How do musicals symbolize our national identity?

Tuesday 2nd July 2024

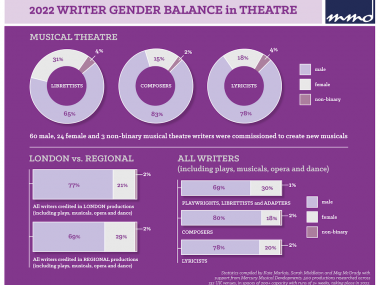

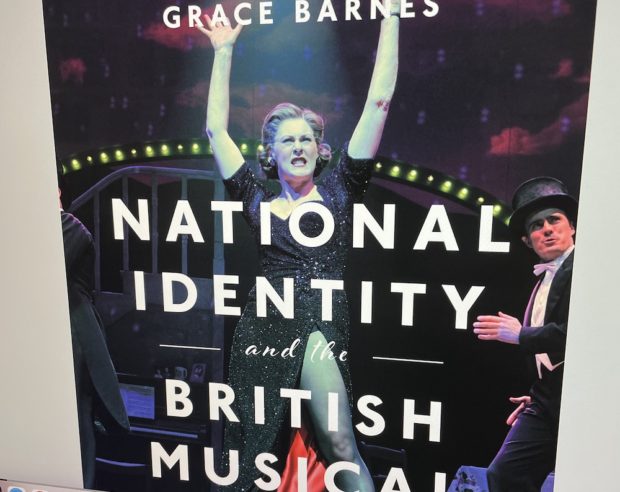

This clearly written and robustly argued new book, National Identity and the British Musical by Grace Barnes, provides an excellent overview of the relationship between musicals and our sense of ourselves as a country. Highly knowledgeable and thoroughly researched, it convincingly argues that “British musicals are frequently overlooked in national debates concerning culture and identity”. Unlike the USA where the musical has been central to ideas of popular culture and belonging, here the genre is often excluded due to “ingrained snobbery”, seen as mere “entertainment”, partly perhaps because of its working-class roots. This means overlooking the nation’s rich history of fun — such as music hall, panto, variety. end-of-the-pier shows, and working men’s clubs, much of which has fed into the musical over the decades. Barnes points out that while Geri Halliwell’s Union Jack micro dress is lauded as an inspiring fashion moment, the epitome of Cool Britannia and even Girl Power, the Phantom’s arguably even more globally famous mask icon is not. Over seven wide-ranging and tightly argued chapters, Barnes questions the whole concept of Britishness, looking at regional and national divisions in the UK, and emphasizing the absence of Black and Asian creatives in musicals, pointing out the lack of a UK equivalent of Lin-Manuel Miranda. She also advocates passionately in favour of The Big Life and Bend It Like Beckham as examples of work which feature narratives about immigrant communities. While showing how “British musicals, both historical and contemporary, are more likely to side-step any engagement with societal schisms”, there are also some acute critical passages about the English stereotypes of cheeky cockneys and sacrificial mothers. As well as race and class, sexism and the male gaze are analyzed in shows such as Made in Dagenham, which are characterized as having an inauthentic female voice because of the absence of female creatives in their production. An original criticism of SIX demonstrates how it equates sexual attractiveness and complicit objectification with female power. At the same time, Barnes stresses the utopianism of Billy Elliot the Musical and musical characters who defy macho roles, and sees Blood Brothers as one answer to the blockbusters of the 1980s, and an example of a political intervention. This superb analysis is followed by an equally interesting account of Howard Goodall’s less celebrated The Hired Man. The book has an impressive range of references, including Gracie Fields and Noel Gay as well as Andrew Lloyd Webber, and the Scottish socialist theatre of the 1960s and 1970s which often used songs and music. Other themes such as globalization and nostalgia are also explored. A lot of the controversies from past decades, when critics and commentators sneered at British musicals, are revisited, and her approach is a joy to read, being both balanced and convincing. The urgency of the question, “What kind of show do we want representing the nation in the future?”, is hard to deny, and the book ends by looking to the future with a call to transform the genre, imagining a Stormzy musical premiere at the National Theatre, and underlining the need for “honesty and a commitment to rethinking”. Time for the new decade’s London Road; high time to slough off our current British tendency to be “blinkered, exclusive and so mired in nostalgia as to be unable to move forward”. Time for change.

© Aleks Sierz

- Grace Barnes’s National Identity and the British Musical is published by Methuen Drama.