Blue Surge, Finborough Theatre

Thursday 4th August 2011

Rebecca Gilman is an American playwright who once made a big splash in London. After having work such as The Glory of Living, Spinning into Butter, Boy Gets Girl and The Sweetest Swing in Baseball staged at the Royal Court in the first five years of the new millennium, she then disappeared from view. Now she’s back in the capital with a 2001 play, whose UK premiere opened tonight and which takes a peek at some close relationships between cops and hookers in a small Midwest town.

Somewhere along Route 29 is a little whorehouse called Naughty But Nice (yes, really). Two of the teens working there, Sandy and Heather, also share an apartment. One day, prompted by a Christian pressure group, two cops — Curt and Doug — try, with laughable results, to raid the joint. Naively enough, their encounter with the young prostitutes fires up their testosterone, lights up their imaginations, and soon Doug hooks up with Heather while Curt falls for Sandy. Doug’s desires are pretty basic, as his jokes about anal sex make clear. By contrast, Curt is a more complex case. Although his fiancée Beth is a nice, upper-middle-class artist, he can’t really bond with her; his background is working class, which partly explains why he instantly hits it off with Sandy, whose background is similarly and predictably chaotic. At first, Curt’s interest in her is quite noble: he sympathises with her, he likes her, he wants to help her. But very soon his heart begins to rule his head.

This a play in which the American Dream suffers an eclipse, caused by the reality of poverty, although the sun of optimism occasionally peeks out, its rays inspiring a sense of heroic individualism that warms the troubled men. In this bleak landscape, the men are wounded, jealous, prone to sudden violence, discontented. The women might be more varied psychologically, but they are also seen as lost souls. Both sexes are aware of dissatisfaction and grope blindly for meaning and purpose.

The plight of Sandy and Curt receives Gilman’s most sustained attention, with Sandy’s various attempts to leave her squalid lifestyle behind sympathetically portrayed. What eventually happens to both of these people, however, suggests that class is destiny — broken homes create broken lives. Like, for ever. The men become losers, the women whores. In this darkness, there is little hope for change, only brief moments of human consolation.

I must admit that I’ve never really liked Gilman’s writing style. It’s too explicit for me: every dialogue means what it says; everything is straightforward; every symbol is explained. This time, despite its subject matter, Gilman’s play never really gets down and dirty; it never cuts sharply to the bone; it always keeps its undies on. It is too polite for its own good. It’s too clean for its subject matter. Even the central debate on class origins — “where you come from is not who you are” — never quite comes alive. Sure, Gilman has a lot of empathy for her characters, but somehow you seldom feel that you can glimpse their emotional core.

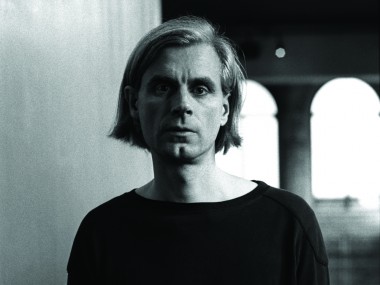

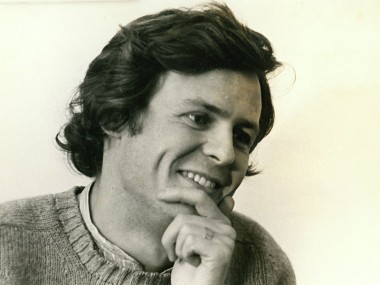

Still, Blue Surge (the title comes from a mishearing of the moody Duke Ellington song “Blue Serge”) has interesting themes and plenty of humorous lines. In Ché Walker’s enjoyable production, with its excellent soundtrack and economic set, James Hillier turns in a powerful performance as Curt and Clare Latham successfully explores Sandy’s path to self-knowledge. Equally watchable are Alexander Guiney as Doug, Kelly Burke as Heather and Samantha Coughlan as Beth. But when a writer always seems to be holding herself back, the evening feels curiously restrained and is only really touching in the quiet final scene. By then it is just a bit too late to care.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk