Don’t Destroy Me, Arcola Theatre

Monday 15th January 2024

British Theatre abounds in forgotten writers. And in ones whose early work is too rarely revived. One such is Michael Hastings, best known for Tom & Viv, his 1984 biographical drama about TS Eliot and his wife Vivienne, so in theory it’s great to see this playwright’s 1956 debut, Don’t Destroy Me, being revived at the Arcola by director Tricia Thorns’ Two’s Company, whose remit is the discovery and resuscitation of long-ignored work. First staged in the same year as John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, the play is an anguished Jewish family story, but is it any good?

Set in a Brixton flat in 1956, the plot concerns Leo, a middle-aged Hungarian refugee from the Nazis who is widowed and now lives with 29-year-old Shani. While he spends his time getting drunk, she is having an affair with a neighbour, the Cockney book-maker George. When Leo’s 15-year-old son Sammy — who has been looked after by an aunt in Croydon — comes to live with his father and step-mother, his arrival disrupts the uneasy equilibrium of these fraught relationships. Things are not improved by another pair of neighbours, the eccentric and damaged Mrs Pond and her 17-year-old daughter Suki, who live in a surreal fantasy world.

Events revolve around young Sammy’s sense of confusion about who his new parents, old man Leo and young woman Shani, really are and how he can relate to them. Although he finds himself drawn to the other teenager Suki, her complete isolation from the outside world by her over-protective and psychologically disturbed mother means that she is no guide to how to adjust to a new family situation. So when Shani decides to invite the local rabbi to visit, both as a spiritual counsellor and a would-be therapist, Sammy finds he cannot connect to his Jewish heritage. Worse still, Leo arrives in a drunken rage and attacks the rabbi.

Don’t Destroy Me is a sympathetic study in character: Hastings is meticulous in realistically creating a group of believable individuals, each of whom has a distinctive personality. In terms of playwriting, however, the main problem is that Sammy — unlike for example Jimmy in Look Back in Anger — is for most of the play a sulky, inarticulate and troubled teenager with very little to say for himself. Like Suki he is more than a little lost and his chief passion, jazz, is not enough to give him much interest. At least, not for me. To be fair, he does find his voice — in a brief kind of inchoate Angry Young Man rant — at the end of the evening, but by then it’s all too late. Is there a future for him and Suki? For him and his step-mother? For him and his father? Maybe, but who cares? Not me.

So although Hastings has carefully created a small community, including Mrs Miller the landlady, and shows how difficult it is to get any privacy in a building where every flat has an unlocked front door, he really doesn’t have much to say about this Jewish family except for the fact that they are unhappy and that Leo thinks religious belief is just cowardice. Shani’s affair with the loud-mouthed George creates ripples of discomfort and hopelessness, but doesn’t explode the whole situation, and the main plot is often hijacked by the subplot: Mrs Pond and Suki are so strange and verbose that they grab the attention from the other characters.

Despite some good passages of social embarrassment, such as the meal created for the visit of the rabbi, some of the writing drifts very close to that very 1950s vague literary waffle which is frankly both annoying and undramatic. Some of the speeches get a bit rambling, and this family’s tensions simmer, but never seem to boil over. That said, the play is certainly a postwar theatre history curiosity, and its first production at the New Lindsey in August 1956, about three months after the premiere of Look Back in Anger, suggests that we should see Osborne’s play not just as a singular work of creative brilliance, but as part of a more generalized youthful dissatisfaction.

In Sammy, Don’t Destroy Me features a classic 1950s rebel without a cause who, despite his inarticulate moping, symbolises the disaffected mood of teenagers that was to blossom into the 1960s anti-Establishment pop culture. This boy’s cry of “You can’t help me” rings true, but it will be another 10 years before British teens learn to help themselves. In general, however, a lot of promising material — the influence of Jewish culture and the long shadow of the second world war and the Holocaust — is subtly alluded to, rather than explored or discussed. The compensations of dry humour don’t really make up for stunted feel of the drama.

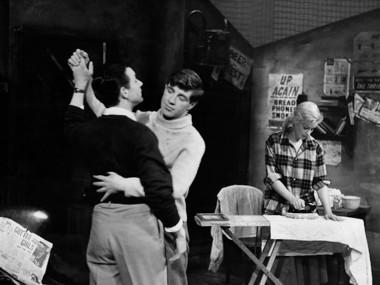

Whatever the shortcomings of Hastings’s play — which after all was first staged when he was 18 years old — it’s hard to fault Tricia Thorns’s meticulous production. The set, designed by Alex Marker, conveys the genteel shabbiness of the Brixton tenement and the performances are very good: making their stage debut, Eddie Boyce is convincingly uneasy as Sammy, given to flashes of anger and with a great line in sulky bewilderment. Equally impressive are Paul Rider’s Leo, Nathalie Barclay’s Shani, Nell Williams’s Suki, Timothy O’Hara’s George and Alix Dunmore’s Mrs Pond. Sue Kelvin gives Mrs Miller some welcome comic touches and Nicholas Day’s rabbi is a study in discomfort. Despite all this excellence the play remains a curiosity rather than a must-see.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk