A Very Very Very Dark Matter, Bridge Theatre

Tuesday 23rd October 2018

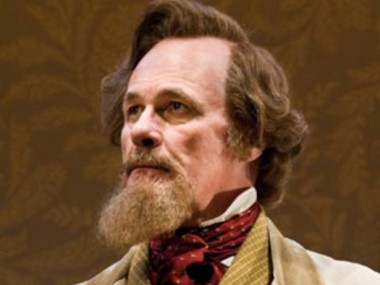

It’s all in the title, isn’t it? Martin McDonagh’s surreal new play comes with a warning that not only screams its intentions, but echoes them through repetition. Okay, okay, I get it. This is going to be a dark story, a very very very dark story. And, talking of repetition, the show’s cast is led by Jim Broadbent, who has form with this playwright. He was also in McDonagh’s masterpiece, The Pillowman, at the National Theatre in 2003 — and that was also a dark tale that was bleaker than bleak. Hot on the heels of the hilarious massacres of the recent revival of his The Lieutenant of Inishmore and the rather unfunny humour of his 2015 play Hangmen, what could this new one possibly have in store?

The play begins with a striking image. In a dismal Copenhagen attic, full of dusty broken toys, is a three-foot by three-foot mahogany box, which is occupied by Mbute Masakele, a Congolese pygmy woman who is the prisoner of none other than fantasy maestro Hans Christian Andersen (Broadbent). Not only does he hold her captive, but he has absurdly renamed her Marjory, then mutilated her leg, and now passes off her frantic writings as his own fairy tales. As the familiar gravelly voice of singer Tom Waits, pre-recorded, introduces us to this situation, which is set some time in the middle of the 19th century, Hans is portrayed as a silly fool, a sadistic clown who knows nothing about children and cares only for his own fame.

In the second part of this 90-minute show, the scene moves to London in 1857, where Hans visits Charles Dickens — whom he insists on calling Charles Darwin — and who it transpires also has what the publicity, perhaps unwisely, describes as “a dark secret”. The introduction of a Congolese pygmy into this comedy of literary manners, which is alarming similar to Sebastian Barry’s 2010 play, Andersen’s English (see what I mean about unoriginal?), is clearly a metaphor not only for artistic exploitation of other people’s experiences, but also for the European colonization of Africa. The image of the caged Marjory, packed like an exhibit at a fairground, is a cry against the monstrous crimes of Western imperialism, and specifically a denunciation of the genocide of African peoples in the Congo under the reign of Belgium’s King Leopold II.

Although historians might object that the Congolese atrocities — which cost the lives of some 10 million people — took place in the 1890s, long after the deaths of both Andersen and Dickens, McDonagh is clearly not interested in factual accuracy, but in black comedy and surreal imagery. And there’s plenty of that: at one point Marjory plays with a large spider puppet; at another, two blood-soaked Belgian colonialists arrive from the future, determined Terminator-like to eliminate Marjory from history. Elsewhere, McDonagh also draws literary parallels between Hans’s mutilations and sentimental images of Dickens’s characters such as Tiny Tim. And a “haunted” concertina and various guns also make this a ghostly Western, complete with shoot outs and profanities.

Despite the fact that the plotting is nonsensical, there are a couple of neat twists and, in a play in which the playwright freely and not very imaginatively plagiarizes himself (especially The Pillowman and The Lieutenant of Inishmore), the one genuinely inventive character is Marjory, the one-legged clenched fist of incarcerated determination who not only battles Belgians from the future, but also Danes from the present. But even she is a shadow of her more gloriously original cousins in The Pillowman, and in general there’s a discernible staleness about McDonagh’s vision here that is most evident in the fact that most of the jokes are simply not funny.

Okay, I get that the playwright is being deliberately provocative, and that he delights in being politically incorrect (pygmies?). But there’s a limit to how hilarious wanton acts of cruelty can be, and poking unimaginative fun at stereotypes of Belgians, Spaniards, Irish people and the disabled and mentally sick can soon become wearisome. Like Hangmen, this show is a compendium of sick humour and prejudice whose overt silliness becomes more and more tiring as the short evening wears on. It seems to me that as McDonagh has got older he’s lost both the imaginative freshness and energy of his early work, and that he lazily relies more and more on the same jokes, the same transgressions and the same shock tactics. And the same ideas about storytelling. Yes, we know that literary fantasy is born out of pain. How come? Because you’ve told us this before!

So this is a very very very feeble play which will appeal most to those desperate to see Broadbent on stage, although even they might be disappointed. His brash bonhomie as Hans is, to me at least, a case of one-note acting and a disappointing effort. Even worse, the underwritten parts of Charles and Catherine Dickens give Phil Daniels and Elizabeth Berrington little scope except for cheerfully hurling a few swear words around the place, which any other actor could do as well. Likewise, the rest of the huge cast do very little — with the singular exception of Johnetta Eula’Mae Ackles as Marjory, a character study that is not only powerfully convincing, but is also a really remarkable stage debut. She’s excellent. If she is undoubtedly the star of the show, its creepy atmosphere is down to director Matthew Dunster and designer Anna Fleischle, but in the end their creation is less twisted and funny than simply tiresome and tedious.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk