Endgame, Old Vic

Wednesday 5th February 2020

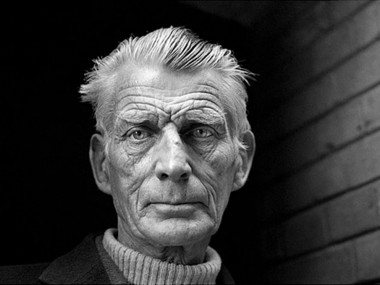

No playwright has had greater influence on successive generations of theatre-makers than Samuel Beckett. Yet it is surprising how rarely his work is revived in the big London theatres, of which this venue is an outstanding example. Perhaps it is a residual fear of modernism, an artistic project which is now more than a century old, but continues to cause anxiety: will audiences understand the work? In this case the question is a good one: Beckett’s Endgame, first staged as Fin De Partie at the Royal Court in 1957 and then translated by Beckett soon after, is notoriously intractable in its meaning. So can a star cast, led by Daniel Radcliffe, Alan Cumming and Jane Horrocks, breathe new life into this modern classic?

Before we can answer this question, the Old Vic welcomes us with a different Beckett play, Rough for Theatre II (c 1960), a rarity which shares the double bill with Endgame. It is a 25-minute music-hall-inspired sketch in which two suits (Cumming and Radcliffe), perhaps bureaucrats, perhaps officials in an afterlife, discuss the possibility of a nameless character, who stands outlined in an open window, committing suicide. His dark silhouette against the white background speaks of both human presence and the absence that follows death. Retelling the story of the man’s life, which is a bare sum of many disappointments, they create a picture of existence devoid of hope.

This double act is well performed: Cumming is like a hysterical functionary, essentially negative and pessimistically painting reality in the darkest of colours, while Radcliffe is milder, more optimistic, more positive. He also throws off his reputation as the world’s most famous wizard by proving to be a precise physical clown. In more than one memorable moment, he manages to leap up onto the ledge while executing a 90 degree turn: it’s both athletic and comic. For the rest of the time, Cumming rattles off the feverish anxieties of office life, fussing about files and an angle-poise lamp, which develops a life of its own. We are in a Kafkaesque wonderland.

It’s an interesting antipasto. Then, after an unnecessary interval, we get to Endgame, the main meal of the evening. The situation in this play, whose title means the final moves of a chess match, is quintessentially Beckettian. Hamm (Cumming), who is both unable to see and unable to stand, lives in complete isolation along with Clov (Radcliffe), his servant, who cannot sit. Outside there is some kind of post-apocalyptic devastation, but inside they survive on routine interactions which are both comic and laced with tragedy. At the same time, Hamm’s parents, Nagg and Nell (Horrocks), live in a pair of dustbins (here metal wheelie bins) which are also on stage.

The theme of the mutual dependence of Hamm and Clov, sealed with the perverse glue of casual cruelty, is a version of the master and slave dynamic found in several Continental classics, such as Jean Genet’s The Maids (1947). Both the superior and the inferior man swap roles so that their identities are constantly shifting, while Hamm’s parents echo their exchanges in an even more surreal key. Added to this, the intimations of an environmental disaster in Beckett’s text — the phrase “no more nature” and the disruption of the sea’s tides —and the fact that the final words in the play are “You remain” cause today’s audiences some amusement about these layers of relevance on top of Beckett’s picture of desperate humans filling a void.

Like any other genuine masterpiece, Endgame changes shades of meaning depending on how often you see it, your time of life, and the nature of the production. For me, now, the piece is both about the void, the bitter humour of survival, and about aging. In the most emotionally real moments, Horrocks and Karl Johnson (Nagg) represent not only Hamm’s parents, but everyone’s family: to those of us who are older, they are also us. If not exactly today, then certainly tomorrow. Likewise, the exasperation that frequently punctuates the relationship between Hamm and Clov feels as if it’s an account of care.

Director Richard Jones and designer Stewart Laing have created a contemporary visual landscape at odds with the traditional Beckettian ambiance of rot and decay. Instead we have a plainness and muted boldness of colour which is almost cartoonish, like pop art caught in the dust of an atomic blast. The set is abstract but simultaneously of today. Some touches are unnecessary: Cumming has exposed prosthetic limbs, feeble and withered. This is a much too literal interpretation. If the tone of the production is deliberately light, there is some good physical humour as well as plenty of dark shadows.

Cumming performs the central role of Hamm with a plummy posh voice which swoops and wavers, with some camp high notes. There is a slight emphasis on the homo-erotic subtext, and the actor pronounces the loaded word “queer” in a purposely exaggerated way. By contrast, Radcliffe is a bit disappointing: although he staggers around, half bent and clambers up and down the metal ladder with several stiff-legged variations, his vocals are weak, and he has little stage presence. Despite this, there are moments of connection between the two men, and the satisfying bleakness of the text is allowed to breathe. This production has many good points, and proves what we have known for a while: that modernism is not longer obscure.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times