Between Riverside and Crazy, Hampstead Theatre

Tuesday 21st May 2024

It’s often said that contemporary American playwrights are too polite, too afraid of giving offence. But this accusation can’t be levelled at Stephen Adly Guirgis, whose dramas — from Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train in 2002 to The Motherfucker with the Hat in 2011 — are dirty-tongued and often fiercely emotional. As well as fearless. Now his Pulitzer-Prize-winning play, Between Riverside and Crazy — which opened Off-Broadway in 2014 and has also won other prestigious awards — comes to the Hampstead Theatre in a production directed by Michael Longhurst, a longtime fan of the playwright, and with a cast headed by the excellent Danny Sapani. Advertised as a Rabelaisian tragicomedy, what’s it all about?

Set in an apartment on New York’s Upper West Side, the story focuses on Walter “Pops” Washington (whose name is symbolic of his role in this state of the union drama), a widowed black ex-cop (Sapani). He’s lived in this Riverside Drive apartment for some 35 years, and his heavy drinking is not only down to the recent death of his wife, but also due to his long fight for compensation from the NYPD after he was shot and made impotent eight years before by a white officer. Meanwhile his rent-controlled haven is home to his son Junior, a smalltime criminal, and Junior’s scatty girlfriend Lulu, as well as passing temporary tenants such as Oswaldo, an addict in recovery.

This community of the hurt and harmed is represented with enormous verbal flair and the Rabelaisian exchanges are both vivid and comic. The heart of the plot is Walter’s desire to pursue his lawsuit against the NYPD, a Quixotic project which Detective Audrey, his former police partner, and her husband-to-be Lieutenant Dave try and argue him out of. Take what the cops are offering, and drop the lawsuit, they argue, bringing up the uncomfortable fact that Walter’s behaviour on the night of the shooting may have contributed to the incident, while Walter insists that the white cop was a racist and used the N word as he emptied his revolver into his black victim.

I really like the passionate discussion of race, one of the most highly emotional on the London stage at the moment, especially since both Audrey and Dave are white. The heated talk about a white cop shooting a black man (Walter was off duty at the time) feels very uncomfortable after the killing of George Floyd, and your attitude to this powerfully written conflict (was Walter in some way culpable?) will probably depend as much on your race as on your politics. Either way, it feels fully dramatized, lighting up the stage in the first part of the show, and then being reprised in the second. As well as being direct and emotionally true, Guirgis’s writing here has shades of ancient Greek tragedy, when there is no correct way to behave and all options are flawed.

The second half of the evening introduces the Church Lady, a Brazilian magic-realist character, who visits Walter in order to bring him communion, and maybe some chance of salvation. As she weaves the charm of her spell, with distinct shades of Guirgis’s chief inspiration (main man Tennessee Williams), there’s a miraculous sense of the possibility of change, of transformation. Yes, God might, just might, glance down kindly on this bitter patriarch, this father figure of the damned and distressed. Although it might help if Walter listened a bit more to his own son Junior, and raged a bit less in his daily drunken binges.

One of the pleasures of Between Riverside and Crazy is the not only the rust-flecked and raucous humour of the dialogues, and the general tragicomic vibe, but also its picture of the nation seen from the perspective of appealingly, if not necessarily realistically, drawn bad boys and bad girls, outcasts, losers, the lowly and the lonesome — a cracked republic of multicultural working-class diversity. Like so many American Dream plays this one has the nightmarish glare of violence, but also bright shafts of sunny optimism. In the end, argues Guirgis, we all have the chance to be free, of our demons and of other people. At the same time, this is a nation built on the idea of the deal.

In its second half, the drama takes an incisive, subtly farcical, look at this kind of Trumpian ideal of the deal — and shows how any bargaining is really a game of poker. Such insights are written with such vigour and such energy that they make up for some of the show’s failings. Yes, some characters are underdeveloped; yes, some themes, especially that of fatherhood, are undernourished; yes, some passages are too explanatory. But, really, in the end, who cares? Isn’t a flawed play about flawed individuals just right? And any faults are overcome by the sheer joy of the playwriting, the eccentricity of the characters and the frank emotionality of the conflicts.

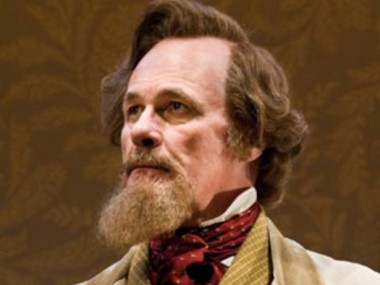

Longhurst’s production, designed by Max Jones, carefully balances the rhythms of a first half which is naturalistic and impassioned with a second one which is more dreamlike, even a bit humorously surreal. The performances are strong across the board: Sapani connects well with Walter’s fury, and also with his frustrations and sadness, at times underlining the humour with a twitch of the eyebrow or a deprecatory hand gesture. Martins Imhangbe’s Junior and newcomer Tiffany Gray’s Lulu are as excellent as the rest: Sebastian Orozco’s Oswaldo, Judith Roddy’s Audrey, Daniel Lapaine’s Dave and Ayesha Antoine’s scene-stealing Church Lady. All contribute to a muscular piece of Americana.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk