Detaining Justice, Tricycle Theatre

Monday 30th November 2009

The plight of asylum-seekers is no laughing matter, but that doesn’t mean that dramas about the subject have to be worthy, or dull. In fact, young playwright Bola Agbaje’s Detaining Justice, which opened tonight, is an exemplary mix of laughter and tears. As the final part of the Tricycle Theatre’s trilogy — the Not Black and White season — examining the state of the nation at the end of the new millennium’s first decade, this play confirms the feeling that much of the energy in new writing is now coming from black writers.

Earlier episodes in the trilogy were Roy Williams’s Category B, a powerful and realistic drama about life in a prison, and Kwame Kwei-Armah’s Seize the Day, which dared to imagine a black candidate in the running for London mayor. Both are still in rep, and a mixed-race resident company of actors enable the audience to see the same performers playing different characters on different days in these very different plays.

Agbaje’s story focuses on Justice, a young political activist who has fled Zimbabwe. Although his sister Grace, who came to Britain before him, has been successful in her application for asylum, he has been incarcerated as an illegal immigrant. When a maverick lawyer, Mark Cole, takes up Justice’s case, the outcome is even more uncertain — at first, Cole looks as if he doesn’t really deserve his reputation as a legal wizard.

With a fairly large cast at her disposal, Agbaje is able to put Justice’s story in a wider context, bringing in Pra, a preacher whose evangelical church is frequented by Grace, and whose day job is that of a cleaner. In the first part of this 90-minute drama, much of the humour comes from his spiky relations with his work colleagues, the larger-than-life Abeni and the Eastern European Jovan. As illegal migrants who have escaped imprisonment, their stories counterpoint that of Justice and his sister.

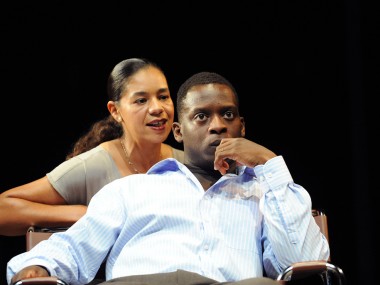

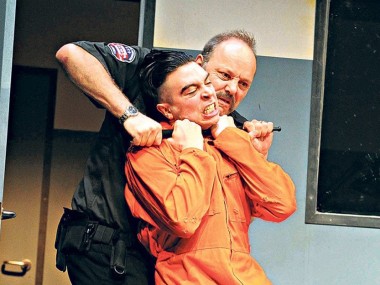

The most original aspect of Agbaje’s play is her account of the relationship between Justice and his sister. At the start, when he is confident of success, they get on fine, and her help is invaluable. Gradually, as his situation deteriorates, so too does their relationship. After two gobsmackingly powerful scenes, during which we witness his abuse at the hands of prison guards and her attempt to use sex to save him, they are practically enemies.

If this is a strong way of showing the human realities of asylum-seeking, Agbaje adds a provocative political point by putting a black Briton into the role of Alfred, the reactionary immigration service jobsworth who insists that Justice should be deported. Yes, the play is both a masterly account of the crosscurrents of racial politics, and a series of crowd-pleasing scenes, such as the one featuring a barnstorming prayer meeting.

But the biggest joy is Agbaje’s language. She writes with a sensitive ear to the multicultural rhythms of London English, distinguishing specifically between black Britons, however educated, and working-class Ghanaians and Nigerians. The result is a vivid picture of the complex panorama of metropolitan life today, and her dialogues are a fine mix of feisty hilarity and grim suffering. This is linguistic diversity, as nimble as a skateboarder and as punchy as a thug.

Indhu Rubasingham’s production, designed by Rosa Maggiora, brings out the best in her cast, with the relationship between Aml Ameen’s Justice and Sharon Duncan-Brewster’s Grace coming across with particular conviction, and with good support from Karl Collins as Mark Cole and Rebecca Scroggs as his gobby sidekick. Jimmy Akingbola gives Alfred a satisfying maliciousness while Kobna Holdbrook-Smith excels as Pra, whose exchanges with Cecilia Noble’s Abeni and Rob Whitelock’s Jovan are a comic highpoint. Detaining Justice is by no means perfect, and it is clear that Agbaje has struggled to give her story a satisfying ending (compare the last scene in the published playtext with that on stage), but it does make a strong case about the need to treat asylum-seekers as human beings through emotionally truthful acting and a passionate concern to give a believable picture of Britain today.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk