A Kind of People, Royal Court

Wednesday 11th December 2019

The trouble with prejudice is that you can’t control how other people see you. At the start of her career, playwright Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s work was set in her own Sikh community. But, like other playwrights from similar backgrounds, she has tended to be pigeonholed in the simplistic category of “Asian playwright”, and expected to write about clichéd subjects such as arranged marriage or religion. Now, however, she vigorously breaks free with this new play at the Royal Court, a story about life in contemporary Britain. This time she has expanded her cast of characters by creating a wonderfully multicultural community. But the worm in the bud remains racism.

A Kind of People begins as a warmhearted comedy. We are in the council flat of Gary and Nicky Sinclair, who have been a couple since their early teens. He’s black British; she’s a working-class white woman. He works an electrical engineer, she does shifts at a local pub, and tonight they are hosting a birthday party for his colleague Mark. Their Asian friends Mo and Anjum are also there, and so is Karen, Gary’s feisty sister. The children of both couples go to the same school and their parents are preparing them for the 11 plus. For the celebrations, Victoria — who is Gary’s manager at work and white — joins them and this could be awkward: Gary is going for a promotion, and she can’t hold her drink.

Amid the bright comedy of this opening, with its dance sequences, the play’s racial theme emerges when Victoria, in an excruciating sequence, is so drunk that she demands that Gary teach her how to twerk. He holds her off but, perhaps predictably, this has consequences when he is interviewed for the promotion. At the same time, tensions arise as Anjum tries to help Nicky to get tuition for her son Ronnie. While this help is appreciated, there’s a competitive aspect to this other couple which the playwright emphasises to good effect. Gradually, scene by sad scene, Gary and Nicky’s marriage comes under intolerable strain because of the pressures of work and their ambition that their children should have a better start in life. It all gets very depressing.

At its best, this is an empathetic study of the corrosive effects of racism: there’s an outstanding scene in which Gary, with a bit of help from his mate Mark, confronts a racist at work. He points out how when people look at him they only see a black man, not a human being. Or just another co-worker. The writing complicates this easy denunciation by allowing both men to lose their tempers and threaten the physically weaker racist. Further complications are also welcome: Karen doesn’t agree with her brother’s attack on the latent and persistent racism of British society, and there are tensions between black Britons of Caribbean heritage and Africans, and between black and Asian Britons. The sunny multicultural mix of the play’s start becomes increasingly turbulent. And this feels right.

Along with racism and sexism, another key consideration is class. Gary and Nicky are presented as aspirational working-class people, but by contrast the Asian couple — Mo and Anjum — have family support and connections that give them an economic advantage. There is class antagonism in their friendship because, when the chips are down, Mo and Anjum have more resources than the Sinclairs. They also have a religious network that can help them (she defends the wearing of the head scarf). By contrast, Victoria is in a position of power at work so her attitudes are inflected by the confidence that this economic position brings: she feels free to defend herself by using managerial language and is able to cloak her prejudices in evasive words. It’s a complex picture of a complex nation.

The main problem with this story is that, told at a brisk 95 minutes, there is not enough time to satisfyingly explore the relationship between Gary and Nicky, and most of the other characters are underwritten. Oddly enough, in a drama whose politics oppose stereotyping, most of the characters never develop beyond rather thin types. Sadly, there are also too many passages in which characters tell the audience what to think, instead of just showing us. So while there’s some powerfully provocative material — especially acute when Kaur Bhatti perceptively observes the stupidities of male behaviour (regardless of skin colour) — too much of writing feels like a first draft. At the end, it all feels rather incomplete.

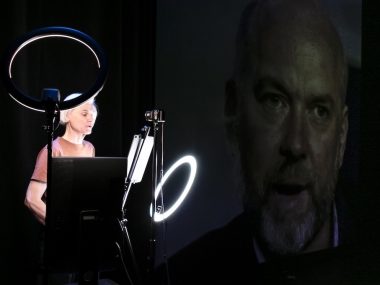

Michael Buffong’s production is unashamedly polemical, but is not helped by the fact that the Sinclairs’ ordinary council flat has incomprehensibly been designed by Anna Fleischle to resemble a city penthouse. As far as the acting is concerned, there are solid performances from Richie Campbell and especially Claire-Louise Cordwell as Gary and Nicky, with good support from Asif Khan and Manjinder Virk as Mo and Anjum. Thomas Coombes and Amy Morgan give Mark and Victoria some shades of complexity, while Petra Letang’s acid-tongued Karen is a real audience pleaser. (Her character deserves a play of her own.) But the trouble with this evening is that all this is not enough — you are left aching for more.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk