Crossing Jerusalem, Park Theatre

Friday 7th August 2015

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has not been very prominent in the news recently, but that doesn’t mean that it has gone away. As Julia Pascal’s 2003 play reminds us, religious and cultural tensions can go deep. Very deep. At the centre of her intense story, which is set over about 24 hours during the second intifada, is Jerusalem, a divided city, a contested territory, a place which it is dangerous to cross. As bombs explode in cafés and on buses, the events of the drama illustrate the tight embrace of the personal and the political.

Varda Kaufmann-Goldstein is an Israeli estate agent who is trying to raise a loan for a property deal. Her second husband, Sergei, a Russian Jewish immigrant, is stepfather to her two children, the haunted Gideon and his sister, the cheerfully promiscuous Lee. Both these youngsters have been called up by the military. The way the conflict has an impact on family life is immediately seen when Gideon and his wife Yael, who have a four-year-old daughter, quarrel about having another child. On Yael’s 30th birthday, as the play begins, the family plan to make the perilous journey across the city — through “bandit country” — to Sammy’s restaurant, a location which they used to frequent more often.

Run by a Christian Arab, this eatery is a meeting place for Jews and Muslims. Working for Sammy is Yusuf, whose 16-year-old brother Sharif is one of the youthful hotheads who is fighting Israeli troops, mainly by throwing stones, in the intifada. When the Kaufmann-Goldsteins arrive, at first the atmosphere is convivial enough, with Sammy and Sergei chatting about girls over chilled vodka, and the act of crossing Jerusalem seems for a moment to be a metaphor of hope. But as secrets from the family’s past emerge, the tangle of sex and aggression releases an unexpected violence.

The keynote of Crossing Jerusalem is complexity. Pascal has a real talent for imaging what all of her very different characters are thinking and feeling. The complications are deliberate: Yael’s mother comes from Algeria and her family speak Arabic better than Hebrew; Sergei is a Russian Jew who lost a son in Kabul during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan; Sammy is a Christian Arab who doesn’t hate Israelis; Yusuf wants to protect his younger brother, but also wants recompense for the injustices of the past.

These complexities result in a tough, knotty play that is much better at raising difficult questions than at providing any kind of answer. This may well represent the intractable reality of the Middle East, but it also means it is hard to satisfy an audience’s understandable thirst for a more decisive conclusion. In fact, the story does lose some focus towards its end, and despite its hectic humour, concludes on a gruelling and punishing note whose unrelieved horror and melodramatic sensibility is hard to take. But that difficulty is also just right for the subject matter.

The great thing about the play is that Pascal uses a breathtaking coincidence in order to engineer an ethical debate. Because the Kaufmann-Goldsteins have benefitted from receiving reparations from the German government for Nazi depredations, shouldn’t the Palestinian Arabs be similarly compensated for the loss of their land, for the restrictions on their civil liberties and for the exploitation of their labour? In a tense scene, these moral ideas are debated with passionate integrity. But, even if Yusuf and Sharif do succeed in getting some money, can they really escape from their heritage?

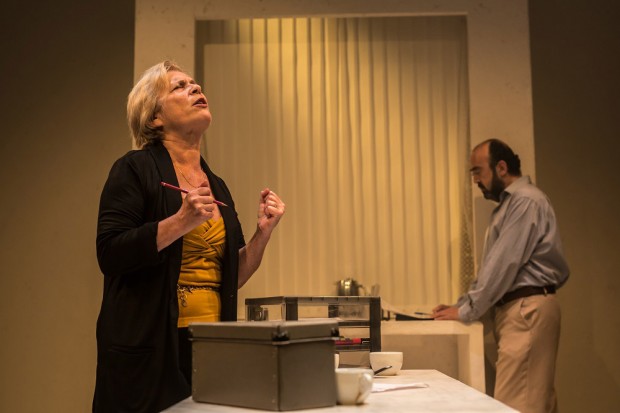

There is much to enjoy, especially in Pascal’s account of the tensions between sexuality and ethnicity, and her portraits of marriages suffering under the burden of silence is compelling and convincing. Likewise, the details of the military occupation are still shocking, even if they are depressingly familiar. Pascal’s own production, designed by Claire Lyth, doesn’t always elicit performances that sit on the right side of exaggeration, although her cast — led by Trudy Weiss (Varda), Chris Spyrides (Sergei) and Waleed Elgadi (Yusuf) — is strong. Sometimes funny, more often fraught, this is a powerful account of a complex issue. But Crossing Jerusalem cannot be described as an easy ride.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk