, and refusal to appear weak, have devastating consequences. Cameron stages these conflicting ideas, but he is not arguing that they are directly responsible for the rise in suicide among young black men during the pandemic.

In the second half of the show, Cameron mixes comedy with self-analysis as Sable boasts of how his light skin colour enables him to seduce any woman he desires, but can never find love, while Obsidian proudly declares that his lover is not mixed race but a “beautiful black woman”. Pitch admits to being sexually inexperienced, while Jet, Onyx, and Midnight talk about their first sexual encounters. Midnight tells of his hurt when his babysitter seduced him when he was nine years old. Finally, Onyx expresses the pain of rejection and Jet talks about being black and gay. The cumulative effect of this is to show how self-doubt and self-hatred due to racism can affect a man’s whole life.

In the last part of the show, Obsidian tells a story about knife crime, while most of the others confess to feelings of depression and suicidal thoughts. The solution comes in the form of a joyous affirmation of the necessity of telling your own story, and acknowledging both strength and vulnerability. The main problem with this confessional and therapeutic format is that it suggests that all of these deep problems can be solved by simply voicing warmhearted feelings, when in reality depression takes months to work through. There is also something disturbing about the implication that being a black man means you need therapy. Many of the problems in the play stem as much from being a man as from skin colour.

Cameron’s play also seems to pull in opposite directions, offering a rather narrow range of experiences. He criticizes the monolithic single view of black maleness as unemotional and hard, and, at one and the same time, unconsciously perpetuates it. After the discussion about the whitewashing effects of education, the subject is dropped, and the range of characters remains limited to hipsters and young working-class men. Watching this show you would never know that black men are also teachers, doctors, engineers, social workers — in other words, middle class. Are they not as black as the streetsmart characters featured on stage? Don’t they have the same male problems?

Cameron writes in a mixture of poetic brightness and brute vernacular, and his tales of racial antagonism, police brutality and gang culture, as well as unrequited love and sexual anxiety, are articulated with a noisy energetic banter, whose outward joshing conceals the empathy of self-recognition. There’s a real zing on stage. Directed by Cameron and Tristan Fynn-Aiduenu (the show’s original director), and designed by Anna Reid, the event is joyfully entertaining in its choice of music, everything from the Mitchell Brothers to Sean Kingston, by way of Santana’s Spanish guitar and Snoop Dog’s “Beautiful”. Not to forget Aaliyah and Blackstreet. This play with songs and dance moves works hard and successfully to lift audience spirits by making trauma palatable as well as distressing. It’s fun as well as urgent.

Cameron’s cast are wonderful at giving their characters a sharp individuality that is instantly appealing. Mark Akintimehin’s Onyx exudes power as a threatening bad boy, and, like newcomer Kaine Lawrence’s Midnight, articulates the anger of young men who cannot bear injustice. By contrast, Nnabiko Ejimofor’s Jet and newcomer Darragh Hand’s Sable convey a sense of sweet pride as well as pain. Emmanuel Akwafo gives Pitch some brilliant comic timing as well as real depth, while Aruna Jalloh’s Obsidian is attractively smooth, but also agonized. But although For Black Boys… is strong on expressing the black British experience, its entertaining format does tend to defuse some of the potential explosiveness of its content. I just wish it was more dangerous.

© Aleks Sierz