Bitter Wheat, Garrick Theatre

Wednesday 19th June 2019

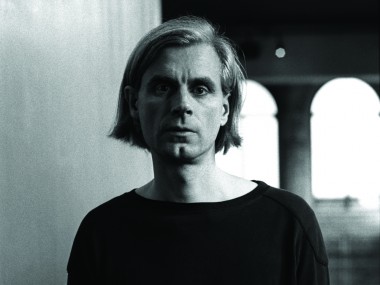

John Malkovich is back in town — and he’s starring in the most controversial play of the year. Trouble is, it might well also be the worst. When the subject of veteran American playwright David Mamet’s new drama was announced as being about a Hollywood mogul, who, like Harvey Weinstein, is accused of abusive behaviour towards young women there was a predictable outcry. How dare Mamet write about this? How dare a man write about sexual abuse? How dare fiction trespass on fact? Although the Garrick Theatre in the West End was besieged by autograph hunters rather than protesters at tonight’s press night, twitter has been alive with rumours for months. But apart from the outrage, what is the play actually about, and is Malkovich, in his first London appearance for some three decades, any good?

Malkovich plays Barney Fein, a Hollywood producer, who is at first presented as an outrageous potty mouth, a reptile who snarls and sneers at his own entourage. His power is shown in his vicious verbal assaults on a hapless writer, whose script he despises, and in his manic ability to bribe all and sundry to give him their votes in an upcoming award. As a nod to his humanity he also has an aged mother, sick with cancer, and about to celebrate her birthday. Of course, helped by Sondra, his personal assistant, and his pill-providing doctor, he also has sexual needs. Which he plans to indulge with the help of Viagra and Yung Kim Li, a young Anglo-South Korean actor, who has just flown in from Seoul.

Fein’s seduction technique involves a two-pronged attack: on the one hand, he displays an arrogance of power; on the other, he whines self-pityingly about being overweight. But this is less a study of body dysmorphia, than a series of jokes about toxic masculinity as Mamet gives Fein the lion’s share of the lines. Rude and vile, he declares that “humans are animals” before making crass digs about Jews, Koreans and Chinese. If the intention is to make us hate this guy, then this is a great success; if laughs are wanted, then this material falls flat. For light relief, Fein fiddles with his zip. When he’s with Yung Kim Li he promises to promote her film, Dark Water, which he then suggests could be better called Bitter Wheat.

Mamet fans will know that Hollywood is familiar territory, memorably visited in his 1988 play, Speed-the-Plow, where in his imagination male sharks swallow any female minnows that swim their way. Nor is the playwright any stranger to controversy. Ever since his 1992 play, Oleanna, divided audiences with its portrayal of a confident male professor facing a confused female student there have been questions about Mamet’s lack of sympathy for his women characters. After all, much of his most celebrated work is a feast of testosterone-heavy masculinity: the world, he seems to imply, well it’s a place for men. Women are just walk-ons. And so it remains. Bitter Wheat, which is advertised without a trace of irony as the Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwright’s response to the #MeToo movement, is one long male monologue.

In fact, Bitter Wheat is a classic of lazy playwriting. Mamet follows a simple recipe, writing by numbers. And you could do this too. Here’s how: 1) Select a current controversy; 2) Read a couple of Sunday supplement articles about it; 3) Dredge your memory for some Tinseltown anecdotes; 3) Write a monologue. Add jokes. (The biggest laugh on press night was the line: “Tell my children that their mother is a cunt.”) How witty. How subtle. What is so annoying is the vacuity of the result. With no plot or drama to fill the running time, it really is an achievement to write a piece that has so little to say about Weinstein, about Hollywood, about life, about women, about sex. And then to spin it out over two hours.

Occasionally, very occasionally, there’s a sharp putdown or a funny line. When Fein mocks the writer of the “shit” screenplay, the penman puts a curse on him. In reply, the producer coos: “Use your words to wound me — I’m gonna cry all the way to the heliport.” Fein hates his mother, but claims to support good causes, and once or twice voices liberal views. At moments like this, you do wonder what has happened to this play, which could have been that fabled creature: a right-wing drama. But it’s not, and never even tries to be. As well as jokes about the Writer’s Guild drinking “a beaker of my mucus” and some silliness about Imelda Marcos’s bejeweled copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, the story loses its way amid repeated “fat” jokes and a second half that becomes increasingly surreal as first a corrections officer and then a terrorist are stapled to the plot.

Malkovich, who I last saw as Hercule Poirot in the BBC’s Christmas Christie (aka The ABC Murders), makes the most of his grizzled seniority, and his voice has a familiar melodic range, which he occasionally uses, soaring and swooping in this portrayal of a character whose whole life is actually an act, the producer as performer. You can see small joys in this thespian masterclass, but it’s not enough. As directed by Mamet, Malkovich dominates the stage as a cut-price Falstaff, lending a peculiar humour to his corpulence, a joke that is endlessly emphasized. At times his performance is fun; at times it’s funny; over time, it’s a bore. Much of his acting is off-hand. What’s missing is any sense of real threat; even fans might feel shortchanged.

On Christopher Oram’s bright set, which features a lamp stand made of a gold-plated Kalashnikov, Malkovich’s Fein is like a child in a playground: he never stops talking, never stops being the centre of attention. Because the play is one long monologue, none of the other actors have much chance to shine. Doon Mackichan’s Sondra and newcomer Ioanna Kimbook’s Yung Kim Li get a few lines, with the latter even able to articulate some notes of protest, but both are drowned out by the monstrous Fein. His key line is “I’m talking about myself”, and boy does he mean it. Implausible, poorly written, gratuitously offensive, daft and irritating, Bitter Wheat leaves a very bad taste.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk