Betrayal, Harold Pinter Theatre

Thursday 14th March 2019

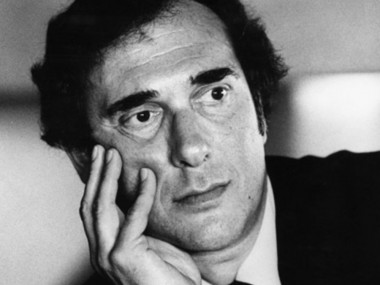

Tom Hiddleston. What can I say? His career has sprinkled handfuls of star dust from the very beginning: he won a best newcomer Olivier award for his part in Cymbeline in 2007, and his appearances in almost any classical play — from Ivanov to Coriolanus — have been greeted with wild cheers. On film, he’s been Loki in the Thor series, as well as livening up Steven Spielberg’s War Horse, and trying in vain to save a dreadful film version of The Deep Blue Sea. More recently, I loved his performances in Crimson Peak and High Rise. On the BBC, he was outstanding in The Night Manager. But how does he manage in Pinterworld?

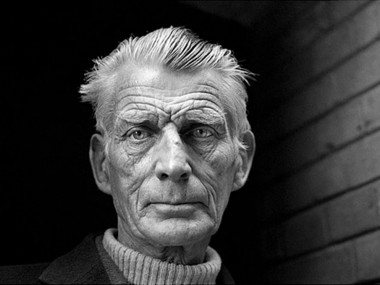

The situations created by Harold Pinter have a distinct linguistic and dramatic flavor, although Betrayal, first staged in 1978, is quite different in verbal style from the early comedies of menace. Okay, there are some pauses and repeats so characteristic of the master, but there is less ambiguity and more directness. It’s a much more accessible play. Although some scenes, not all by any means, run in reverse order, the story is quite clear. It’s basically a love triangle between Robert (Hiddleston), a successful London publisher, his wife Emma, who runs an art gallery, and his best friend, Jerry, a literary agent.

Starting with a moment in which Jerry, who is very drunk at a party held in Robert’s house, surprises Emma in her bedroom, and tells her he loves her, the play shows how their affair develops, with the illicit couple getting a flat in unfashionable Kilburn and meeting in the afternoons, then returning to their families, complete with kids, for the rest of the time. Although this is loosely based on Pinter’s own affair with Joan Bakewell, he tells it in a non-linear way, beginning with the break up and then moving backwards, in fits and starts, and he keeps circumstantial detail down to the bare minimum.

So although the world of the rich and privileged literary London is evoked through boozy lunches, jokes about authors and holidays in Venice, there is nothing — except perhaps the lack of mobile phones — that limits the action to the 1970s. Instead, this is a modernistic and minimalist play about men, masculinity and infidelity. All the characters are in their late 30s, and Pinter creates a dreamy kind of world in which civilized chatter about a fictional novelist called Casey, the poetry of WB Yeats, beers in the pub, and crockery and curtains and a table cloth from Torcello, all barely cover a subtext of erotic desire and passionate anger.

The central theme is of course betrayal, and the quick revelations about who cheated on whom, and when, in the first two scenes are both punchy and humorous. As is typical in Pinter, this is a story about male friendship, about boys together. The infidelity of the woman seems to matter less than the way the men feel cheated on by each other. Here the love triangle is all about how Jerry and Robert value their friendship more than they rate their intimacy with Emma. In one classic passage, about bonding over a competitive game of squash, Robert says, “To be brutally honest, we wouldn’t actually want a woman around.”

By telling the story in a non-linear way, Pinter emphasizes the importance of memory, of our reminiscences of past moments when we felt love, or desire, or experienced the glow of being fully alive. Jerry, for example, remembers throwing Emma’s child Charlotte into the air, while everyone was standing around laughing, as just such an occasion. Yet the irony introduced by Pinter is that neither he nor Emma are quite sure in which of the two families’ kitchen this incident took place. They disagree about it. Memory, of course, is malleable. It changes as our feelings change.

There is also a sense in Betrayal that the meaning is about much more than adultery. Emma, Jerry and Robert betray not only their spouses, but also the other members of their families, including Judith, Jerry’s offstage wife. Not to mention their rapidly growing children. And, in Pinter’s rather cynical and astringent view of literary celebrity, there’s a clear feeling that these bookish and arty types are not being true to either their own creative potential, nor to the expectations of the cultural world they inhabit. Personal potential and individual hopes join marital fidelity in a massive scrapheap. No one is able to be their better selves.

Following his highly successful season of Pinter shorts, called Pinter at the Pinter, director and producer Jamie Lloyd stages this masterpiece of a play with enormous intelligence and emotional energy. First, Soutra Gilmour’s design is a completely bare stage, coloured pastel greys, and with only a couple of wooden chairs and a card table for props. In almost every scene, the third person in this love triangle is present, standing at the back, leaning on a wall, staring at their hands. In this dreamy non-place we have to imagine the real-life setting, and we are made to remember that the cheated spouse is ever present in the minds of the deceivers.

Lloyd also adds some appealing flourishes by using theatrical technology: the back wall of the set moves forward, increasing the claustrophobic feel of some key scenes; the revolve spins at various speeds as the characters orbit each other’s lives; an onstage child is thrown in the air, embraced and held tight. None of this is strictly necessary, but it all adds to dynamic sense of rapid storytelling. Lloyd also dispenses with an interval, which is a good move and one which allows the psychological tensions to build uninterrupted during the 90 minutes of running time.

With this minimalist staging, the emphasis falls fairly and squarely on the shoulders of the actors. I always knew that Hiddleston could act, but his performance here is literally amazing: just as the dialogues barely hold down a volcanic subtext of agonized emotion so he never lets you forget that he’s hurting badly and that he’s capable of violence: whether on the squash court or in the bedroom. Or in public. In the otherwise comic restaurant scene, he stabs at his food with barely repressed viciousness. Yet when he discovers proof of Emma’s infidelity, he has the crumpled stare of a grown man about to howl in pain and lash out in rage.

By contrast, Charlie Cox’s Jerry is milder, more socially smooth — as befits his role as literary go-between and seducer — and Zawe Ashton calmly throws off the elegant cool that has often been her character’s main trait. Here she is openly skittish, sensual and unable to conceal any emotion except for dread. Hers is the most contemporary of the readings, in behaviour she is all very 2010s rather 1970s, and thus the female point of view comes across strongly and clearly in a play that threatens to sink under its masculinist assumptions. With its crystalline psychological detail and chic minimal staging, this is by far the best revival of this play that I have ever seen. Satisfaction guaranteed.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times