A Number, Young Vic

Tuesday 7th July 2015

The reason that Caryl Churchill is Britain’s best living playwright is that her work is endlessly enquiring and peerlessly intelligent. When she wrote this play about the subject of human cloning — which had its premiere at the Royal Court in 2002 with Michael Gambon and Daniel Craig as its cast — she avoided the obvious option of writing about how bad the idea of cloning is, and instead opted to explore its individual consequences. By doing so she came up with an unforgettable image of humanity in all its pain and anger.

The story is a family drama of a bizarre kind. Set in the near future, A Number explores the situation that develops after Salter, a father now in his sixties, meets three of his sons (two of them being clones of the first). But while it might even seem reasonable that a father would want to replicate a lost child, perhaps to make up for the deficiencies of his first attempt at parenting, the vision of the play opens out with the early revelation, suggested in the title, that a much larger number — about 20 — have been secretly and illegally cloned. Reasonableness turns into nightmare.

The 50-minute play is set in one location, Salter’s home, and follows his encounters with his two sons called Bernard, as the first one struggles with the fact that there is another, younger man, who is genetically identical to him, and the second one struggles with the fact that he is not the original he. The idea that there might be twins of ourselves living in society, people we could bump into, or spot in the distance, is disturbing to any idea of the unique individual. It also reminds us of cultural myths about doppelgängers, doubles whose appearance foreshadows death.

Churchill’s text is economic, but dizzying at the same time. If Salter is the father of some 20 men, are they all the same? They might look very similar, but what are they like as people? What would it be like to meet several grown-up versions of your own son? The emotional heartbeat of the play suggests ideas about having a second chance in life; and many of us might be tempted to have a second go at parenthood. Or, as kids, a second chance at playing the cards that nature has dealt to us. But the subtle subtext of the story implies that duplication can have unsettling effects on our subjectivity.

At the same time, Churchill’s dialogues are not only crisp and nimble, but have a metaphoric resonance which ripples out from the central human conflict between father and son. It’s as if she has created small strands of genetic material, each of which could be grown into a play of its own. There’s blueprint material here for a play about addiction (blame the genes, or not?), and another about failed marriage (blame the genes, or not?), and yet another about fatherly love (praise the genes, or not?). Yes, this is a rich text which is endlessly suggestive.

The gutsy centre of the play is all about murderous rage, fears of abandonment and the lust for love. The feelings are raw, fraying. At one point, the father is seen as a dark power; at another, the absence of the mother is hinted at. Childhood is a place of terrors; parenthood an experience of fear. And Churchill hints that the human capacity for evil is both casual, and not so casual. Thoughtless decisions have profound consequences. Happiness in life is, finally, a strange kind of gift.

Michael Longhurst’s powerful production is based on one good idea and one bad one. Like Mike Bartlett’s Game, the action takes place in designer Tom Scutt’s small box space with the audience peering in through wall-length windows. The good idea is the mirrors which enable the actors not only to appear as replicas of themselves, but also to react to their own images. The bad idea is that the glass of the windows distances the action, and muffles our empathy with the performers.

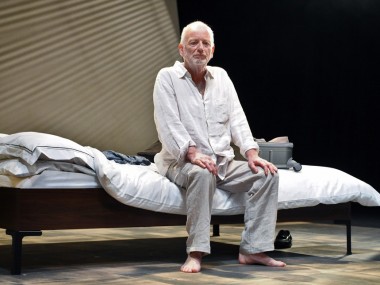

As is common practice with this play, a real-life father and son play Salter and the Bernards. John and Lex Shrapnel at first circle each other, prowling around the space like caged animals. The older man starts off pretty shifty, then becomes more and more desperate as he tries to confront the emotional and practical consequences of his own actions. The younger man plays three sons, each subtly different from the others. Looking at these two men you can’t help but experience the essence of the play: they are linked by their genes, but also highly individual. Each is much more than a number. Aren’t we all?

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk