Chimerica, Almeida Theatre

Friday 24th May 2013

In my book on contemporary new writing for the British theatre, Rewriting the Nation, I remember complaining about the narrow vision of most young playwrights: “Over the decade, there were plenty of British plays about the War on Terror but none about the rise of China. South American was of no interest to playwrights. Politically, the world of 2000s British drama was a curiously shrunken place.” Of course, it was only a matter of time before someone would come along to decisively challenge this accusation of insularity. So it goes, and now it’s happened. Her name is Lucy Kirkwood and the play is Chimerica.

From the start, it is a winner. Remember the image of the lone activist standing in front of a tank at the climax of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989? A symbol of resistance against impossible odds, and an example of almost reckless individual bravery. But what happened to the young man? Was he shot by the Chinese army, or did he survive? In the play, Kirkwood creates an imaginative epic journey for a fictional American photographer, Joe Schofield, who once snapped a career-defining picture of the “tank man” and has now heard that the young protestor is alive and living in the United States.

Joe’s quest takes him through the Chinese community in the land of the free while in Beijing, his contact, Zhang Lin, engages with his own struggle against the authorities. Angered because his 59-year-old neighbour has died due to poisoning by air pollution, Zhang Lin tells Joe the story. But this results in his being arrested and tortured, and being disowned by his brother, a factory manager who is too scared to support such a quixotic protest. Meanwhile, Joe comes into conflict with his newspaper boss, his friends and his lover, a market researcher from England.

The play’s title, a neologism coined by historian Niall Ferguson and economist Moritz Schularick, describes the symbiotic, and toxic, relationship between the two new superpowers, China and America, in the wake of the end of the Cold War in 1989. Too much saving in China and too much spending in America caused, they argue, the global financial meltdown of 2008. But Kirkwood’s play is not a political documentary; it’s a rather tragic story of humans caught in two very different cultural binds. In America, the individual is free to pursue any mission they like — just as long as there is a market for it. So Joe’s conflict with his boss shows up the limits of his freedom. Likewise, in China, the individual is free to participate in the market — just as long as they don’t question the authorities. So Zhang Lin pays the price for rocking the collectivist boat.

What’s dazzling about Chimerica is that these individual stories are played out against the background of huge issues: the American Presidential election of 2012 and the growth in horrendous air pollution in China. As the play jumps between these two countries, and between 1989 and the present, a host of other issues, from the cultural politics of representation to the personal politics of friendship, come vaulting across the stage.

In Lyndsey Turner’s superb production, with its excellent cube design by Es Devlin, the scenes unfold cinematically with projections of monochrome photo contact sheets, marked by an editor’s red pen, a constant reminder of both artistic and political censorship. In this context, all individual struggle requires the toughness of heroism, and more than a touch of luck. What are the ethics of photojournalist? What are the responsibilities of activists? Does every picture really tell a story that is worth more than a thousand words?

The show is so dazzling and fast-moving that these big questions occur to your mind in a fleet-footed and almost subliminal way. I loved the sheer drive of the narrative, which means that the three hours of running time never drag, and that new ideas spring from almost every scene. Kirkwood apparently spent some six years writing the play, which she has turned into something of a gripping thrill machine, as efficient in telling its interlocking stories as the cube set is in turning. Above all else, the image of China — a country which may have “gone from famine to Slim-Fast in one generation” but which “values the supremacy of its own culture above all else” — stays with you after the end of the show.

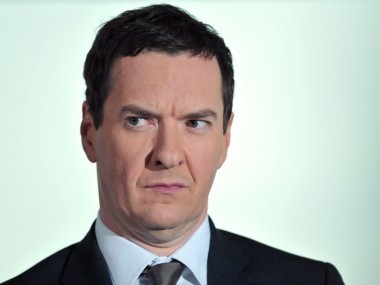

A co-production between the Almeida and Headlong theatre company, the large cast is full of impressive performances, led by Stephen Campbell Moore as Joe and Benedict Wong as Zhang Lin, with appealing contributions from Claudie Blakley as Joe’s girlfriend Tessa, Trevor Cooper as his editor and Sean Gilder as his journo colleague. Even seeing the show in preview, when it wasn’t quite ready, I have the distinct impression that this might be one of the very best plays of the year.

© Aleks Sierz