Art, Old Vic

Wednesday 4th January 2017

Last year was the worst in living memory. At least, that’s what everyone I know is saying. Of course, my circle of friends is pretty limited — I don’t know any Brexiteers nor any Trump supporters. No, not one. But what if I did? How would I handle disagreements? So it struck me as particularly apt that the question of disputes among friends is at the heart of French playwright Yasmina Reza’s 1994 comedy, Art, which (typically) I am belatedly catching up on. So my first show of 2017 is a 2016 production.

Old Vic supremo Matthew Warchus is not only reviving this play, he’s also revisiting one of his major career triumphs. This twentieth anniversary revival of Reza’s global hit is a reminder that Warchus directed its London and New York premieres in Christopher Hampton’s sparky translation. His production, originally starring Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay and Ken Stott, ran — it says in the programme — for some eight years in the West End, and was kept going by being recast on a regular basis, with a rota of top-flight actors rubbing shoulders with stand-up comedians. And, indeed, it’s a gift for actors.

The evening begins as Serge (Rufus Sewell) shows off his purchase of a new painting to his best friend Marc (Paul Ritter). It’s a picture of white lines on a white background, and he’s paid 100,000 Euros for it. When Marc mocks his taste and his judgement, Serge is hurt and angered. Their mutual friend Ivan (Tim Key), a natural peace-maker, gets drawn into the conflict as he attempts to reconcile their differences. In a series of argumentative scenes, supplemented with direct address to the audience by all three, their 15-year friendship is put under strain.

All are middle-class professionals at different stages of marital life: Serge is a divorced dermatologist, Marc a married engineer and Ivan a bachelor who’s about to tie the knot. He’s also employed in the stationery business by his father-in-law. In Warchus’s production the trio arrive on stage in suits and ties, and gradually dress more casually as the 90-minute show speeds by. Reza skillfully sketches out their characters: Serge is the humanistic intellectual, cool, curious and cultured; Marc the strong authority figure, angry, critical, opinionated and philistine; Ivan the naive, jokey coward, always trying to smooth over conflict, but aware enough of his problems to be in therapy.

Reza’s writing brilliantly conveys the relationships of the three men. The vivid simplicity of the dialogues means that the central theme of masculinity in crisis, so typical of 1990s theatre, comes across loud and clear. Any audience can enjoy the perceptive, humorous and often absurd exchanges without strain. It’s all here: the tendency of mates to hero worship each other, to disparage the weak and inflate the strong, to attack each other’s women or to be jealous of each other’s accomplishments. There’s enough aggression, violence and betrayal on stage to satisfy the most jaded palette.

But if Reza’s view of maleness is laced with an amused archness, the politics of her play are pretty populistic. (That means reactionary!) All of the good jokes are at the expense of contemporary art (it’s a con), contemporary literary theory (deconstruction is a con) and self-help (therapy and homeopathy are, you guessed, a con). In the age of Brexit and Trump, this sounds dangerously vulgar and ugly. I did laugh, but the sound seemed to choke in my throat. Art is a play that encourages people to have contempt for intellectuals, experts, culture.

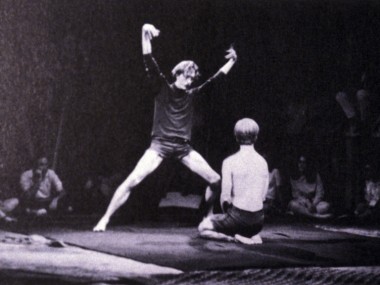

On the other hand, there is much to enjoy in Warchus’s production, which has a great sense of timing, and his cast is very strong: Sewell’s Serge has a thoughtful, husky impishness; when delighted he does a little dance. Ritter’s manic, finger-snapping Marc and Key’s tactful but brittle Ivan both explore the wilder shores of anger. At some moments, the actors mirror each other’s gestures. In fact, the chief pleasure of this production is the evident joy of the performers. And there are some high points: Key’s fast-paced monologue about his family and his prospective in-laws gets a deserved round of applause. More bathetically, there’s a fun sequence when the ping of olive pips in a metal ashtray humorously punctuates their exhausted chat. Although Mark Thompson’s design makes the homes of all three characters look like some anodyne hotel lobby, sophisticated but cold, Hugh Vanstone’s excellent lighting echoes the stripes of the painting at the centre of the play.

But although Warchus clearly shows the men’s shifting alliances, their touchiness and their needling, their jealousies and antagonism, the play remains a thoroughly conservative piece of writing. Also, Warchus — in his role as artistic director — is surely responsible for the neon sign that hangs above the entrance to the auditorium. It prods us to “dare”, which is very odd for a show that is so safe. The casting is conservative, the play is conservative and so is the production. Can I suggest an alternative slogan? Something like “Dare to be safe”?

© Aleks Sierz