Death of England: Closing Time, National Theatre

Saturday 23rd September 2023

It’s closing time somewhere in the East End. Nah, not the pub, but at a small local shop. Inside, Denise is banging around with some big pans, while Carly is packing up the flowers. Their business is coming to an end and they are about to hand over the keys to the next tenant. This is also the two-hander climax of Roy Williams and Clint Dyer’s epic Death of England tetralogy, which began in early 2020, and has been one of the best new writing series recently staged at the flagship National Theatre. But while earlier episodes — Death of England, Delroy and Face to Face — featured the men, this time it’s the turn of the women.

And what a formidable duo they are: strong-minded Denise Tomlin is a 56-year-old former nurse and qualified chef whose dream of running a West Indian eatery has just been destroyed by mouthy Carly Fletcher, 36-year-old daughter of a florist and her current business partner. But their collaboration has, from the start, been affected by twisted family ties. Carly is the longtime girlfriend of Denise’s son Delroy, whose best mate since childhood has been Michael, Carly’s brother. Although Closing Time has references to the various tensions between these people, it helps to know that Alan (Michael and Carly’s father) was a racist bigot and that both Michael and Delroy have, in the previous plays, delivered powerfully passionate monologues about how they feel about race.

This time, while Michael and Delroy are away watching their team — Leyton Orient — playing a match against Manchester United, it’s the women who are working, cleaning up the shop, packing up their stock, and closing down their business. At first the focus is on Denise, her ambitious hopes, her thoughts about her son Delroy, and her exasperation that men put so much energy into watching sport when they do so much less, emotionally, nearer to home. Then, in a monologue which mixes desire and laughter, Carly tells the cracking story of how she and Delroy got together. Riffing on Roxy Music’s “Avalon” — “Yes, the picture’s changing every moment” — the playwrights also remind us that Carly and Delroy have a daughter, Megan, a mixed-race child whose existence suggests a ray of hope for the future.

While watching the king’s coronation, Denise has a kind of epiphany about Carly, who is part of her family now, but paradoxically is both close and distant: “She knew us but still wasn’t us.” It’s a phrase that grasps some of the harsh truths of Williams and Dyer’s complex view of race. They powerfully show some of contradictions and tensions in the lives of both women, and are alive to the — occasionally savage — emotional swings and roundabouts. But as well as truth-telling, there is plenty of humour, from jokes about patois to a remark that the Royals have more trouble with a mixed marriage than the Tomlins and the Fletchers. Pointedly, Denise calls Carly her “daughter in sin”, rather than in law.

As you’d expect, the play’s text is a bubbling, splatting, hissing brew of love, hate, resentment and truth. As in the previous plays, the structure is fragmented, switching from dialogues to monologues, giving the characters space to explore their feelings and to air their thoughts. Williams and Dyer let them go off on tangents and make subtle allusions, as you would in real life, to shared stories and situations. There is a highly charged, often jagged feel to many passages and this ragged sense of words freshly articulated is brilliant, better — in my mind at least — than more polished writing, but often just as poetic. It’s fresh, and real. And passionately and abundantly alive.

It is also a dramaturgically exciting play, with one episode, when Carly entertains her girlfriends in a limo on a hen night, which seems to me to be guaranteed to illustrate with punchy theatricality some of the perceptive points being made verbally, intellectually. Unless I am mistaken, this episode — which I won’t spoil plot wise — is likely to become an instant contemporary classic about race in Britain. It is one of those moments which I imagine will be experienced differently by audience members, depending on their skin colour. Like so much in this drama it is controversial and thought-provoking. Taboos will be broken.

Across five vibrant scenes, which never slacken, Death of England: Closing Time explores not only the complicated feelings of mixed-race families, but also the way the monarchy perpetuates the history of imperialism, the glory-seeking of the football fan, social media cancel culture, and the consolations of music, and food, and haircuts. Plus of course the irrationality of desire and the sadness of remembering dead fathers. With language that includes phrases such “makes your piss boil”, “nipples a buss tru your blouse” and “men with an IQ the size of their dick in inches”, such themes are never dry. They come across as tear-spattered and sweat-soaked — as I say, thrillingly alive.

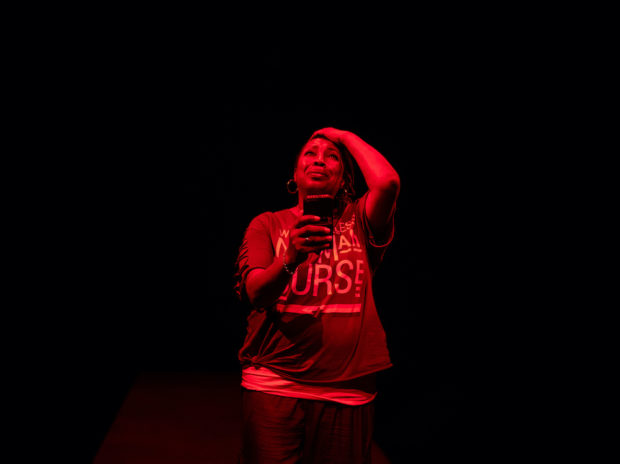

As in previous episodes of this family saga, Dyer directs the show — designed by Sadeysa Geenaway-Bailey and Ultz — with enormous precision on a stage whose cross shape is occasionally lit red to remind us of the flag of St George. Jo Martin’s Denise has a strong stage presence, both dignified and furious, with a vividly rasping delivery of putdowns and comments, while Hayley Squires’s Carly buzzes around with the febrile energy of a woman still — like her brother — unable to control her mouth. Both actors plug straight into the sizzling mains socket of the electric text, both are equally vulnerable as well as angry. As before, the offstage characters — such as Alan, Michael, Delroy and Megan — are represented by items such a Sun newspaper or a framed picture. Their psychological presence is constant. This is tremendous new writing about a business closing, but it’s also a story about hearts opening.

Since reviewing the production, Jo Martin has been indisposed. The role of Denise is now performed by Sharon Duncan-Brewster.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk