4000 Days, Park Theatre

Tuesday 19th January 2016

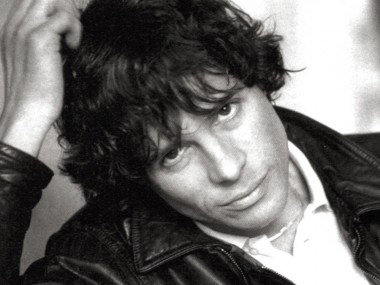

It’s a nightmare scenario — real horror show. You have an accident that leaves you comatose. You are out of action in hospital for three weeks and then, when you wake up, you gradually realise that you don’t remember anything of the past 10 years. Not three weeks, but 10 years! So what has happened to your life? This is the basic premise of Olivier- and Tony-award-nominee Peter Quilter’s new drama, 4000 Days, whose title aptly describes the gap in the experience of its protagonist, played by the ever-watchable Alistair McGowan.

Set entirely in a hospital room, this three-hander explores the situation of Michael (McGowan), who works for an insurance company, and ends up in A&E when he collapses due to a blood clot on the brain. Although the doctors are puzzled by his memory loss, which spans the previous decade of his life, the most traumatised person is Paul, Michael’s partner for most of that time. He discovers that Michael cannot remember a single thing about their relationship.

To up the stakes, Quilter adds Michael’s mother, the thrice-married and widowed Carol, to the emotional mix. She has never really liked Paul, and so she is glad that Michael doesn’t remember him. In fact, she reminds her son that he used to be a much more creative person before he met his lover, that he used to love painting. She thinks that Paul made Michael boring. At one point she turns on Paul and says: “You painted him beige.” She then tries to persuade her son to leave his partner and move in with her again.

The tug of love between Carol and Paul brings up a number of interesting issues, which include the notion of getting a second chance in life, the nature of memory, and the conflict between a mother and her son’s lover. Quilter shows how we actively create and recreate our memories, and argues that it is a mistake to give up our creative aspirations — even if they don’t pay the rent. The central point is that Michael stopped being an artist during his relationship with Paul, and now because of his amnesia can go back in time, starting off by painting a mural in his hospital room (how tolerant is our NHS). But although it is quite refreshing to see a gay relationship which is concerned more with love than sex, some of the writing here is bland and thin. But the performances are solid.

As played by the redoubtable Maggie Ollerenshaw, Carol is the spiteful mother-in-law from hell, a vicious monster who seizes the chance to cling to her son, emasculating him while at the same time proclaiming that “there is no greater love than a mother for her son”. The rather gentle and sensitive Paul has a real struggle to stand up to this maternal machine of total surveillance and control. And for most of the play he has little hope of success. Meanwhile, as Michael rediscovers his previous identity as an artist, he also begins to recover some fragments of memory. But, throughout the play, it’s the ideas rather than the characters that engage the interest, and much of the storytelling is pedestrian and lacking in dramatic power.

Matt Aston’s production is neatly designed by Rebecca Brower, but has some unimpressive video and wends its way leisurely through the rather banal twists of the plot while giving plenty of room for McGowan to express Michael’s pent-up frustration and sarcasm, while Ollerenshaw’s Carol has a similar amount of opportunity to pour bitter bile over her son’s relationship. By contrast, Daniel Weyman’s Paul is less demonstrative and more gentle, more feeling, more deep perhaps. If not enough is made of his creative side (being in marketing is surely not the most boring job in the world), it has to be said that the conflict between art and money deserves a deeper exploration than it gets in this rather underwritten and underwhelming play.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk