Changing Destiny, Young Vic

Friday 30th July 2021

The Young Vic, led by the inspiring figure of Kwame Kwei-Armah, is back. After a prolonged closure, during which this venue has passionately continued to work with young directors, the local community (including both delivering food and creative engagement) and the Black Lives Matter movement, the main stage now reopens with Booker Prize winner Ben Okri’s short play, Changing Destiny, directed by Kwei-Armah. Based on a 4,000-year-old poem from ancient Egypt called Sinuhe, the story is one of political intrigue, fearful exile and then spiritual rebirth. At a time of increasing rhetoric and anxiety about migration, the piece shines with relevance, but does it work as drama?

The tale begins with Sinuhe, a youthful soldier in the Egyptian Royal Guard, who one day finds himself among conspirators who want to replace their leader, the Pharaoh Amenenhet. Because he is torn between his loyalty to authority and his consciousness of its corruption, he is unsure what to do. The Pharaoh is a god and to kill a god is to kill your soul. After fighting in Libya with San-Usert, the second most powerful man in Egypt, Sinuhe learns that the Pharaoh has been assassinated and that San-Usert is to succeed him. Although he was never a conspirator, Sinuhe suffers from a guilty conscience and goes into exile, in the process being separated from his spirit, becoming half a man.

Fleeing into a desert, and suffering in the burning wilderness, Sinuhe finally arrives in Syria. At first he is only able to find work as a servant for a Sheik, and is treated with suspicion, but — after many adventures in Libya and other lands, during which he makes an advantageous marriage to Hotemi, a king’s daughter — he gradually becomes that mythical figure: the foreigner who inherits a kingdom. After dealing with Denshi, a royal adviser who turns traitor, Hotemi urges Sinuhe to return to Egypt. So, after almost 30 years, he is back in his homeland, but can he master the guilt he has felt and be reunited with his spirit self? Of course he can. It’s a myth after all. So Sinuhe finally fulfills his destiny in a changing world, teaching us the lesson that Africa is the “initiation chamber for future civilisations” and that we should all “activate the full dimensions of the human spirit”.

Okri’s text has a light and lithe quality, and its politics are not only those of exile, homesickness and welcome, but also more widely of a reclaiming of ancient Egyptian culture as a black African identity. As he writes in the programme, instead of trying to “separate ancient Egypt from Africa”, we should try to see this ancient civilization as, like Mesopotamia, a cradle of world myth. Sinuhe the poem is about “identity, immigration, social disorder, the mystery of power, changing fortunes, and the inexplicability of the deep motives of our actions”. Seen like this, the forgotten masterpiece of the Middle Kingdom foreshadows not only Hamlet, but also Oedipus Rex and The Odyssey, and one episode anticipates the struggle of David against Goliath.

While the meaning of Changing Destiny, with its confidence in black pride and its hugely mythical range, is never in doubt, your enjoyment of the piece is directly related to how much you value ancient mythology. I must confess that usually I have little patience with these far off fables of epic journeys and man gods, of terrific battles and stupendous riches, and anyway I felt more than once that Okri’s text would work better if read rather than narrated. Characterisation is thin and too much is superficial and didactic. But, maybe for the Game of Thrones generation, this is less of an obstacle to the experience of a unique and genuinely new literary discovery. For me, it is just a bit too educational to be truly pleasurable.

Nevertheless, I really appreciate the theatrical finesse that Kwei-Armah has brought to his staging. Using a bare open space, dominated by a pyramid tent which mirrors the firmament above, and then opens out, this is theatre that needs only a few basic props to evoke the clash of huge armies, the majesty of ancient kingdoms and the solitary wanderings of the hero. At several moments, I was reminded of an Egyptian show that I once saw, three decades ago, in a Cairo tent, where the closeness of the actors to the audience and the integrity of the acting conveyed a similarly epic story. Kwei-Armah’s staging honours beautifully this connection between London theatre and the wider world.

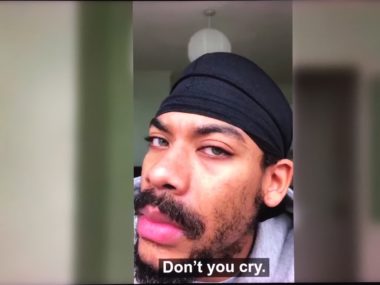

Using only two actors — Joan Iyiola and Ashley Zhangazha — the 65-minute production has an exciting pace and some vivid moments. Designed by David Adjaye, with projections by Duncan McLean, and music by Tunde Jegede and XANA, this show begins with Iyiola and Zhangazha playing “rock paper scissors” to decide who will be Sinuhe. On the night I went, it was Iyiola, and her portrayal is instantly appealing in its clarity and charm. Likewise, Zhangazha takes on all the other characters with enormous energy. Both turn in passionate and engaging performances. If by the end I never really felt that I had connected deeply enough with Sinuhe, maybe that says more about me than about Okri and Kwei-Armah’s adventure in mythic storytelling. Even though it left me cold, the theatricality of this show might change someone else’s destiny. Who knows?

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk