The Cutting of the Cloth, Southwark Playhouse

Tuesday 17th March 2015

Nowadays, playwrights do their apprenticeships at university, studying drama. But, once upon a time, they had proper jobs before they started making theatre. Such is the case of the late Michael Hastings, who died in 2011 and whose most famous piece is Tom & Viv (about TS Eliot and his wife). Before becoming a playwright, he worked for three years as a tailor’s apprentice. The Cutting of the Cloth, written in 1973 and accumulating dust in a bottom drawer ever since, is based on those early work experiences. But is it worth staging?

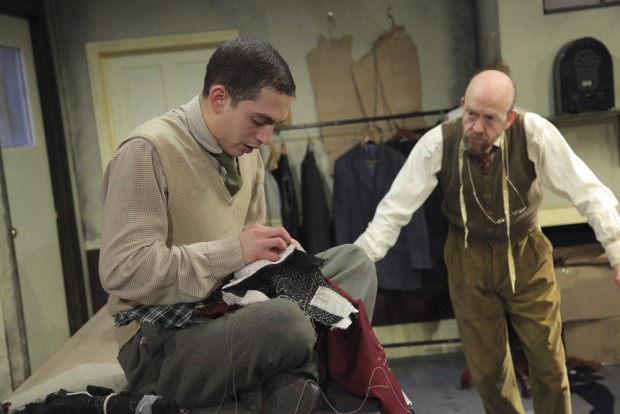

The story is set in Savile Row and takes place during just over a year between 1953 and 1955. In the cellar of a gentleman’s tailor is a chilly workshop where two craftsmen work long hours for little money. They are vividly contrasted: Polish-born and Jewish Spijak, a widower given to shouting, believes that hand-sewn suits are the mark of true craftsmanship; Eric, a Londoner and bachelor, uses a sewing machine to improve his productivity and his income. Both master craftsmen have female helpers — tailoresses called kippers (because they looked for work in pairs to avoid sexual harassment): the older Iris, who helps Eric, and the younger Sydie, who is Spijak’s daughter. Into this isolated world, with its own vocabulary and traditional work practices, comes Maurice, Spijak’s 16-year-old apprentice, who at first has aspirations to become a playwright. In one sense, this is a traditional 1970s work play; in another it is a family drama and a coming of age story; in yet another it is about the passing of an old way of life.

In the 1950s, the old way of tailoring — in which almost every seem of a suit was hand-stitched and the best suits were so well put together that they were, in Spijak’s words “invisible” (not loud) — was fast being overtaken by the new methods, which depend on sewing machines and speed. This is the faster, cheaper way of consumer capitalism. The hand-made suit must not only look good, but it must also advertise its quality. It must strut the walk, and talk the talk. As Hastings describes this big change — which is clearly also a metaphor for other changes in society — he also makes allusions to the wider society: at this time, future prime minister Harold Macmillan (of “You never had it so good” fame) is minister of housing, and he needs a tweed suit for a shooting party. Later in the play, a lot of work arrives from a contract with some Hollywood stars. But despite this social awareness, this is a story about people.

At the tragic heart of the piece is the figure of Spijak, a master craftsman and lone drinker, who sees a hand-sewn and perfectly tailored suit as man’s closest brush with heaven. If work demands a 14-hour day, then work will get 14 hours from him — even if it kills his wife (who was also Eric’s sister). In one moment of profound meditation, we learn that their love life was arid, for Spijak’s main desire is to excel at work. By the time Maurice arrives, he is known as “a bleeding tyrant”. For the teenager, the play begins in fear and trembling. Unspoken, although occasionally alluded to, is the whole history of European Jewry, with its generations of migrants to the East End. Maurice is not only the new boy, he is also a symbol of the new secular Jewishness.

The Cutting of the Cloth is a real drama of feeling. Not much happens over the duration of the evening, but a deep sense of real life being lived is evident and all of the characters are deftly drawn. The work is shown to be a process not only of craft, but also of pain, in which fingers are cut and blistered and calloused. As time passes, a sense of tragic inevitability grows, which, despite the humour of the writing, shades into an exquisite feeling of deep sadness. This is a wintry play for a cold night. If you can, sit under the air con.

It is also a real find. Discovered by Two’s Company, it is sensitively directed by Tricia Thorns on Alex Marker’s set, which is so realistic you can almost feel the loose threads tickle your nose. The cast is superb, with utterly convincing performances by Andy de la Tour (Spijak), Paul Rider (Eric), James El-Sharawy (Maurice), Alexis Caley (Sydie) and Abigail Thaw (Iris). Although I wasn’t entirely comfortable with the fact that one tearful moment was played for laughs, the show did convey a wonderful sense of a world and a sensibility we have lost. Yes, this feels like Zen and the art of tailoring — real craft, real quality, no rubbish.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk