Antonioni Project, Barbican Theatre

Thursday 3rd February 2011

In this postmodern, digital age, the great masterpieces of modernism — whether in drama, in the novel or in film — seem like very distant shadows that beckon weakly to us from a very long way away. Ah yes, the old days, that time when people took art seriously, when what artists said actually mattered. You can still watch modernist director Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960s films and marvel at their existential spirit. But can this sense of meaningful adventure be translated onto the stage?

Antonioni Project by Amsterdam’s Toneelgroep attempts to squeeze three of the Italian master’s 1960s monochrone films — L’Avventura, La Notte and L’Eclisse — into a mere two hours and 20 minutes. So here again is a fragment of the tale of Anna from who in L’Avventura (1960) mysteriously disappears and whose lover, Sandro, pursues Claudia, her best friend; Lidia and Giovanni from La Notte (1961) each seem to suffer a midlife crisis; and in L’Eclisse (1962), an affair between a young, money-obsessed stockbroker Piero and Vittoria slowly moves into view. And the plot involves Vittoria’s mother, who also trades on the stock exchange, and Giovanni is finally drawn to Valentina, an industrialist’s daughter.

As you can see, this is a milieu of well-healed high achievers who can enjoy neither the riches they accumulate, nor the sexual relations that they drift into. As the programme note explains, these are couples for whom sex is easy, but emotional intimacy impossible. An air of exhaustion hangs over their dealings with one another. In the early 1960s, huge strides in economic growth were occurring in a society still dominated by old ideas and values. To break taboos, to transgress, was an adventure with no certain ending; too late for Victorian morality, too early for the feminist movement, the characters seem adrift, confused, vulnerable and — with only a couple of exceptions — unstable.

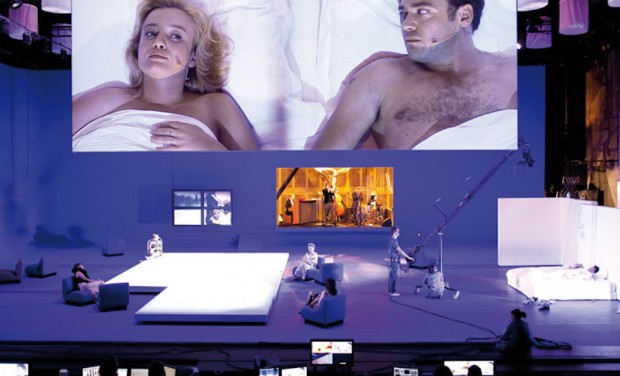

But the existential crises of the 1960s don’t survive completely unscathed in this contemporary staging. Toneelgroep’s production shows a film set on the stage level, with a huge screen above, on which the actors are projected, often with added backgrounds, with the result that we see every detail of their faces hugely amplified, as well incidentally as their mics. The screen images have not been aestheticised and come across as crude video pictures. So the magic of Antonioni’s films is lost in this transition, although the sense of emotional bafflement is well conveyed.

But there is no sense of ennui, or really of political radicalism. Instead, the staging is immensely well worked out and occasionally very clever. But, compared to similar experiments by Katie Mitchell at the National Theatre, it is a lot less aesthetically pleasing, and less well acted. Mitchell remains the master of this kind of work. Here, the video images of the sea are much more successful that the rather banal Götterdämmerung sequence in which operatic music from Richard Wagner’s Twilight of the Gods plays over scenes of ecological disaster.

Certainly, the show is also saying something about artists and creativity, but it is mainly mumbling, not articulating. Toneelgroep’s director Ivo van Hove, video techie Tal Yarden and designer Jan Versweyveld have created a watchable stage piece, but also one which rapidly becomes quite tedious. After the novelty of the split between the live acting and its projection as film wears off, you are left with little, but the usual questions about representation in art. What’s missing is the sense of Antonioni’s moral questing, political radicalism and aesthetic perfection. Although, come to think about it, maybe this crudity is itself indicative of where our culture is today.

© Aleks Sierz