Choir Boy, Royal Court

Monday 10th September 2012

With the American presidential election campaign now in full swing, the search is surely on for cultural expressions of the two nations that the candidates represent: white rich people versus the rest. Okay, maybe an exaggeration, but who says I’m unbiased? Anyway, a new play from Tarell Alvin McCraney, one of the most innovative black American playwrights of his generation, runs the risk of being seen as a metaphor for Obama’s first term in office. But does this burden the new play with too many expectations? At first sight, maybe so. The setting is the Charles R Drew Prep School for Boys, an all-male and all-black high school which is immensely proud of its 50-year tradition of choir-singing. In this hothouse, a conflict rapidly develops between the effeminate and talented Pharus, who wants to be the best choir leader ever, and Bobby, a much more hetero type. In their power struggle, Bobby is aided by the fact that he is Headmaster Marrow’s nephew; Pharus is aided by his own sharp wits.

The other boys are a mixed bunch. There’s AJ, who is Pharus’s loyal room-mate, and David, who wants to be a pastor. Then there’s Bobby’s sidekick, Junior. All of them are members of the school choir. But Headmaster Marrow also widens the play’s debate by inviting an older white professor, Pendleton, who is a veteran of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, to come and teach the boys to reason critically.

When the conflict between Pharus and Bobby escalates, Headmaster Marrow and Pendleton both try different ways of mediating between them. In the process, a fascinating debate about black music and black history emerges. Bobby, for example, believes that traditional black spirituals were clandestine instructions designed to help slaves escape in the days when that institution held sway in the South. These songs held coded messages, designed to give details of the best way to avoid recapture if you were a runaway slave heading for the northern states. This idea is questioned by Pharus, who argues that runaways had no need for coded manuals passed down though songs and that the function of song is more directly to inspire though its own inherent musical beauty, and the grace of its words. In other words, Bobby’s view is an invented tradition and has no basis in fact. With this scene, McCraney’s play catches fire, and you can feel your pulse quicken.

But pleasure turns to dread as you soon realise that the sexual conflict between red-blooded heteros and the limp-wristed homos is about to turn violent. And, at the cruel heart of this violence is religious delusion. For doesn’t the Bible condemn homosexuality? Isn’t God’s purpose best served by rooting it out? And yet what happens to a young man when he calls on the Almighty to protect him from sexual desire, and gets nothing but silence as an answer? McCraney rides these white-water rapids with enormous confidence and verve, blending ideas about religion, music and history into an intoxicating mix.

Although by using a setting that is almost exclusively black, he focuses the discussion on the black community, it’s easy to see the wider thrust of his argument. For the black community, the criticism is that while it is proud of its emancipation from slavery, it is still shackled by Old Testament ideas about sexuality. For the wider community, the criticism is that slogans — such as Obama’s “Yes we can” — are often grounded in poor history and poorer reasoning. In both cases, human tenderness and kindness is our only succor.

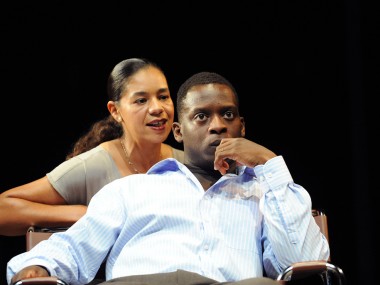

McCraney writes in a blank verse that in its vigour and moments of artifice conveys a lot of the emotional ambiguities of the story. Pharus — whose name recalls the gay hustler of McCraney’s American Trade — is ironical, subtle, manipulative and bitchy. In Dominic Cooke’s engaging production, he is beautifully played by newcomer Dominic Smith, whose knowing grin can turn instantly into a grimace of pain. He perfectly captures the contradictions of a young man who wants both to come out and to honour his school’s masculine ethos.

The rest of the youthful cast — Khali Best (AJ), Aron Julius (David), Eric Kofi Abrefa (Bobby) and Kwayedza Kureya (Junior) — sing brilliantly, and their acting is fresh and credible. As the school authorities, Gary McDonald is Headmaster Morrow and David Burke is the 1960s veteran Pendleton. Both excellent. Design by Ultz turns this venue’s studio theatre into a boarding school, deftly and confidently suggesting a public hall, classrooms, showers and a bedroom. At times, the audience feel like parents at Graduation Day. Yes, Choir Boy is much more than just a metaphor for Obama’s America — it’s a complex, stimulating play that touches the heart.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk